Jul 29, 2025 People

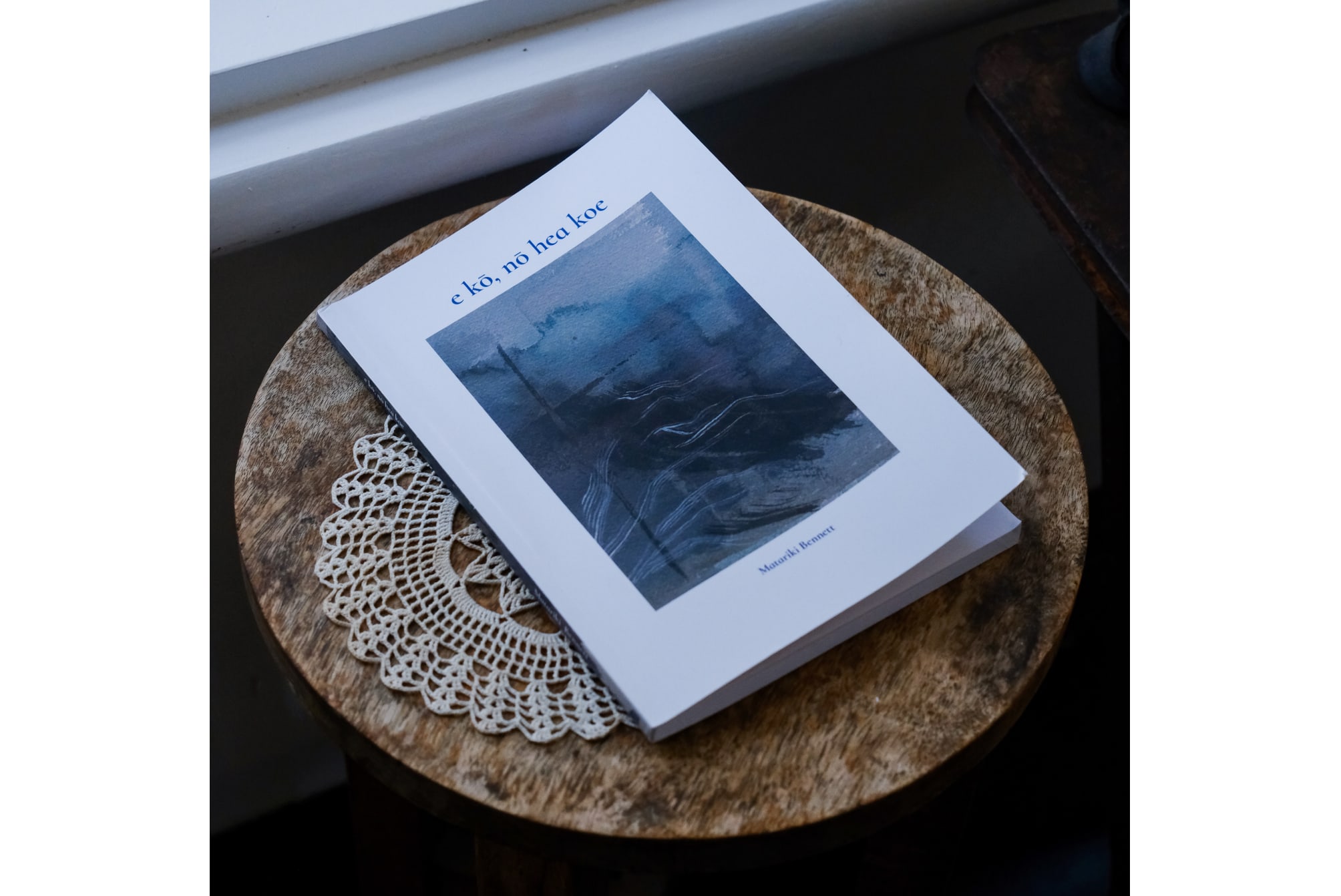

In her debut poetry collection, e kō, nō hea koe (‘girl, where are you from?’), Matariki Bennett seamlessly navigates the realms of whakapapa, memory, grief and environmental imagination. It’s a coming-of-age exploration of identity, weaving intergenerational dialogue, cosmic visions and the quiet strength of silence into a deeply personal yet expansive work.

Metro caught up with Bennett (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Whakaue) to kōrero about the threads that connect her creative practices, the role of whakapapa in her storytelling, and how poetry serves as a vessel for mourning and transformation.

Metro: You work across poetry, film and curation. How do these practices feed into each other?

Matariki Bennett: My whole whānau are artists — across all kinds of mediums — and I think just to survive, you kind of have to stretch yourself. Like, to make a living and keep going.

[Bennett’s father, Michael Bennett, is a writer and director, and her mother, Jane Holland, a costume designer, artist and writer.]

With film, I love writing and directing, but the work that sustains me is costume. There’s more regular mahi in that space. But costume has taught me heaps — it’s still storytelling, just from a different place. You’re working closely with actors, thinking about how a character comes across, how their world is built. There’s so much story in how people dress and move. That definitely feeds back into how I write and direct — being able to hold the whole arc of a film emotionally and visually.

Poetry is more immediate. Writing for film is slow and collaborative, whereas poetry is something I can return to in the moment — it lets me process something right then and there. That quickness nourishes everything else. And curation is the space where I can uplift other artists, bring together different voices, make connections. They all kind of talk to each other. Nothing sits in isolation.

Which medium did you begin with? Was there one you naturally gravitated toward?

Poetry’s always been the one. I’ve been writing since I was little — I always thought I’d write a novel one day. When I was 12, my parents enrolled me in the Gotham Writers Workshop, an online school based in New York. It felt buzzy, being in Aotearoa while everyone else was in the US. At first, I wrote short stories. But when I was about 14, I was in a class with my friend Manaia — she’s Hone Tuwhare’s great-granddaughter — and we came across a Rudy Francisco spoken-word video on Facebook. We were, like, jaws on the floor — What is this?! We knew straight away: this is what we want to do.

Our teacher, Whaea Alice, made it happen. She connected us with Action Education, who run poetry slam workshops across Tāmaki Makaurau. That space changed everything for me. It’s technically a competition, but really it’s about listening, finding your voice and being heard. Spoken word became the form where I felt most comfortable — it just clicked. That performance element felt really natural to me, and it still does.

What does a good day of making or curating look like for you?

When I was working on the book, I didn’t want to force anything. It’s easy to get stuck in the pressure of deadlines, but I tried to treat the process gently. For me, writing always begins with reading, taking in other people’s work, listening to music, watching films, going deep into research. All of that builds the writing.

I made playlists for each section of the book — just mood-setters — and my sister, who painted the artworks, would listen to them while she painted. I also made mood boards with photos of people, places, time periods — especially for the more political pieces. I’d do deep dives into the history and context before I even thought about the poems.

These days, a good day starts with a walk. Living on the south coast of Pōneke, being right next to the moana, helps clear my head. Then I’ll come home, put on music — something without lyrics I know too well — and start piecing ideas together. I keep one-liners and fragments in my notes. Sometimes a line from weeks ago sparks something new. It’s all about stitching things together.

I try not to put pressure on outcomes. Even just showing up, reading, brainstorming — that’s enough. Poems shift as you shift. A good day is just one where I make space to be with the work.

Has your relationship to storytelling changed as you’ve moved between forms?

Definitely. Writing fiction or screenplays takes a different kind of stamina. It’s long-form — you sit with characters for a long time. You’re mapping out their arcs and the arc of the whole story. It takes planning. Often those characters aren’t you, even if they’re inspired by people you know.

Poetry is the opposite. None of it is fiction — it’s all true. It comes from my life or the lives of those close to me. I’m not inventing a world; I’m distilling real moments. It’s about asking, “What’s my relationship to this? Do I have the right to speak to it?” That personal connection is everything.

When I was writing the book, I’d meet with my mentor Ken Arkind, who I’ve worked with since I was 14. He’d ask, “What does this line mean to you?”, and we’d unpack it — maybe it linked to a memory, a person, a place. Nothing I write is empty. Every word has weight. And in poetry, there’s not much space — you’ve got to make each line count.

Your debut collection, e kō, nō hea koe, feels deeply personal but also looks outward — towards whenua, whakapapa and the future. What grounded you while writing it?

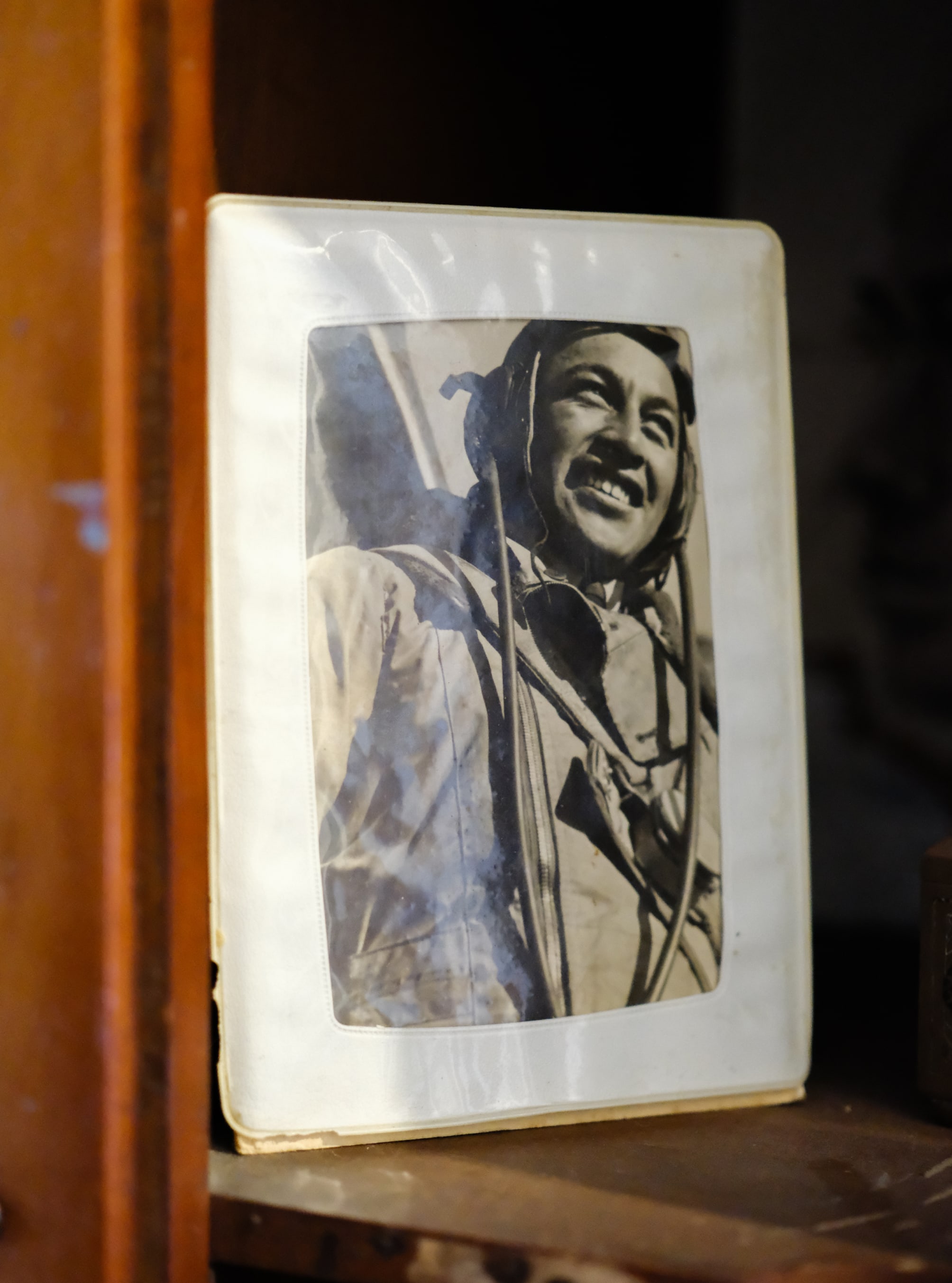

When I started the research phase, I didn’t expect to find what I did. I spent a lot of time in the sound archives. I typed in “Bennett” and found recordings of my grandfather — who I never met — speaking on the radio. I also found my great-uncles and my great-grandfather [Frederick Bennett], who was the first Bishop of Aotearoa. Hearing his voice in te reo Māori — it was the first time I’d heard anyone in my direct family speak the language fluently. My dad and grandfather didn’t. Being in the sound archives felt like meeting them for the first time.

My grandmother, my mum’s mum, was another anchor. She’s a constant presence in the book. She lives in Ōtaki, and I visit her as often as I can. We have these long conversations about the universe, poetry, everything. She was a teacher — language is everything to her. I asked her for her favourite poems, and my grandfather’s, too. They became part of my research and inspiration.

I even included the bones of poems I wrote when I was 14, adding my current voice and perspectives to old ideas. Reworking these poems helped me reconnect with my younger self.

Whānau, whakapapa, whenua — those are what grounded me. Those threads run through the whole book.

You describe the poems as “a series of goodbyes”. Was writing the book a way of holding on to something, or letting it go?

I think it was both. When you move through your teens into your twenties, there’s so much change. You’re letting go of people, places and ideas about yourself. I’d just moved to Pōneke when I started writing this, so everything was new — new city, new challenges, new relationships. A lot of it was about letting go of friendships, or spaces that held memories I had to leave behind.

Writing helped me work through those transitions. It was definitely therapeutic. Some days I’d end up crying at my desk — not in a sad way, just deeply moved. That’s part of grief. You go through those stages so you can reach a place where you’re ready to share it with others. Letting go can be painful, but it’s necessary to grow.

The book is really personal — it’s a snapshot of a specific time in my life. I hope people can see parts of themselves in it, or find some sense of healing through it. It’s about learning to let go, and trusting that things will be okay on the other side.

The visual language of the book has always felt just as important as the words. My mum’s paintings are on the cover — she’s painted my whole life, and her work has always been around me. She also wrote a [Master of Creative Writing] thesis years ago called Eulogy, and I remember her reading parts of it to me when I was little. That book, and her art, stayed with me as I wrote mine.

Originally, my sister had created a painting for the cover. But later, I asked Mum if we could use one of her Motherlines paintings instead. It just made sense. That painting became the cover, and my sister’s work now appears throughout the book’s pages. To me, it feels like the book itself is our mum — holding both me and my sister within it. That motherline connection runs all the way through.

What matters most to you when creating exhibitions or spaces, especially for Māori and Indigenous artists?

It’s about platforming the right people — the ones who deserve to be seen. My dad and I worked on curating for the Auckland Writers Festival, and we tried to broaden the idea of what it means to be a writer. We opened it up to songwriters, whose work might not be in a book but is still equally as powerful. Spoken-word poets often get overlooked because they don’t have a print collection, but their craft deserves a place. Same with actors and filmmakers — their storytelling is real and meaningful, even if it’s not in a ‘literary’ space.

I’ve grown up surrounded by amazing artists. All I’ve ever wanted is to bring the best writers I know into one space and let them share their most powerful work. It’s about creating space where everyone feels seen and strengthened by each other’s art.

e kō, nō hea koe, by Matariki Bennett, is published by Dead Bird Books, $35.