Nov 18, 2019 Art

Metro writer Anthony Byrt explores Tuia 250, the controversial commemorations of Cook’s first landing in Aotearoa, and how meaningful change and action comes with engagement with one’s “place”.

On the morning of Saturday 5 October, I stood with my eight-year-old son on Waikanae Beach in Turanganui-a-Kiwa, watching waka hourua and va’a moana — double-hulled Maori and Pacific sailing vessels — arrive in the bay.

It was cloudless, with a sharp nor’wester that would eventually prevent the boats from landing on the beach. Nearby at the port, enormous piles of felled pines were stacked like firewood, waiting to be loaded. A giant cargo ship, the Black Forest , doubly-flagged to China and Hong Kong, was docked there, while two similarly enormous ships hovered on the horizon.

Not far from where we stood, there is a statue of “Young Nick”: pointing out, in a weird reversal, at the headland he had been the first to spot from the Endeavour. Further along is a monument to his boss: James Cook himself, standing on a chamfered globe, compass points at its base. The other Cook statue — the one from Kaiti Hill, which isn’t even a depiction of the man — is languishing in storage at Gisborne’s Tairawhiti Museum: moved there by the local council because activists kept painting his face and balls red.

The arrival of Fa’afaite i te Ao Ma’ohi — which had sailed from Tahiti — and the waka hourua was part of Tuia 250: the controversial commemorations of Cook’s first landing in Aotearoa in 1769.

I was interested in being there not so much for the debate, but for its aesthetics: the physical, visual experience of this strange event. For a while now, I’ve been convinced that, after many years of internationalism dominating New Zealand’s mainstream art conversations, we’re witnessing an important shift towards telling our stories, from our place, here and now, in the South Pacific. Tuia 250, as a visual expression of first contact, was either going to be part of this, or a bizarre anachronism. In the end, I think it’s probably both.

That a shift is occurring seems, to me, unquestionable. Pakeha modernism has recently been in the spotlight, with Colin McCahon’s centenary, a major travelling exhibition of Gordon Walters and his much-debated kowhaiwhai-inspired abstractions, and a Wellington survey of the controversial modernist Theo Schoon, whose engagement with Maori culture was at times seriously dubious, leading to calls for a boycott of the show.

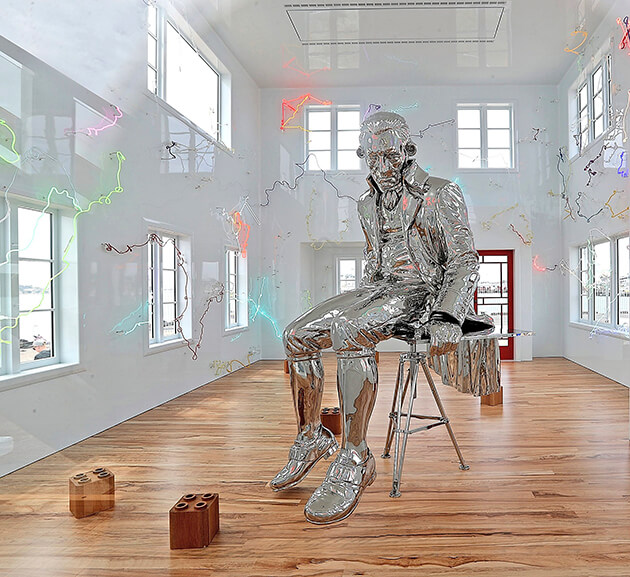

Cook’s legacy is a major part of this too: the Oceania exhibition last year at London’s Royal Academy, which marked 250 years since the departure of the Endeavour from Britain, and included several leading Maori and Pacific contemporary artists (the imperialist undertones of which, at the height of Brexit chest-puffing about Britain’s former splendour as a global power, I’m still deeply ambivalent about); the pensive, stainless-steel captain sitting inside Michael Parekowhai’s The Lighthouse (surrounded by the constellations of the night sky); and, arguably the most popular contemporary New Zealand art work of the past decade, if not ever — Lisa Reihana’s monumental video installation In Pursuit of Venus [infected], based on Cook’s voyages and eventual demise.

Pacific artists have also been instrumental in pressuring the New Zealand art world to shift its view of itself, its sense of place, and its responsibilities. Examples include Kalisolaite ’Uhila’s brilliant performance art; the enormous impact of the LGBTQI+ collective FAFSWAG; Edith Amituanai’s photography; Janet Lilo’s installations; Christina Pataiali’i’s paintings; and Lemi Ponifasio’s incredible choreography on the world stage. This year, Yuki Kihara was chosen to be New Zealand’s official representative at the 2021 Venice Biennale (disclaimer: I was on the selection panel) — the first Pacific artist to be given the opportunity.

In a recent, critical review of Te Tuhi’s exhibition Moana Don’t Cry, Lana Lopesi wrote of this new curatorial and artistic enthusiasm for Pacific narratives that “the cynic in me thinks that just as the Pacific was the last place to be colonised, it seems too that the Pacific is the last of the ‘exotic’ foreign cultures, ready to be used for its conceptual promise…” She may be right. But I think there’s something else at play here too, which reaches beyond the art world’s constant and voracious need for newness. There is a widening sense, which began in 2016 with the shock of Donald Trump’s election and has been accelerated by the climate crisis, that it’s no longer acceptable to blithely participate in the international art world’s oft-depoliticised puff and pageantry, while the rest of the planet burns (or, in the case of South Pacific nations, sinks under water). Meaningful change, and action, can only really come through specificity: through an understanding of, and engagement with, one’s “place”.

Tairawhiti Museum has offered a brilliant expression of this with the exhibition Tu te Whaihanga, which opened during Tuia 250’s first days, and includes 37 taonga from British museums that left Aotearoa on Cook’s expeditions. These include: a rare kahu kuri (dog-skin cloak); painted hoe (waka paddles); an amazing rei-puta (whaletooth necklace); taiaha and a range of patu.

The exhibition’s great strength is it doesn’t treat them either as “art works” in the Western sense, or as anthropological displays. Instead, they’re treated as taonga, their mana and meaning inextricably linked to their connections to real people and real bodies; and to their subsequent lives, first on the Endeavour and then far from home.

These connections are emphasised by extensive wall-texts about the miscommunications and murders, as well as the successful exchanges, of those first days of contact 250 years ago.

These living presences stood in stark contrast to the strange arrival on the morning of 8 October. My son and I stood in roughly the same spot as we had a few days before as we watched the replica of an 18th-century barque, accompanied by other tall ships and a naval vessel, sail into the bay.

This was surely the weirdest part of Tuia 250: that the British side of the first-contact equation was represented not by a contemporary expression of a living culture, but by a facsimile of the Endeavour, first launched in 1993. As it lumbered into port, protesters were there to meet it, waving Tino Rangatiratanga and United Tribes flags. The protest, in truth, was pretty small; but so too was any enthusiasm for the Endeavour’s arrival.

The Endeavour replica, and its presence in our waters, is a failure of imagination. It is out of place, and time, and as an object, doesn’t know where it really wants to be. The waka hourua and Fa’afaite, which had sailed in ahead of it, were the total opposite. These were distinctly 21st-century boats: remarkable things built around the foundational principles of long-distance Pacific navigation — not the magnetic points cast in concrete under the Cook statue’s elevated feet, but the sophisticated system of constellation recognition that enabled Pacific sailors to populate their ocean by following the stars.

As one crew member explained it to me, the compass Pacific navigators use is not an object; their compass is their own bodies.

The system is based, fundamentally, on a constant understanding of place: of knowing exactly where you are, always in relation. This seemed a useful metaphor for how we understand an emergent change in Aotearoa’s contemporary visual culture. And, for me at least, it contributed to a new clarity about what we should be asking of our art, and where we find the stories that really matter.

This piece originally appeared in the November-December 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Replicas and revelations”.