Jul 22, 2025 People

Whether abstract painting is ‘citational’ — say, if it points to canon, if it has painterly forebears — does not help to determine its quality or value. Rather, the figuration itself, the bursts of colour and form within the picture plane, are an inflection point from which nothing becomes something. It’s a collaborative effort between artist and viewer, so long as the viewer is sufficiently hooked (perhaps by a flaring colour, a reminiscent daub) and eager to respond to or decipher a painting (in any way they see fit).

Abstract works can ask that our shared reality of objects and legible forms be suspended for what is usually a nocturnal activity — that nightly alchemy whereby experience and time are disassembled in a vat of REM-acid, in which currents allergic to analysis are given free rein for a cycle of orgiastic associationism. Auckland-born, Los Angeles-based Emma McIntyre’s output as an abstract artist is most closely aligned to these traditions, despite her will to skirt and expand what being ‘abstract’ even means.

For example, in An echo, a stain — a 2023 showing at David Zwirner gallery in New York — McIntyre exhibited paintings (massive ones) bristling with vibrant detail and belligerent movement. Belligerent, because the ratio between colour and figure seemed fraught, as if the works themselves were an effort to capture the tension between the eye and the body, between the conceptual processing of an image and the body’s digestion thereof. Because we do eat images — they sit in the body and tug at our nervous systems, as anyone who has seen a French film made in the late 2000s will tell you (which isn’t even to mention the body-hogging ways that traumatic memory, or memory itself, sits in the bones).

With titles from McIntyre like Queen of the air, Duet in the dust and Laws of night and honey, it’s not a stretch to call her painting experiential. The works point to the sensations of living, the way moments form like weather, generated by certain conditions and people or objects in vital but fleeting tension. For the same New York show, and perhaps describing her practice at large, McIntyre cited Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Cy Twombly, Pierre Bonnard and Jean-Antoine Watteau as influences. And yet these references did not crowd the works’ feeling of sparkling activity (like elemental fibres refracted under a microscope), nor stymie their uncanny capturing of realities that exist between our usual visual markers.

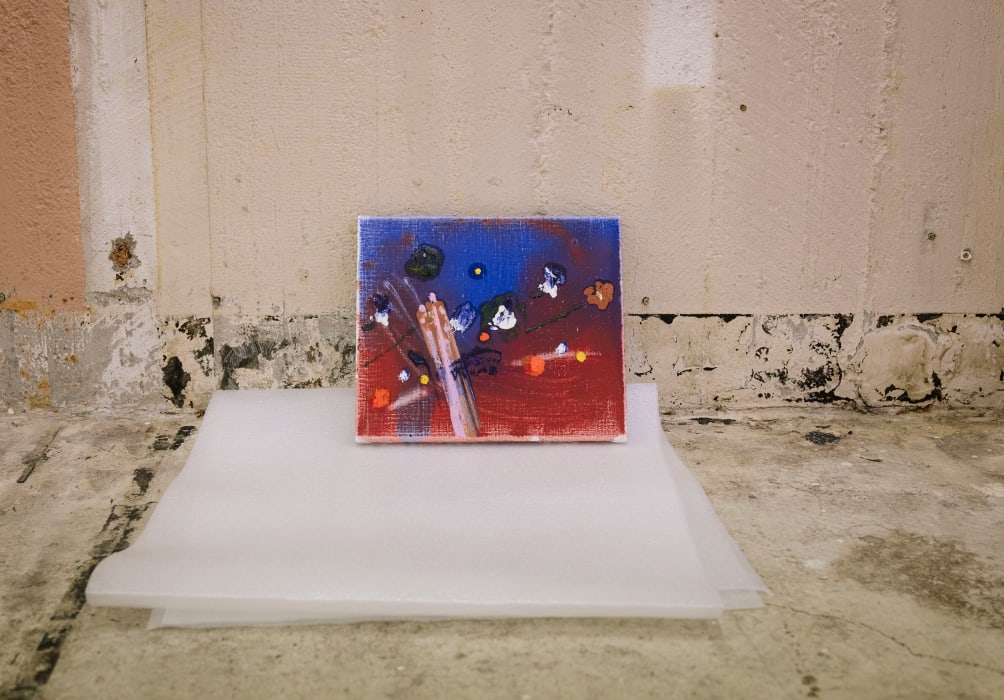

Emma McIntyre, Sweetly gently, 2024

Still, it may be impossible to be any sort of painter these days and not have parallels drawn to existing styles and art historical figures. Which is simply an artist’s engagement with canon. As in any other sphere, you access and refine a skill only by wading out to meet the masters. McIntyre’s work, perhaps her real discipline, seems bent on interrogating the question, ‘What does it mean to paint in the abstract tradition?’ Certainly, the subject of abstract artists is still the world, life itself — though an artist who paints objects and scenarios legible to the eye happily signposts their inspirations, while abstractionists and other modernists demolish their subjects in favour of energetic-hermetic expressions. I guess you could liken it to molecular gastronomy, the culinary practice of disassembling and resynthesising foods into novel components that the eye doesn’t recognise but the senses still covet. Such results may be strange and unappetising on paper, but in the eating (more often than not) completely fucking delicious.

Like molecular gastronomy, Emma McIntyre’s rise as an internationally successful artist has been unexpected, and unexpectedly delighting. Not because the work itself doesn’t warrant it, but because such trajectories aren’t exactly common for New Zealand artists. Though success in Europe is not unheard of, it’s much harder to crack the American market. And yet McIntyre, who graduated with an MFA from Elam School of Fine Arts in 2016 and another from ArtCenter College of Design in California in 2021, currently has both in her wheelhouse. She’s represented on the two continents by gallerists fully aware of her appeal — in addition to David Zwirner, she shows with Château Shatto in LA and Air de Paris in, well, Paris — and, with the taste-making confidence of insider traders, they’re offering her work to a public that can’t seem to get enough. Keep in mind ‘public’ is a generous word when describing the art world; it is in fact more akin to a sealed chamber whereby even qualitatively massive successes can be invisible, camouflaged by the scene’s insular byways and judgements that don’t often cross the threshold to the general public.

You might not think that was the case, however, if you measured things by the public turnout for Objects or Vapours, McIntyre’s October 2024 show with Coastal Signs. Unassumingly parked between high-rise apartments and intermittently used offices on Anzac Ave, Coastal Signs has been McIntyre’s representation here at home since she helped form this co-operatively owned gallery in 2021. And so the show was part of a circular moment for McIntyre, a bookend to her Covid-spanning rise from local to global artist — and something Coastal Signs clearly wanted to mark differently. Rather than exhibiting the painter’s new works in its regular space, the gallery rented an empty building a few doors down, an otherwise abandoned and visibly neglected office which, counterintuitively, curatorial choices left in an interesting state of dereliction. This turned out to be productive and lucrative for both gallerist and artist, as the lure of a touted local artist showing new work in a decayed, Kafka-haunted building drew many viewers and purchasers. This audience was way beyond the art world’s usual headcount; and the prices, not listed on documentation, were quoted in US$ and far from guaranteed — interested parties put their name on a waitlist and hoped for the best.

Emma McIntyre, Lake of fire, 2024

Emma McIntyre, Vair, 2024

Emma McIntyre, Vair, 2024

As the title of the show might suggest, these paintings continued McIntyre’s compositional experiments into what’s possible in the visual registers of abstraction — preconditioned by her references (obviously), but working hard to launch into their own expansive mysteries. Beyond gesture and floating refrain, figures did emerge, like the heron in Demi-paradise (2024), an enormous floor-to-ceiling oil on canvas reminiscent of a watercolour but demolished, drowned in negative space. The painting was not immune to the customary uses of the palette suggested by that title, however; McIntyre’s stately heron could be said to place a viewer in a garden, pondside, replete with greenish scums and bobbing reeds. A pair of more perfectly rendered roses were a tell.

Then you had smaller works that showed just how scaleable the artist’s practice is, as her ideas migrated across sizes with ease (something that is not broadly achievable, I might add). These more modest-scaled works were more densely packed, though without overcrowding. They showed the artist’s reverence for her movements — never cajoling the forms into forced company, always haloing them with enough oxygen. You got a sense of their completeness.

Finally, there were works like Incantation (2024), another huge floor-to-ceiling canvas. Only here the artist’s oils were joined by a gorgeously rust-coloured block of iron oxide, a reddish-brown colour that made its residues of yellow and blue starker. More frenetic, like meteorological movements over an earthen surface. Water and sunlight playing on molten pewter. A scrubby patch of earth with a few jolly flowering weeds.

Arguably, the novelty of Objects or Vapours was that its charming dishevelment (meaning the show’s location) offered meta-commentary on what it’s like being an artist in New Zealand. First, the country’s geographical isolation, its distance from major works kept in galleries and museums in larger metropoles, and which aspirants down under are forced to covet between the pages of books. It’s like being in a religion but never actually getting to go to temple. Or else being haunted by the constant reminder of ‘elsewhere’, as if our country were itself the dilapidated ruin and McIntyre’s work a glimpse of that evergreen, out-of-reach promise. The sense that we’re separate from the real action, from the flux of ideas and creative bursts that underlie a broader canon of art history, and that New Zealand is somehow culturally and spiritually impoverished compared to our mother and father countries, is a familiar one. But also, of course, delusional.

Besides, the world is incredibly networked now. The attainment of international glory in any discipline falls squarely on the chutzpah of the practitioner, though there are certain key ingredients you need, like talent and stamina (and the occult conditions of timely exposure) — and none of this precludes the fact that we have homegrown contemporaries to rival any overseas. But Emma McIntyre, remarkably, has struck the climactic theorem of success in a world given to elite gatekeeping and academic jousts. The criteria for such things is, like her own panels, frequently opaque. As she’s proven, however, such opacity is not incompatible with an exhilaratingly authentic practice.