Jul 24, 2025 People

Sometime in the 1980s, a massive fire ripped through the home of sculptor Greer Twiss, destroying around 60% of his accumulated artwork, including many of the intricate, handmade puppets that he had made and used in his career. Twiss, with his usual wryness, took it in stride. “It was a good way to clean house.”

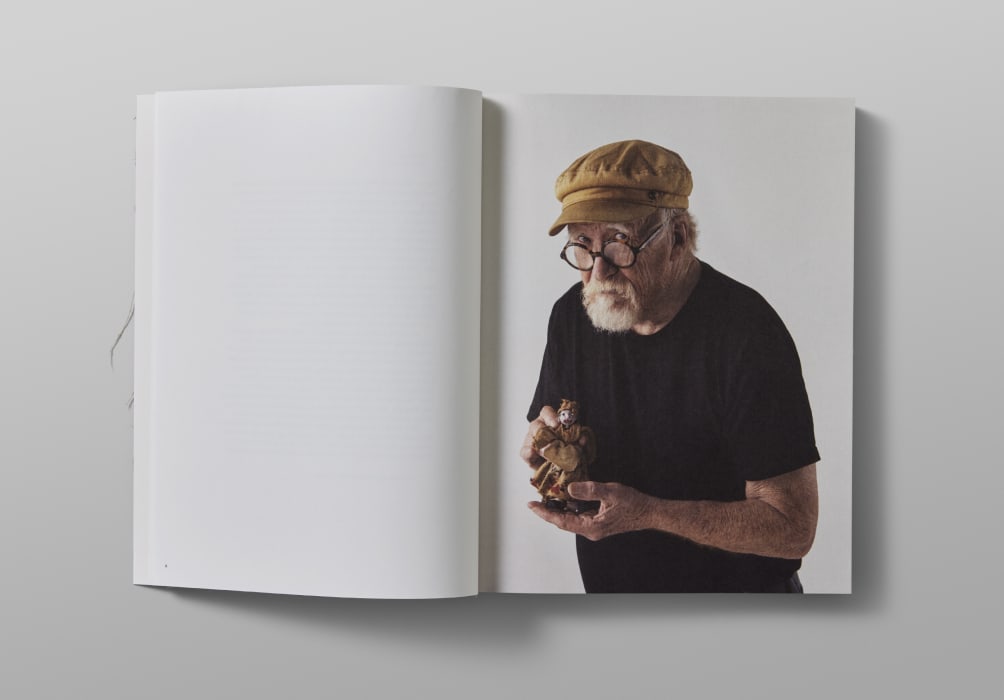

The home Twiss, 87, and his wife, Dee, now occupy sits inconspicuously amid the hustle and bustle of Ponsonby, tucked between cafes and offices. Inside are two floors: above, the living quarters, with a newly installed lift to transport the two up and down as needed; below, a sprawling studio space, which is sometimes hired out to local practitioners. As one might expect of one of the foremost New Zealand artists of his time, it is jam-packed with the flotsam and jetsam of a creative life. There is nary an inch of space left uncovered; the walls are crammed with work by Twiss himself and by many, many other artists. Shelves and cabinets are lined with curiosities — statues, sculptures, bits and bobs.

For a long time after the fire, Twiss had a small assembly of his most beloved remaining puppets hanging in a corner of his workshop. One day, the rack holding them fell, and the puppets were smashed. As he was repairing them, Twiss suddenly got the inspiration to unearth the other puppets that had survived the fire, which he’d stored away.

Greer Twiss, Crocodile

Greer Twiss, Crocodile

“I pulled them out and started to hang them on the wall,” Twiss says. “I had about 30. And Dean Poole, who is an ex-student of mine who runs a design firm, and for some reason seems to delight in publicising my exploits, came over and said, ‘Oh, there’s a book here.’” The resulting book, Greer Twiss: Puppeteer, released by Poole’s company Alt Group, is an astonishing compilation of images, capturing Twiss’s remarkable puppets in a way that evokes their patchwork beauty.

“Greer was my professor and had been part of my life for many years,” says Poole. “His son Toby and I were friends in art school, and I graduated studying sculpture with Greer.” He became more familiar with the puppets as he grew closer to the family. “The puppets always turned up at certain family occasions, whether that be weddings or children’s birthday parties. We quickly realised they were a key part of who he was as a creative, but they were also kind of separated from his sculpture practice. He said that he was restringing the puppets, so I suggested we photograph them all, and that turned into the book.”

In making the book, it became clear that while sculpture is the form for which Twiss is most revered, it had all started with puppetry. That was Twiss’s first love as a child in 1940s New Zealand.

“I’m still a puppeteer in part,” Twiss explains. “Sculpture has a sort of quality that’s similar. I like making little people. I still will pick up a puppet and come in here and put on music and perform. I’m a song and dance man at heart — if only I could sing and dance. It’s my instrument.”

Spread from Greer Twiss: Puppeteer, 2024. Published by Alt Group

As a young asthmatic, unable to take part in sports, with a shock of red hair, Twiss was required to find other forms of entertainment. “[My puppets] were always illustrations of music that I found. I collected records — 78s, mostly from Marbecks in Queens Arcade. I had a big table at my parents’ house in Epsom. At the back of the house was a maid’s room, which was my little working room. I had a huge table that my grandfather had built. It was a split table and I’d slip down the middle and put puppets up through the hole. I’d put them on pegs or on sticks at that time. And I’d lie under the table and play the record with my gramophone and poke them up.”

The first image in Greer Twiss: Puppeteer is of one of these original puppets, a delicate little dancer in a floral dress. Already, Twiss had established his particular style and approach — his puppets performed to music, and ‘spoke’ for Twiss, who never showed his face or made a sound. “I avoided ever uttering a word. I hid behind them completely. Behind the screen.” As I interview Twiss all these years later, the way he talks about that era conjures the spirit of the shy little boy. There’s a delicacy to him that is as intriguing as it is endearing.

Twiss’s career, he makes plain, is the result of having supportive and encouraging older people around him, both family members and teachers — an enduring reminder of the importance and value of fostering young artists. His parents’ deep love of creating things was foundational: “I was an only child and my father was a great carpenter and engineer. He could build anything. My mother was a seamstress. She’d been a buyer for Farmers. She was involved in the arts in a peripheral way and he was involved in building things. He had a great workshop. If I needed a piano for a show, he’d make one for me.”

As Twiss got older, certain teachers encouraged his craft as well, with one as early as primary school suggesting he think about attending art school in London one day. At the same time, the puppets were becoming more complex and technically intricate. By the time Twiss was at Auckland Grammar School, he considered puppeteering as his main pursuit. “I thought that was what my life would be like — I’d be a puppeteer.

Greer Twiss, Pianist

Greer Twiss, Pianist

“They didn’t know quite what to do with me [at Grammar]. I was a sickly little child. But luckily I had a headmaster who had his eyes open and could appreciate things other than sport.” The headmaster’s suggestion? A puppet club. “He decided the best thing to do was to put me up in the top tower in one of those turrets. He realised I had some talent elsewhere. There were about six of us. We had a great old time.”

It was during this time that Twiss became something of a fixture around Auckland — he was “the puppeteer”, featured regularly in newspapers, performing shows at parties, charity events and in the children’s department of Smith & Caughey’s. “Suddenly, it became more professional.”

Listening to Twiss, one realises that much of his life is a window into the past of this country — the people he met and the places at which he performed. One of the most historically significant sites wasn’t a physical stage, but the screen. On 1 June 1960, at 7.30pm, the first-ever television broadcast in Aotearoa played for a little over three hours. Featured were the Howard Morrison Quartet, a visiting ballerina, an episode of The Adventures of Robin Hood, and a puppet show by Greer Twiss. One of Twiss’s most beloved creations, Sadsack the Clown, played the violin and tapped his toe along to the music.

“I don’t know how it came about,” Twiss says. “Television had something of a history with puppeteering in England, and the people who ran television here were mostly second-rate producers from Britain. When I got on TV, the puppets got more sophisticated. They didn’t have rights to the pop music I was using, so I asked to crack into the archives.” Twiss uncovered a treasure trove of archival old-timey musical tapes, which set the tone for one of the most popular regular broadcasts in the early days of New Zealand television. “I’d make a musical of puppets, an old-time musical playhouse. Came on once a week. I wouldn’t be on screen, of course.”

Greer Twiss the touring puppeteer was a personality at this point, even as the money failed to flow. A Twiss puppet show was an expected thing at major community events, and a family affair for Twiss and his parents. From the Auckland Easter Show to tiny community halls in the regions, the three Twisses brought a constantly evolving troupe of puppets and sets to the people. “My parents got more and more involved. My father loved making little sets and props and things. My mother loved to make dresses. We used to have endless arguments about it — I was a real prick of a child in a lot of ways. I knew what I wanted!” he laughs.

He recalls a puppeteer named Arnold Goodwin, whom he encountered early in his journey. “He did Shakespeare plays with puppets. I met him when he was in his 70s or 80s and I was starting puppeteering. And he said, ‘My boy, don’t have anything to do with puppets. All you’ll end up doing is children’s birthday parties.’ And he was quite right — that was the inevitability in those days. I did birthdays a lot — I still run into people who say, ‘Oh, you did my birthday.’”

I ask if Twiss has a favourite creation. “I have puppets that I really love, because they work themselves. Something clicks and whatever you do with the puppet works. It’s a nice feeling when it all goes right.”

For Poole, there is only one answer. “My favourite is Sadsack the Clown. That’s the one we open the book with. His violin is highly performative, and for a marionette, you’re using gravity in a certain way and you’re articulating these puppets to mimic the human form, but this one has a special string connected to a toe and the toe taps away to the music. It’s a bit like kabuki theatre. It’s a technical feat but it’s also very humorous.”

At art school, Twiss found a new muse: sculpture. It was not so far removed from puppetry, but the performance element receded, giving way to what became the most influential portion of Twiss’s career — large-scale sculptural work in cast bronze, galvanised iron and fibreglass. He became well known for figurative forms with wry inversions and strident dynamism, which was summarily recognised in 2011 when he received an Icon Award from the Arts Foundation. The two modes “flowed into one another”, Twiss says. “But I virtually gave up puppetry when I got to art school.” Instead, he felt an urge to push the boundaries he had set for himself. “I felt I could break more rules with sculpture. I was hooked into a style with the puppets — playing a record with realistic-looking puppets. They seemed restrictive.

“I could’ve gone on a Dada trip with them — that would’ve been interesting — but I didn’t even know about Dada at that point.”

The puppets had the sheen of a childhood passion, rather than an artistic practice. This judgement was underscored by the traditionalists at art school. “That was kind of the training you got. They were more interested in life modelling and sculpting from antique casts. Not much inventiveness going on. It was pretty restrictive.” Nevertheless, Twiss emerged with an astonishing ability to mirror and subvert the world around him in a way that made a deep impact on the New Zealand art scene — and aspects of his puppets persist within. Twiss likes to talk about “ad hoc-ism”, his own definition of his artistic style, in which he embraces and accentuates a work’s flaws, bumps and hollows. His sculpture — and his puppets — reflect the man himself: a little odd, a bit idiosyncratic, possessed of multitudes.

In later life, Twiss’s puppets appeared only occasionally, usually at private functions. The artist’s other great role in life has been as a teacher, at Elam School of Fine Arts but also at St Cuthbert’s College, which is where I got to know him while making a series on artists who had made significant contributions to the school. “He’s a living icon, not just one of our most important artists but our most important art educators, too,” Poole explains. “He taught us all. Niki Caro, Michael Parekōwhai, the list goes on.” For certain members of the Elam staff, Twiss bestowed a particular honour — a puppet of themselves, introduced at their farewell party.

“I did start to make puppets on specific occasions for people. I think the first was for Sebastian Black, who was a lecturer in the English department [at the University of Auckland]. He was terribly English,” Twiss says. “Sebastian wore shirts — Liberty shirts. I thought, ‘I could make a puppet out of him.’ I had his wife give me 20 of his Liberty shirts, which I knew would horrify him. And I had the puppet hurl shirts into the crowd.”

Twiss, something of a wallflower in life, enjoyed his puppets’ diabolical streak. “I could see the effect it had. You could do all sorts — bop them on the nose or whatever. It was great fun. Historically, puppets got used a lot politically. You could say things and go, ‘It wasn’t me — it was the puppet.’ So I started making a bunch of these hand puppets, which I could use to go up to people and cause mischief. It was the first time I’d broken out from behind the stage. Someone said one day I’ll do away with the puppets entirely and really come out.”

One of the most infamous incidents was at the wedding of Twiss’s son Jacob. “I made a puppet of Jacob and a puppet of [his fiancée] Lindsay. I found a great record — Kris Kristofferson or someone. And it’s really obscene. The puppets sang to one another.” It was a moment that would live in infamy in the Twiss family.

“Lindsay’s family is fairly upright,” Twiss says, scratching his chin bemusedly. “They were horrified. There were a few people at the wedding who felt it was a little over the top.”

The puppets don’t really make public appearances any more. Every now and then, Twiss will pull one out and play with it for old times’ sake. He shows me a favourite of his — Sassy, a red-haired vixen, clad in a crimson dress. Outside of, perhaps, The Muppets, puppets don’t necessarily have a huge cultural cachet these days. It’s a shame. There’s an uncanny humanity to Twiss’s creations that comes from the fact that they are extensions of himself, a means for him to interact with the world. I wonder if it is protection or liberation he seeks in substituting his own persona for the ones with which he inhabits his puppets. I suspect the answer to that is as much a mystery to Twiss as to the rest of us. It makes the serendipitous tumble of Twiss’s puppet rack, the production of the book and its final printed form all the more precious.

“There were a bunch of ex-students of mine [at the puppet shoot]. We got up on this platform with the puppets and [the photographer], who does a lot of fashion photography, he’d come up and brush the hair of the puppets, clip the hair where it was sticking out badly. It took two days — it was great fun.” It was a somewhat surreal experience, these esoteric items of the past being brought to life one by one, immortalised in a slick photography studio. “It was really lovely to see them being cared for in that way. I had pushed them aside, thinking I’d do something with them one day — donate them to the museum or something.”

Poole says those assembled recognised the rarity of what was being captured. “Greer would pull out one puppet, bring it to life, and we’d document it. It was a two-day private performance where he’d bring these characters to life.”

The last puppet Twiss shows me is one he made of wife Dee for her 80th birthday. It’s a beautiful thing. I suggest to him that I imagine he’d only go to the effort of making a puppet for someone incredibly special.

“Oh, yes,” he concurs. “Oh, yes.”

–

Images in this story are courtesy of Alt Group