Nov 18, 2015 Art

The disturbing aesthetic of Chinese artist Yang Fudong.

This article was first published in the November 2015 issue of Metro. Main image: Yeijang/The Nightman Cometh, 2011.

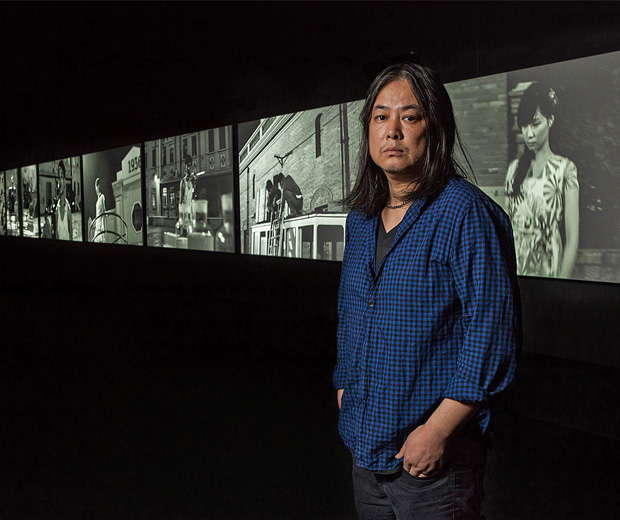

He’s quiet, a man of small, careful movements, with a fleshy face and what used to be called a comfortable weight around the middle. Dressed in black, soft shoes, shirt loose, long straight grey-streaked hair parted in the middle and hanging like a curtain across the back of his neck.

He looks wary, as if he might need to walk away at any moment, except he is also one of the most acclaimed contemporary artists in China, and the reason he’s here is to be an honoured guest of the Auckland Art Gallery. He’s among fans, but it hasn’t made him relaxed.

Yang Fudong is a moving-image artist. His subject is the modern world, although he comes at it obliquely, with works that evoke history and myth, rural isolation and a cinematic nostalgia: images of people and places ring true from movies rather than real life. A warrior and his horse in the snow; a town square in the evening; women frolicking at the beach.

In black and white and, more recently, in colour, his works have an extraordinary luminous intensity and such beauty that it feels close to aesthetic perfection. And yet there’s a troubling power in them, too. They’re like dreams, with mixed-up realities, events that repeat and situations that cannot be quite as they seem. It’s as if the imagery is capable at any moment of collapsing into something very different.

With beauty like this, danger waits in the wings.

Filmscapes, showing now at the gallery, includes three works. In the first room is Yejiang/The Nightman Cometh (2011), which features three incongruous but interlocking sequences in the snow, with a warrior from a time long past, a young contemporary couple, and a woman in traditional dress from an indeterminate period. It’s freighted with Chinese symbolism, obviously, not the least of which involves powerful animals — a deer, a horse, a hawk.

In the second room is 2010’s The Fifth Night, presented on seven screens arranged in a flat arc so you can watch them simultaneously. It’s a pastiche of a scene from a noir movie, with all the screens showing different aspects of a town square in a single time sequence, but the angles are such that nothing quite matches up, including the sound — you can work out some of what’s going on, but not everything. It’s like everyone is waiting for something immense, or maybe it’s just life and they’re not… and it’s awfully hard to stop looking.

The third work is new, commissioned by the gallery and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne. The Coloured Sky: New Women II is shown on five screens, which are positioned so you can’t watch them all at the same time. Three young women, too old to be children and too young to be adults, dressed in the swimsuits and playwear of a bright, bold summer, present a series of tableaux: innocence flirts with adventure, beauty conceals the inevitability of loss, life is poised on the edge of wonder and also disappointment.

We stare at the women, and they stare back at us. The subject is the male gaze, and everyone — artist, models, viewers — is complicit in it.

Through an interpreter, Metro spoke with Shanghai-based Fudong when he visited in late September.

I’d like to start by asking how you describe your work.

I feel my work is very changeable. Sometimes, when I look at it again, I feel like I’m looking at somebody else’s work and there is quite a distance between me and my work.

The Coloured Sky: New Women II was commissioned in New Zealand and Australia, but is it made for a Chinese audience too?

I want to create really specific works out of my own heart. When I’m making my work, I don’t have much consideration for whether it is for local Chinese people or for people from the West.

Ah, the good artist works for himself. Do you turn down requests to do certain kinds of work?

I hold a realistic view about what I can do and cannot do. Normally I have lots of ideas, my imagination runs wild. But there are two main factors that stop me from carrying out those ideas. One is budget. The other is my skill, my technique.

You’re famous for creating work with urban themes, but most of the imagery in this show isn’t urban. It’s rural, and it’s mythical, too. Is this exhibition a good representation of your work?

I don’t literally represent an urban view. I sometimes use my work as a mirror. For example, with Yejiang/The Nightman Cometh, I’m using that as a mirror to reflect some of the urban life and the confusion in it.

It’s an allegory about modern life, with people who are very isolated.

That is partly what I want to represent. The loneliness. The coldness. It is a bit depressing, a bit melancholic, and that is the goal I wished to achieve.

We’re not seeing everything that was in Melbourne. We’re not seeing The Wild Dogs. What are we missing?

I do feel it’s a shame that The Wild Dogs is not being shown in Auckland. It comes down to the limitations of the space. It’s a really good work — six screens that represent my childhood, the scenery of my village. And I really wish the work could be here; however, it was not possible.

Animals are very important in your work. Why animals?

Animals in my films are symbolic. For example, the horse symbolises loyalty. The hawk symbolises spirituality, and even the snake symbolises the winding future, the future that is changeable, the future that is not straightforward.

However, I feel that everything in my work is quite important, including the landscape, the weather.

New Women II is voyeuristic. We stare at these women in their bathing suits and they stare right back at us. They challenge us. I assume that’s deliberate.

The innocence of the women is almost to me like a little girl opening up a book and taking out a collection of candy wrappers, then holding those candy wrappers out towards the sun, and the sunlight goes through the candy wrappers, making different colours. That’s the kind of purity and innocence I’m pursuing.

There is also the example of a spinning top. It has different coloured stripes on it, but when you spin it, it becomes white. So it’s the difference between expectation, which is the really colourful, a really dreamy world, and reality, which is when the little girl grows up and everything blends together. I want to challenge the notion of which one is reality and which one is a dream. Which one does the audience want to believe?

And that’s why they stare at us while we stare at them?

It is almost like they are looking in a mirror. Their understanding regarding the desire, the temptation, all that kind of stuff, is really represented in what they see as they look in that “mirror”.

Which is us. Desire and temptation wrapped in images that are innocent: it’s very powerful and very unnerving.

This reflects the perceivable change from a young girl to a woman.

Does it also relate to the animals? They’re full of potential energy. They’re still but they might run. The women are like that, too. They have an animal quality, not in the sense of beasts, but in the sense that something might happen that changes everything.

I think the animals almost form the breath of my work.

The breath?

The breath, yes. That is correct.

I wanted to ask also about what is not drawn. The sense of yiu bai, that what’s important in the work is not just what we see but what is left to the imagination.

There are certain things I want my audience to see. But more importantly, I want them to be the second director, and to come up with their own understanding and narratives.

Is there such a thing as contemporary Chinese art? Or is that too broad a topic?

Like in other countries, contemporary art in China is really prosperous. I was born in the 70s; my thought, my style, might be different from the artists born in the 80s or even in the 90s. The young generation is getting really international because they have more access to the internet.

Are you saying you feel old?

I do feel that I’m old, but that doesn’t stop me from studying, from learning. I think by “old”, it’s more like ideology. There are lots of new gadgets in everyday life, so you need to continually update yourself.

Where do you place yourself in contemporary Chinese art?

I do not bear a lot of responsibility in terms of contemporary Chinese art. It is like a garden, and I am just one tree in this garden. And I am just doing my work with integrity.

Are you tempted to live in the West? If you take someone like Ai Weiwei, he lived in New York and clearly it informed his art. Do you feel tempted to do that?

I would say I prefer to travel as a tourist, but so far I haven’t decided if I want to live in any Western countries. One of the main obstacles for me is the language barrier.

What is the hardest thing for you to do as an artist?

The thing that makes me most uncomfortable is the distance between what I want to achieve and what I can achieve. Whether it’s because of the budget or something else.

The creative gap?

The creative gap, that is correct.

The gap between what you see in your mind’s eye and what you end up doing?

Yes. My way is to not try to completely achieve it, but to get as close as possible to the goal.

Is there something you haven’t done yet that you really want to do in your art?

I want to do feature-length movies. I want to do them on an annual basis and I can even do them until I am 60 years old. I say this jokingly. I have a plan for a library of movies.

Why stop at 60?

In fact, I want to go for 22 movies. I don’t know the specific reason, but in Chinese, I think 22 sounds really good. It is a perfect number for me.

Yang Fudong: Filmscapes. Auckland Art Gallery, to January 25. aucklandartgallery.com