May 13, 2019 Books

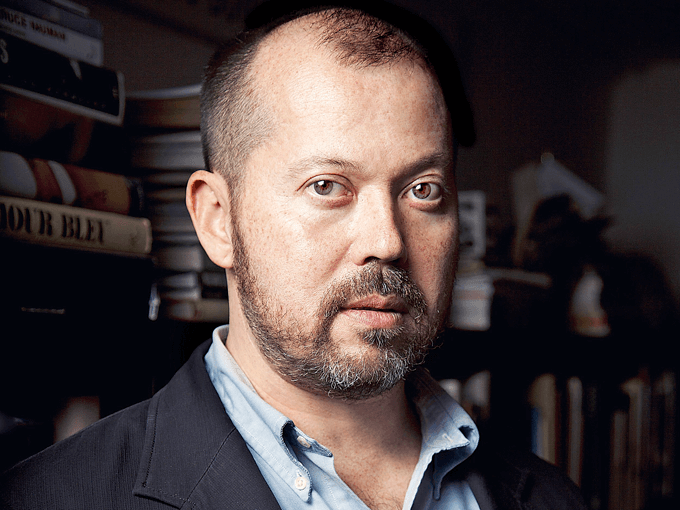

For Korean-American novelist Alexander Chee, writing non-fiction is a high-wire act, but not one performed for entertainment.

“I have an endless fascination about my ability to see myself. I feel like I try really hard to catch myself at that… I suppose I’ve come to regard myself with a kind of affectionate suspicion.”

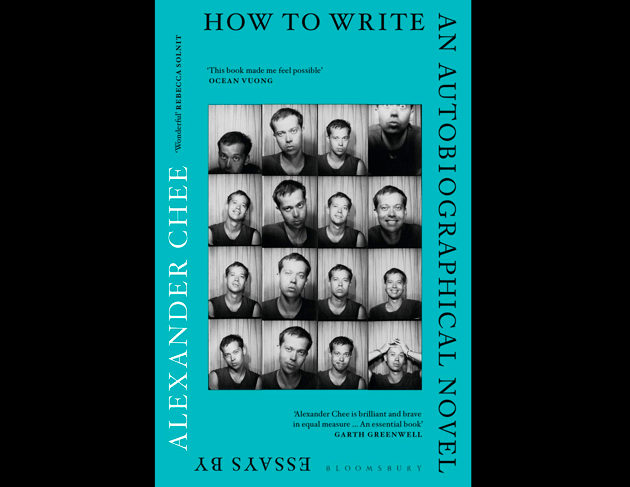

In a telephone call on vacation in Idaho Springs, Colorado, Alexander Chee inadvertently sums up the reason behind the emphatic success of his first collection of interconnected essays, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. This affectionate suspicion is seen so clearly in the impressive breadth of topics he covers, from tarot card reading — which he once did professionally — to the cultivation of a garden, a teenage summer trip to Mexico, the Aids crisis, and, of course, writing.

Chee’s debut novel, Edinburgh, about a 12-year-old Korean-American boy, Fee, who is sexually abused, and the trauma that comes after, was awarded the Asian-American Writers Workshop Literary Prize and the Lambda Editor’s Choice Prize; his second novel, The Queen of the Night, is a sprawling historical fiction set in the Paris Opera.

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel is Chee’s first non-fiction book, which he says stemmed from being invited to speak at Columbia University’s Non-fiction Writing Programme and realising he was the only person in the reading series who didn’t have a book of non-fiction. “I was a little embarrassed, you know, like, who do I think I am?” He already has two other non-fiction books in the works, a second collection of essays, and a book of writing instructions, in Chee’s head jokingly titled Really How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

For Chee, essay writing is a moral and ethical high-wire act, and not to be taken lightly. “It’s not done for entertainment — or at least, I’m not doing it for entertainment. I’m trying to convey what I’ve learnt at a great cost in this life.” There’s an example of this in the essay “After Peter”, about an artist Chee knew briefly (“I am a minor character in Peter’s story”) who died of Aids in the 90s. “When I thought about the real cultural costs of the epidemic, it seemed to me that it was the artist who would never produce the major work of their lives. So to try to write about that is… You’re writing into something which doesn’t exist, that was obliterated by death, and illness in this case. And so the way in is not obvious at all. I wanted to make him exactly as important as he was, if you understand me. I didn’t want to make bold claims, and neither did I want to underplay what I thought was his real potential. So that involved a reported essay — doing interviews with his families, his friends, his ex-lover. It was intense.”

The essays so intimately explore the various identities which Chee embodies — gay, Korean-American, artist, writer, activist and son, among others — approaching past events with an empathetic self-investigation that feels daring, yet recognisable. So is it inherently more vulnerable than fiction? “I remember people used to ask me, ‘Does it make you feel vulnerable to write about yourself so personally?’ And I’d always think, ‘What do you mean? I’m writing about old pain — how could that make me feel vulnerable?’ But then once these essays were all together in a book, as it were, that suddenly made me feel definitely vulnerable in a way that felt new.”

As he is also a teacher who has taught fiction writing at Columbia University, the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Wesleyan University and is currently an associate professor at Dartmouth College, it feels unwise not to ask for a little advice. I ask about when writers get stuck, and he talks about the common fear of other people’s reactions. “There’s this mistaken idea that your silence will be the thing that protects you. Instead of using these concerns as a guide to how you construct the piece, you stopped. What you have to do is figure out — like, be really honest with yourself — is that person you’re afraid of more important than you? And what exactly do you fear, and can you name it? Usually people don’t even go as far as acknowledging that. They just freeze. It’s a completely irrational thing to do to not be a writer because you imagine one reaction a person might have to the thing you write. And so often the situation I find myself in as a teacher is listening to someone patiently explain to me, of course they could never finish this, because of this one person who might possibly be mad at them about it.”

Chee is the first openly gay Korean- American novelist. In “The Autobiography of My Novel”, he writes, “I was forever finding even the tiniest way to identify with someone to escape how empty the world seemed to be of what I was.”

Do you now, I ask, see your writing as a political act? “I do, quite frankly. Someone was asking, ‘Was I comfortable with my niche, of always being in a niche?’ I said, I fought hard for that niche. I sacrificed a great deal for it, and now other writers are joining me there, and I love that. What was so moving to me about touring with this book is meeting so many young Asian-American, old Asian-American and queer Asian-American writers who felt a connection to the book, and through that getting a glimpse of what’s possibly going to be appearing next in this world. It is political now, has been political since the beginning, and I imagine it always will be.”

As part of the Auckland Writers Festival, Chee is taking part in The Good Immigrant panel with a fellow contributor to the essay collection The Good Immigrant USA, Porochista Khakpour, and New Zealand author Rosabel Tan. “The word ‘immigrant’ has become such a politically charged word thanks to the weirdly identical efforts of both the US and UK to really attack not just immigration but also naturalised citizenship. So this is just what has to be done. But it’s not speaking to an imagined sense of who those people are who might reject that; it’s also about making these subtle and as yet illegible spaces inside us legible to each other, to talk to each other.”

And on the writers festival in general, Chee says, “The writers’ celebration is the readers’ celebration, too. There really is something different about seeing a writer in person and connecting to them in that way, to hear them think out loud in relation to the questions, or to just have their voice in your head when you go back to their work. There’s also a community conversation. The festivals invite these writers in because they believe they will connect to the community; there’s a way that the community gets to think about itself that it might not otherwise, and writers play a role in that. And I take that role very seriously.”

Alexander Chee appears at the Auckland Writers Festival, 17, 18 & 19 May 2019.

This piece originally appeared in the May-June 2019 issue of Metro magazine.