Jun 8, 2018 Art

In March — owing to one man’s baroque levels of tenacity — an exhibition featuring 12 works alleged to be by the late great New Zealand modernist artist Frances Hodgkins opened on Waiheke Island. Some prefer it hadn’t.

“She was also one of the women artists who, by their example of single-minded dedication to career, challenged the category ‘lady artist’ with all its connotations of curtailed achievement.

“In August 1940, she wrote to her brother: ‘My aspect of the family talent, or curse? has taken the form of a deep intellectual experience, a force which has given me no rest or peace but infinite joy & sometimes even rapture’.”

Andy Boston was in high spirits himself back in 2015, when a package arrived at his Waiheke Island hilltop home from England, from an eBay trader called Elaine Nisbet. Boston and his partner, Melissa Honiss, had paid Nisbet a few hundred dollars each for 12 works, six of which were signed “Frances Hodgkins”. The consignment contained four drawings; three watercolours; two oils; and three textile designs. “We were like little kids,” says Boston, who filmed the occasion. “It was like bloody Christmas. It was such an honour to be unwrapping something that no one had seen for a long time — even if they’d ended up not being hers.”

Andy Boston was in high spirits himself back in 2015, when a package arrived at his Waiheke Island hilltop home from England, from an eBay trader called Elaine Nisbet. Boston and his partner, Melissa Honiss, had paid Nisbet a few hundred dollars each for 12 works, six of which were signed “Frances Hodgkins”. The consignment contained four drawings; three watercolours; two oils; and three textile designs. “We were like little kids,” says Boston, who filmed the occasion. “It was like bloody Christmas. It was such an honour to be unwrapping something that no one had seen for a long time — even if they’d ended up not being hers.”

Boston is a sometime event manager and caterer. In 2000, drawing on his experience as a then single father, he wrote a book provisionally entitled “Mr Boston’s Guide for Home Duties”— a 21st-century Mrs Beeton’s for men. It wasn’t picked up by a publisher: “They weren’t ready for it,” he says. Boston is also an inveterate collector and trader, who has come a long way since his days as a child philatelist, recently listing a painting attributed to the 19th-century artist Charles Blomfield on Trade Me, with a reserve of $45,000. “I’m a bit of a social anthropologist,” says Boston. “I have spent the last 15 years bringing New Zealand antiques, collectables and art back.”

Repatriations don’t always go smoothly. In the case of Boston’s alleged Frances Hodgkins, provenance is murky. Boston reports that Nisbet (who didn’t respond to Metro inquiries) had bought them at an antiques fair in Lincolnshire, from a dealer who had come across them as part of a job lot in an estate clearance in Dorset, where Hodgkins died in a psychiatric hospital in 1947.

Nisbet had wandered into unfamiliar territory: she deals predominantly in “things like fox hunts”, says Boston. Nevertheless, “she recognised the name, got excited, and bought without asking further questions — obviously not wanting to alert him to the potential”, Boston adds.

The wily Nisbet then took to Google, and landed on the website of Parnell-based art dealers and auctioneers International Art Centre, perhaps clicking on the centre’s auction tab, which documents recent Hodgkins activity: in 2015, her oil on canvas Monastery Steps had fetched $320,000; in 2014, her water colour Mediterranean Courtyard $15,000. Nisbet emailed images of her Lincolnshire find to the centre; a reply came back along the lines of “no cigar” — at which point Nisbet retreated to eBay, and hooked Boston.

“I didn’t know a huge amount about Frances Hodgkins, other than, to be quite honest, through collecting stamps,” Boston says, referring to the 1973 New Zealand Post Office issue featuring four Hodgkins paintings. Undeterred, Boston “had a look at the signatures, did some comparisons… and I thought, ‘Well, these are actually worth a look because they’re not pieces that are obvious forgeries, they’re not pieces that somebody has done because it looks like a Frances Hodgkins artwork and they want to pass it off as such’.”

On the other hand, Boston has put some points on the board and had a relatively good run in the media far and wide, which has rendered the circumstances surrounding the discovery of the alleged Hodgkins a deal more colourful, if not significant. The Dorset Echo interviewed Boston over the phone and headlined its story, “Bunch of tatty old papers’ found in Weymouth house clearance uncovered as rare works of a famous New Zealand artist”, reporting Boston was part of a Hodgkins curatorial project. (The journalist “misconstrued” that last bit, Boston tells Metro.) The New Zealand Herald interviewed Boston and headlined its story, “Rare cache of paintings by famous NZ painter Frances Hodgkins surface in English attic”, reporting that “Frances’ thumb” was all over one of the works. The Otago Daily Times, however, tacked differently with its story “Art authenticity questioned”, detailing a skirmish at the Otago Art Society (more later).

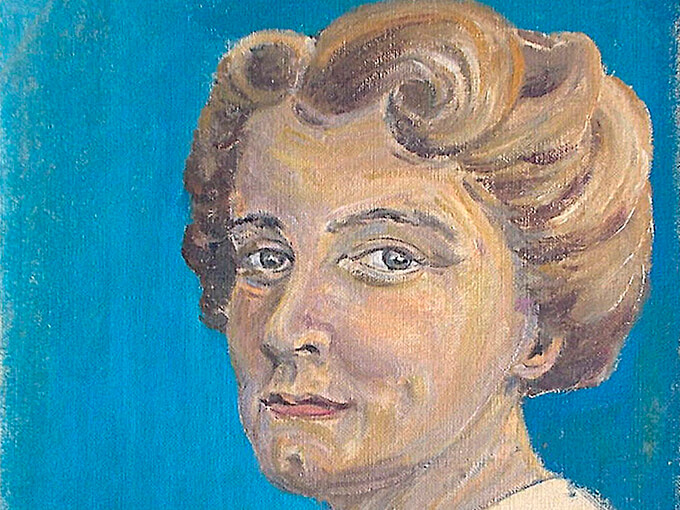

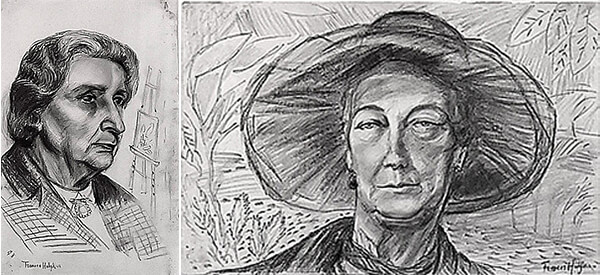

Boston contends that Hodgkins made the 12 works in the 1930s and 1940s. She did not intend them for “public consumption”, he says, the subjects being too personal. Three of the drawings are self-portraits — one of herself as a 12-year-old (figure 01), Boston says. They are unusual because Hodgkins was not known for her conventional self-portraits — unusual but not inexplicable, says Boston, because Hodgkins changed styles frequently. He maintains that among his collection are likenesses of Hodgkins’ friends Dorothy Selby and Cedric Morris and her father, William Mathew Hodgkins, himself an amateur landscape painter of some note. Boston admits his collection is not representative of the artist at her best. “But why are they not [Frances Hodgkins]? You can’t just tell me it’s because she never did anything that bad. Because she did do stuff that bad. She destroyed a lot of stuff herself. She was unable to hold her pencil sometimes because of her arthritis. She had her manias,” says Boston, who has read Linda Gill’s landmark, door-stopping 1993 collection Letters of Frances Hodgkins twice. “Frances says in her letters how she hates how her critics and dealers ask her to stop experimenting… sorry, she was continually evolving, continually changing,” Boston says, pointing energetically to the works propped up around his living room. “And these were not things that were made to go on a bloody… hang on an exhibition rail and be sold.”

And yet. Boston has sought the imprimatur of the International Art Centre and other auctioneers, dealers, and public institutions: Dunbar Sloane; Jonathan Grant Gallery; and Gow Langsford Gallery; the Auckland Art Gallery, and Auckland University, among others. He has also offered an exhibition of the works to the Waiheke Community Art Gallery, the Mahara Gallery in Waikanae and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

Boston’s knock-backs — via email at least — have for the most part been diplomatic, as have his responses. When a former director of a public gallery advised caution in attributing the textile designs to Hodgkins — sure, they were consistent with her modernist aesthetic, but were more roughly painted than designs held in Te Papa’s collection — Boston replied: “All I want to do is prove their authenticity. I believe they are real and feel an injustice on Hodgkins’ part that they are being doubted. I have become one of her biggest fans, not just on an artistic level but as a human being who remained true to her calling despite massive hardships. I look forward to continuing this challenge and once again thank you for your response. Kindest regards, Andy.”

To a professor of art history, who after seeing the works in person expressed incredulity to Boston and wished him well in his art career, he replied: “Wow! I would really like to know why you think it is a joke and what potential explanation you have for the works’ existence. These items were found in a house clearance in Weymouth. That is the fact. As for my ‘art career’ we have a collection of New Zealand works that we have purchased over some time. This is not a ‘have’ … Kind regards.” And to an art dealer who pointed out that Boston had misspelt Hodgkins’ name in exhibition material, he replied: “You truly are a pompous individual. Go well.”

One of Boston’s first approaches was to Mary Kisler, a curator at the Auckland Art Gallery who for the past three years has been researching Hodgkins as part of a gallery project which will culminate in the launch of a Hodgkins show in April 2019, along with an online catalogue raisonné (a list of all an artist’s known works, with accompanying comment). Boston offered to make the trip over from Waiheke with his haul: “I smile as I write this, partly because I have been grinning from ear to ear for a number of weeks now and also because I know you are about to have a moment you will never forget.” Kisler asked if Boston intended to sell any of the works. “I am undecided as to what I will do but my initial thoughts are to sell some and retain others, but regardless, they need authentication, and more importantly for your database, documentation,” he replied.

The meeting never took place — Kisler was in Europe scouting for Hodgkins to include in the catalogue raisonné. “You don’t arrive at decisions lightly,” she tells Metro. “You look and you look and you look, and you think, and you compare and you wait and you come back because sometimes you see something in another work that is linked. It has to fit.” Kisler has scrutinised 1500 Hodgkins to date; the gallery holds 92 of those in its collection.

On the specific issue of Boston’s three self-portraits, Kisler has this to say: Hodgkins didn’t like being photographed, maybe because she was an older woman competing in a young modernist market. She also never painted a traditional self-portrait, but instead created semi-abstracted groups of her favourite objects — a pink shoe, scarves, belts, jewellery, flowers — like a post-modern metaphor for the self. On the other issue of the six signatures, in which Boston places great store: means nothing, Kisler says. A friend and student of Hodgkins, Hannah Ritchie, once cut Hodgkins’ signature from one of her paintings in order to practise it, so she could collect a money order for the artist. In one letter, Hodgkins writes that she is unsure whether she or Ritchie had signed a work.

Across the road from the Auckland Art Gallery, at the private art dealers Gow Langsford Gallery, director John Gow recalls a phone encounter with Boston, tangentially related to Boston’s The Hidden Portfolio. Last year, Gow — a member of the committee that verifies works to be included in the Auckland Art Gallery’s online Hodgkins catalogue raisonné — saw a watercolour on Trade Me, purportedly by Hodgkins. It was a bad Victorian watercolour of a subject and style that bore no relationship to Hodgkins, he says. Boston was the vendor. As Gow was weighing his options, Boston rang, and things took a turn to the surreal.

“I said, ‘Andy, I’m giving you a heads-up. You either take it down or I’m going to write something on your site which is really going to affect your ability to trade on Trade Me.’ ‘Is that a threat?’ I said, ‘No. I won’t have someone buying a Hodgkins when it’s not.’ ‘You don’t know it’s not.’ I said, ‘I do.’ ‘Well, how do you know?’ ‘That’s a very difficult question to answer,’ I said, ‘Because I’ve been dealing with her work for 35 years. I know a Frances Hodgkins when I see one and that is not one.’ He said, ‘Well, that doesn’t mean anything.’ And then he got quite aggressive and I said, ‘I’m not really interested in taking this conversation any further, but there is no expert in the country who will authenticate that work.’ ‘Yeah, well, you all stick together, don’t you?’” Gow to Metro: “You bang your head with these people and they won’t believe you because, what do you know?”

On Boston’s part, he recalls Gow telling him the watercolour wasn’t authentic because Hodgkins never applied paint that way. Gow “told me to bring it to him and said the Hodgkins committee would decide whether it was authentic or not”. It was an instruction that Boston ignored: “I chose to remove it from Trade Me and authenticate it via other means. It is signed and dated 1914 and comes from a short period of time that Hodgkins was teaching students in a small coastal village in France. I am confident it is authentic and will wait till after The Hidden Portfolio debate has run its course before bringing it back to the light of day.” When pressed about authentification, Boston told Metro that “as of yet I have shown it to no ‘expert’, including handwriting analyst, in the flesh”.

In order to sidestep the opprobrium of the art world, Boston has turned elsewhere — to the world of forward slants and radial loops. Regrets — over in Pt Chevalier Mike Maran has a few. Boston engaged Maran, a recently qualified member of the Scientific Association of Forensic Examiners, to scrutinise those six signatures. Maran used as his point of comparison Hodgkins’ signatures in books. “Looking back on it, I’d really need to authenticate them against her original paintings,” he says. “If he [Boston] would have said to me, ‘There’s an original painting at the art gallery in so and so city, go to that and compare apples with apples’, then it would have been a bit more… ”

Maran’s report “Re Authentication of Francis Hodgkin’s Signature on original paintings” was displayed at both Studio One Toi Tu and the Otago Art Society. It makes for a brow-furrowing read. In among the technical lingo — the slant of the downstroke of the H is similar at 70-degrees reclined, lower zone ‘g’ pulls to the left; pen lifts between the “n” and “c” — is Maran’s conclusion: “I can state with scientific certainty that it is highly probable that the signatures attributed to Francis Hodgkins … are authentic.” However, Maran also says: “[In] Three of the paintings the images were satisfactory and another 2 were below average for analysis purposes.” Also: “When signing the painting the artists [sic] arms may not have been supported on a stable surface.” And, “I am informed that Francis Hodgkin’s had many emotional or personal influences throughout her life and this was reflected in her changing signature style. Known as natural variation.” And then: “Except where the images were faded, all the letters within the signatures are legible.”

“I’ve upped my game a bit since then,” Maran tells Metro in a conversation in January, which went like this. Metro: Do you realise you misspelt Hodgkins’ name? Maran: “No. I wonder why he [Boston] never picked it up. But when I was authenticating the paintings, I wasn’t going on the spelling; it was more the handwriting traits.” Metro: Were you aware that Hodgkins sometimes had other people sign her work? Maran: “Those other people have probably practised the signature to such an extent that it does look authentic.” Metro: From your report it sounds like only four of the six signatures were fit for analysis? Maran: “Yeah, that’s right. If you want to phrase it another way, [with] the other two that were below average we would probably say that they are probably probable… Yes, probably I should have rephrased it in some ways. I’ve actually now got to adhere to a code of ethics … I may say that the resolution is so faded I can’t make head nor tail out of it. I would just have to put ‘inconclusive’. But back then I was a bit… green. Now I’m a bit more mature and cautious.” Maran segues: “The story behind it is a bit far-fetched. They were found in his [Boston’s] mother’s flat in London or something. Is that correct? In his deceased mother’s flat?” Metro: Um. Maran: “Don’t take my word 100 per cent. I’m just going on memory of a conversation when he first came here.”

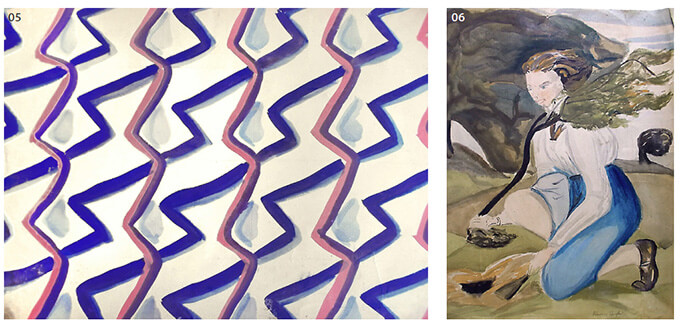

Boston also used the services of former policeman Peter Burridge, now of Fingerprint & Forensic Services in Takapuna, distilling the findings for The Hidden Portfolio exhibitions in Auckland and Dunedin like so: “A number of partial fingerprints were found under ultra-violet light; however, none were of a quality to allow a comparison with other fingerprints of Hodgkins.” And, “An interesting discovery from this exercise showed that the blue shape repeated in the Zig Zag textile [design, figure 05] was in fact made with a downward sweeping motion of a thumb.”

When Metro first contacted Burridge, he agreed to talk about his findings on the proviso that Boston give him written authority to do so. When Boston obliged, Burridge reneged. “It’s a bit of a palaver!” Boston emails. “Peter’s findings were all related to me verbally at the time, but for some reason he doesn’t appear to want to either confirm or deny anything now… From my point of view this only hardens my resolve to have the truth come out,” Boston continues, before attempting to compensate for Burridge’s silence and answer questions, such as: Where are those other fingerprints of Hodgkins held? In what circumstance would Hodgkins have been fingerprinted? How could the New Zealand Herald journalist Kurt Bayer have been under the impression in a caption accompanying his 2017 story “Rare cache of paintings by famous NZ painter Frances Hodgkins surface in English attic” that one zig-zag textile design features Hodgkins’ thumb as a recurring motif?

“I do not know of any Hodgkins fingerprints on record,” Boston replies, “but as she was a prolific letter writer, one could assume that amongst the 1000’s of letters held at the [Alexander] Turnbull [Library] there would potentially be fingerprints that could be lifted. Obviously the costs and expertise involved in going down that path would be prohibitive. Peter came up with the summation that a thumb was used by the artist in the zig-zag design although this has not been identified as being specifically Hodgkins thumb and is a downwards smear rather than distinct print.” Notes Boston: “I would happily sign an affidavit that all information in the written blurb pertaining to the blue light examination is 100 per cent accurate if that was what was required.”

Boston’s information, relying as it did on both Mike Maran and perhaps Burridge’s findings, was enough to persuade Nic Dempster, president of the Otago Art Society (OAS), that he had done the right thing in hiring out space to Boston to exhibit The Hidden Portfolio in Dunedin in March last year. “Andy was very up front with all his reasoning… and he put all of his investigative theories on his display with the work, so we thought at the very least it was creating a dialogue with people and creating interest in the artist.” After all, says Dempster, “it was just a private hire. People can hang whatever they like in there, we don’t have any say. I’m not comfortable with us stepping into that role of censor.”

It was a position some felt was supine, and for which he coped flak from “these outside people from Auckland” that left him feeling not a little intimidated. Mary Kisler, Linda Gill (another member of the catalogue raisonné committee) and Liz Eastmond (retired art historian and co-author of Frances Hodgkins: Paintings and Drawings) asked Dempster — politely and vehemently — to put up a warning notifying visitors that authorship of Boston’s works was contested, noting that the OAS had been important in Hodgkins’ life — she had exhibited there as a professional artist in 1890, and her father founded the OAS in 1875. The “nastiest” email, says Dempster, came from a man whose name he can’t recall. The entreaties came to no avail, although Dempster did allow Eastmond to write a piece for the OAS newsletter. “I don’t think we’re so fussy down here,” says Dempster. “I think we’re more down to earth. We take people at their word. I think there’s a lot of infighting in Auckland.”

Coverage of the affair in the Otago Daily Times (“Art authenticity questioned”) has left Boston smarting. Kisler was among those interviewed for the story. The gloves came off. “She said Mr Boston did not know how to read what was by Hodgkins and what was not,” reported the ODT. “She was worried someone would be ‘hoodwinked’ and pay a large amount of money for one of the works thinking it was the real deal. People had ‘genuinely tried to point out to’ Mr Boston the works were not by Hodgkins and had not treated him unfairly. ‘I feel sorry for him on one level, but at the same time I think it’s disrespectful to a major artist.’”

“Bloody patronising,” says Boston. One of the things that irks him is that Hodgkins experts and scholars have given no credence to the scientific evidence he has amassed. “Where’s the balance? I’m a Libran. Where’s the balance? Is all of the scientific evidence equal to the opinion? Or does the opinion still outweigh the sum of the scientific stuff? Or what? Because I’m sure experts were consulted when they bought that Lindauer,” Boston says, referring to the Alexander Turnbull Library’s 2013 purchase of a Lindauer at auction for $75,000. Two years later, the institution was red-faced when Auckland Art Gallery conservator Sarah Hillary proved it was a fake, having found a pigment that was not available in Lindauer’s day.

One expert, however, had called it. Before the Turnbull bought the Lindauer, it sought the advice of colonial art expert Roger Blackley of Victoria University, a former Auckland Art Gallery curator, who advised against the purchase.

Blackley runs his eye over Boston’s 12 images. “The thing about authentication is that it’s not the province of any single apostolic announcement. It’s consensus. So, for these to be accepted as works by Hodgkins, everyone, or at least most experts, would have to agree. Put succinctly, what Boston wants is to realise a profit, and for that to happen, experts would have to agree that they are by Hodgkins. None of them will, so therefore they are worthless.”