Aug 18, 2025 Art

At the apex of Mumbai’s cultural calendar is Gallery Weekend, a prestigious occasion when the city’s art scene bursts into a heightened state of liveliness. For the 11th edition, in 2024, TARQ, a contemporary gallery in the city’s Fort district, presented As this chin melts on your knee — an assortment of works on paper, sculptures, embroidered textile panels and painted studies inspired by Tablet IV of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an ancient Mesopotamian odyssey.

Many of the works are populated by small stick-figure-like forms, some winged, in a frenzy of action as if on the verge of escaping from their pictorial confines. In one scene, a watercolour diptych belonging to a series of nine, Persepolis’s friezes are reworked to depict a woman leading a trio of men. Another scene from the same work shows vessels and vegetation from nearly obliterated Persepolitan artefacts — a flattened amphora and a gilded bowl — reclaimed through acts of conjuring, or, to use the gallery material’s words, “queer acts of fabulation”.

Other rooms housed an assortment of bricks and ceramics in muted, earthy tones, sober in contrast to the jewel-box polychromy of the watercolours and the multicoloured embroideries. Some ceramics were etched, somewhere between text and image, using the artist’s nail, a needle or a stick. Kaolinite clay, raku and Caspian Sea sand were listed as mediums. If their material vocabulary spoke of a grounded earthiness, the suspended ceramic trinkets in the work Loom (2023) were more gravity-defying, hanging from cotton thread and casting geometric shadows. An adjacent collection of eight glossy, irregularly shaped bowl-like forms echoed several other curves throughout the show: horseshoes, spikes, spirals, embroidered concave patterns and a coiling serpentine form.

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Install. TARQ Mumbai, 2024

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Install. TARQ Mumbai, 2024

For the exhibiting artist, Areez Katki, it was no small gesture of confidence to be offered such a prime spot during this notable event for an international audience. As Katki told me one afternoon over a video call: “It didn’t feel the same as exhibiting back home in Aotearoa, it felt global — more connected to multi-directional solidarities in the Global South.”

But where exactly does a Mumbai-born, Oman-, Emirates- and Aotearoa-raised artist of Parsi ancestry call home? It’s a knotty question, probing into inherited affinities and those the artist has chosen to cultivate for himself. The discussion of diaspora often lapses into cliché: the lost home, the sense of being neither fully here nor there. Diasporic art, too, can become stuck in a self-indulgent loop. Yet beneath the surface of hackneyed expressions, some questions beg to be answered: when does an emissary become a native informant? How, if at all, is a line drawn between research and extraction? Before I could even ask, Katki suggested with preemptive self-awareness that “the whole nature of return has this narrative of wayfinding and sometimes, it can feel a little too close to that white saviour kind of thing”.

Katki lives and works in an art deco apartment complex that forms part of Sir Ratan Tata Parsi Colony in the Tardeo region of Mumbai. Once home to four generations of his family, the location holds the weight of memory and now a new sense of duty: Katki took on a role as its custodian in 2017, living and working there after his grandmother had vacated the home and relocated to Aotearoa the year before.

Areez Katki, Intermezzo. As this chin melts on your knee. Install. TARQ Mumbai, 2024

Areez Katki, Intermezzo. As this chin melts on your knee. Install. TARQ Mumbai, 2024

When we spoke over video in August last year, Katki told me of his ongoing efforts to funnel his possessions from Aotearoa to Mumbai — a return of sorts to the place of his birth. A significant part of his book collection is now in Mumbai, part of which formed a neat stack of spines behind him on my screen. It was a fitting backdrop for such a research-oriented artist, whose source material ranges from ancient epic poetry to contemporary autotheory. I noticed one title placed cover-forward: a catalogue for There Is No Other Home But This, a two-person show of work by Katki and Khadim Ali at Ngāmotu New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in 2022.

Ceaseless itinerancy is a hazard of the job for the practising contemporary artist, and the residency its primary form. By the time of our call, Katki had been in Mumbai for nine months, but his thoughts were turning towards Aotearoa, this time to arrange a visa to enter Germany for the CNZ Berlin Visual Arts Residency he was about to take up. As the 2024/2025 resident, Katki receives the use of an apartment in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, a stipend of $40,000, a place in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien studio programme and support for a solo exhibition in the middle of the year.

In his travels, Katki is always learning and observing, absorbing and metabolising the world around him. When we first met at the University of Auckland, both of us undergraduate art history students, he already exuded a worldliness beyond his young age and the provincialism of Euro-American art histories that abounded in our syllabi. Katki sharpened his literary and art historical know-how while pursuing a double major in art history and English, and still effortlessly draws upon this intellectual training, both in his work and in everyday conversation. “There’s that part of my brain that still works,” he says.

For the Berlin residency, Katki proposes to look back at his 2019 exhibition Bildungsroman at Malcolm Smith Gallery in Howick, Auckland (reprised two years later as Bildungsroman & Other Stories at TARQ). Named after a genre of coming-of-age novels, the exhibition used craft to trace the roots of Zoroastrianism, the religion into which Katki was born, while also critiquing its patriarchal structures and examining the complicated relationship that he as a queer person had to his faith.

Working against this patriarchal background, Katki constructed a pantheon of female divinities and other influential figures, which includes his now-late grandmother, Thrity, from whom he learnt many of the techniques used in his practice. Thrity looms large in Katki’s life as someone who shaped him both personally and artistically, later becoming a collaborator on some of his pieces. The phrase “The Temple of Women”, sewn in shorthand atop a pediment in Temple of Anāhitā from his Agiary Series (2018), signals this mission and points to Katki’s north star. In numerous ways, the work in Bildungsroman was an ode to the domestic sphere from which Katki derived so much of his intellectual and artistic development. The artist also made explicit nods in the exhibition to his queerness: “GOD BLESS OUR HOMO” on a beaded toran and a mass of small phalluses on Hoshang Merchant Takes his Vitamin D (2018). The original Bildungsroman emerged from a nine-month trip to sites from Katki’s childhood in India and places of significance to the Zoroastrian faith. It was, as the title declared, a significant moment in the artist’s formation.

Strategies of autofiction are central to Katki’s reappraisal of Bildungsroman and its themes. Autofiction, a much-contested subgenre, has fielded charges of being no more than an exercise in white, middle-class navel-gazing, with some critics denying altogether its utility as a literary category. How, then, does an artist like Katki, who seems so invested in a full-throated critique of Western, anglophone imperialism, find himself roaming its pastures? Is there some kind of conflict here, some abdication of his aesthetic and political commitments? Katki was able to study the problems of autofiction in 2020 as he worked, not without reservations, towards a master’s degree in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington. While he admits he has occasional unease in navigating these texts, he has found ways to mine the body of fictionalised autobiography for what he requires. A chapter in Jacqueline Rose’s Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty that focuses on Elena Ferrante particularly stood out to Katki. It highlighted Ferrante’s sharp insights into the complexities of motherhood, a topic Katki has long been deeply interested in — from mythical dimensions to everyday realities.

Areez Katki, Installation view, There Is No Other Home But This. Govett-Brewster, 2022. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

Areez Katki, Installation view, There Is No Other Home But This. Govett-Brewster, 2022. Photography by Sam Hartnett.

In 1989, Katki’s own parents, who had been based in Muscat, Oman, returned to Mumbai (then Bombay) for his birth. Before long, however, they returned to Oman for work, leaving the infant Areez in the care of his maternal grandparents. “It’s funny,” he reflects, “I’ve been thinking about attachment theory a lot lately. The idea of care, especially from people who aren’t parental figures. I think a lot about that in relation to my grandmother and the bond I had with her.”

After 10 early months in Bombay with his grandparents, Katki moved to Muscat, where he lived for three years before relocating to Dubai with his family at age four. It was in Dubai that his left-handedness was forced into right-handedness through a training regime which included having his hand tied behind his back. This corporeal prescription echoed the other social mores and gendered codes enforced on him directly and otherwise, including at his “conservative English kindergarten”. Decades later — around the time of his exhibition Some ribs are always soft in 2023 at McLeavey Gallery in Wellington — Katki began an act of reclamation by way of using and retraining his left hand.

A turn-of-the-millennium uprooting and move to Aotearoa, at age 11, brought less disciplinarian rigour but presented its own challenges. “I think my sister and I were kind of resentful initially of the move,” he recalls of their transition from Dubai, the fledgling hyper-modern behemoth, to the sleepy suburbs of Howick in East Auckland. “There were, as well, the feelings of unease that came from being a brown kid who had little-to-no tools by which they could explain their identity.”

For Katki, who was born in India but is not Indian in a genealogical sense, raised in the United Arab Emirates but not Emirati, of Persian descent but not Iranian, the task of neatly, legibly self-defining can be complicated. Finding one’s place, or a language to create such a place, can feel like sliding down a wall of misrecognition, grasping for something solid to hold on to. This can lead to strange moments of concession. “When I would come across someone who understood even a little of where I was coming from, usually some erudite white guy who knew what Zoroastrians were, I’d think, ‘Oh my God, you’re amazing.’ But then I’d realise, wait, no, that shouldn’t be remarkable. That should be the baseline.”

Fortunately, Pakuranga College, which Katki attended, had a diverse cohort. “What’s funny is that I didn’t feel the full force of dislocation, of being a perpetual outsider, until after high school,” he tells me, savouring the irony. It was the spaces that came later, places like Elam School of Fine Arts, that threw him into sharper confrontation with difference. Though Katki didn’t himself study at Elam, he spent a great deal of time with art students, including at the Elam Fine Arts Library, which was shared with the department of art history. At the time, the University of Auckland presented an academic system that often seemed to exclude Katki. “The art world there didn’t really have anyone who looked like me.”

If New Zealand academic institutions sometimes failed to deliver for Katki on their promise of edification, the curator Natasha Ginwala, who grew up in Ahmedabad, India, is one figure who has been an alternative source of instruction and support. Katki tells me how he had long admired Ginwala’s practice from a distance — that is, until he wrote to her via email, initiating what would become a generative months-long conversation. Following their exchanges she invited him to exhibit in the 2022 edition of Sri Lanka’s annual Colomboscope festival, of which she is artistic director. Ginwala, who ranked 54th on ArtReview’s 2024 Power 100 list, also holds curatorial positions at Berlin’s Gropius Bau and the current iteration of the Sharjah Biennial.

Areez Katki, Personal Structures, 2024, Palazzo Mora. Photograph by Federico Vespignani

Areez Katki, Personal Structures, 2024, Palazzo Mora. Photograph by Federico Vespignani

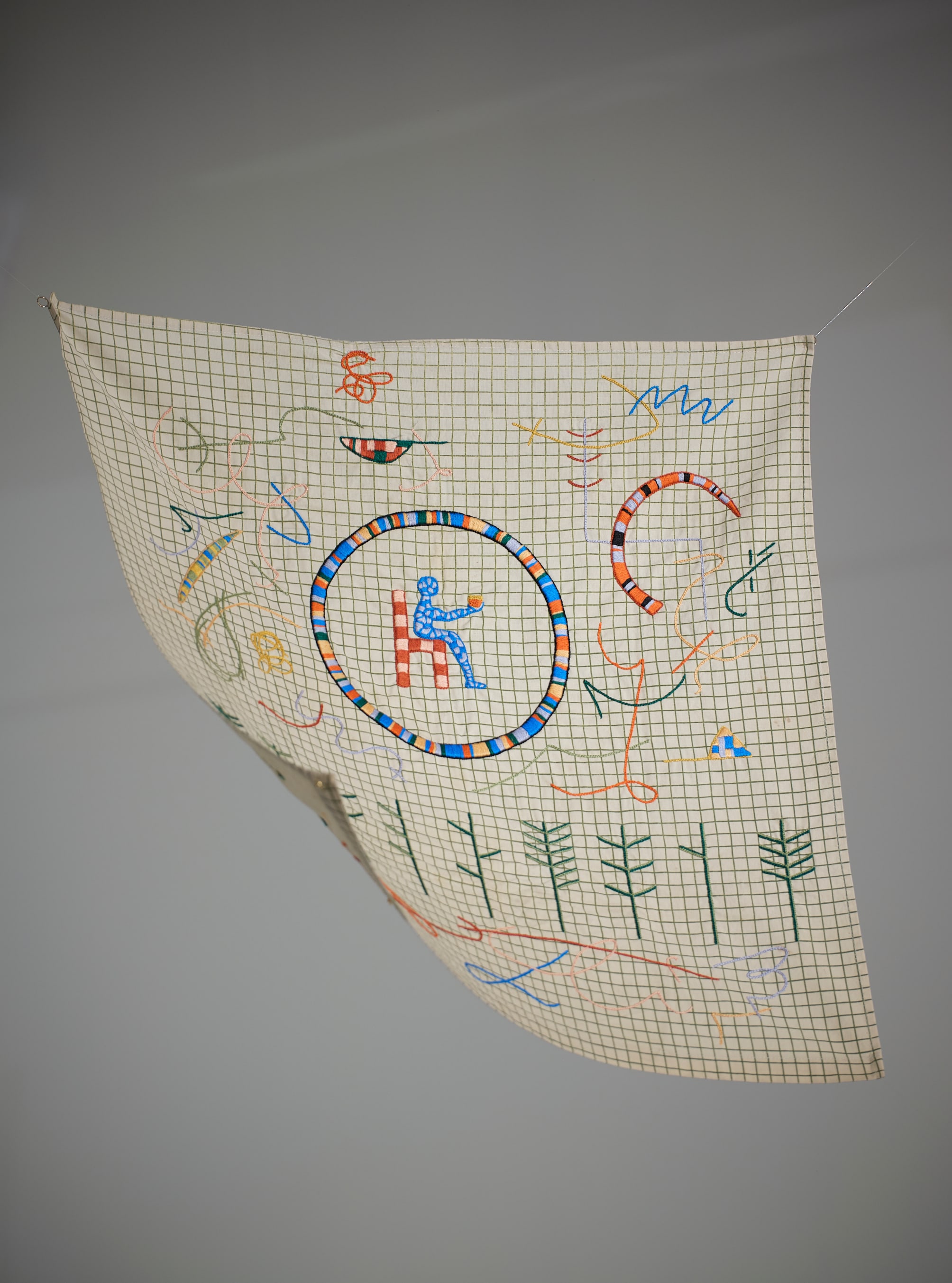

In early 2023, another illustrious opportunity came by way of an invitation to exhibit with Personal Structures, a presentation that takes place alongside the Venice Biennale. For the 2024 edition, Katki staged The Rhapsode’s Tools Will Build the Rhapsode’s House at Palazzo Mora. In his exhibition, 17 embroidered found-cloth fragments — a response to the 17 has of the prophet Zarathushtra’s Gathas, the foundational hymns of Zoroastrianism — were suspended at varying heights, accompanied by tiles of kaolinite clay sourced from the backyard of the artist’s family home in Aotearoa New Zealand. (That same clay was used for ceramics in As this chin melts into your knee.)

“I’d been to Venice before, as just a viewer,” Katki told me, “and I never really expected much from being an exhibitor, especially in one of the smaller collateral events.” Though many felt compelled to describe the 2024 Biennale in celebratory terms, Katki remains sceptical in his appraisal. For some, Pedrosa’s edition was an unalloyed victory for the Global South: the first presented by a Latin American curator and including a preponderance of so-called ‘global majority’ artists, queer artists and women compared to preceding editions. But in Katki’s words, “Venice is a machine, a spectacle.” What stood out to him, despite claims to the contrary, was its risk-averseness and lack of purchase on the most pressing political concerns of our times.

What Katki had hoped for at Venice, more than broad-brush attempts at representation — though he does not feel we’re beyond addressing representation — was criticality in its loving sense. “Love isn’t just about accepting things as they are. It’s about pushing back. And that’s something I try to keep at the centre of my work.” While for some the word ‘love’ may evoke passivity and sentimentality, Katki uses it in pursuit of an ethically rigorous commitment to his art-making, as a guardian of the histories that underpin his practice.

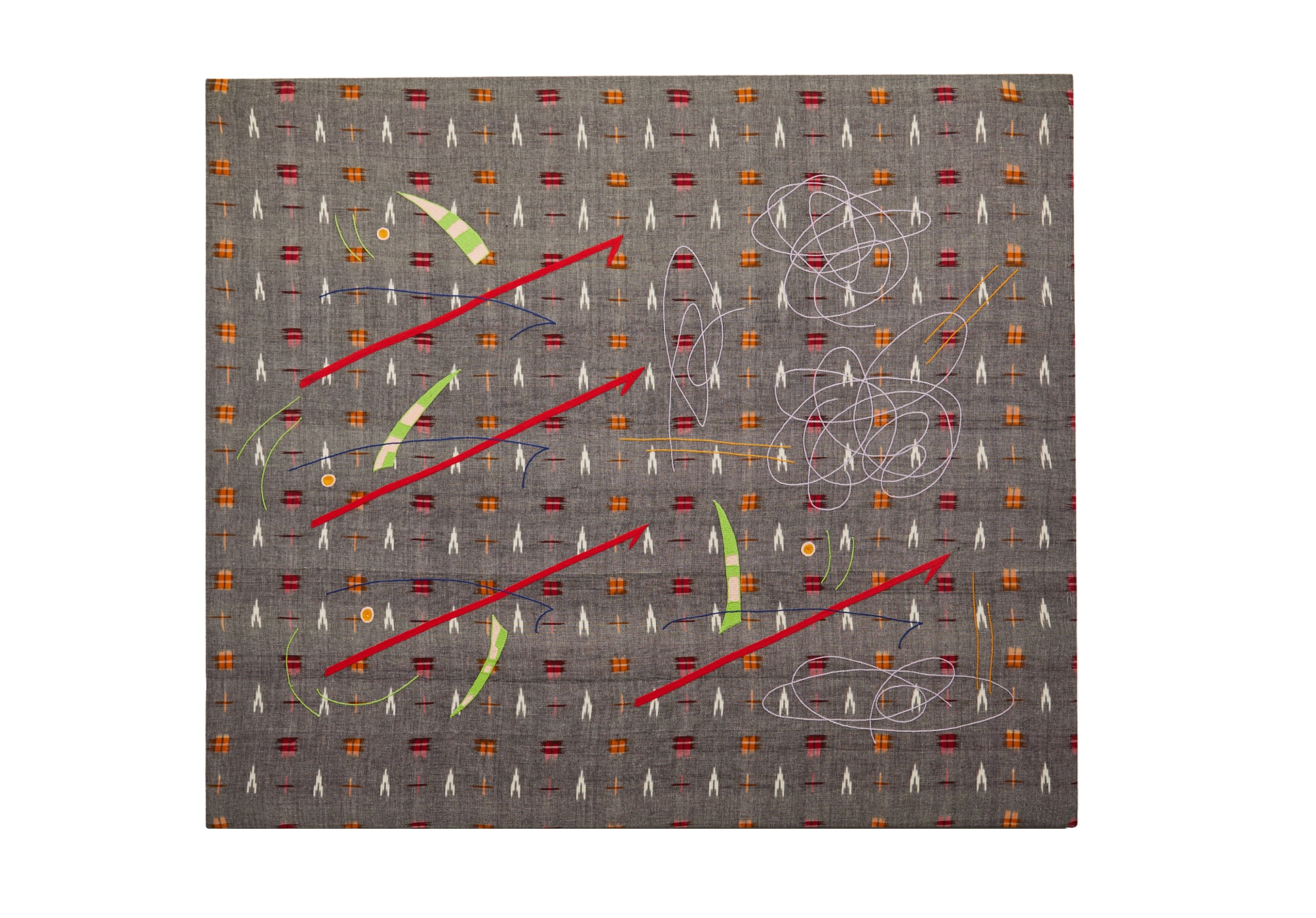

Part of this loving pushback has taken the form of a refusal to make work completely legible for prospective audiences. Vazhghān | Vocabulary, a solo exhibition presented in late 2024 at Tim Melville Gallery — one of the two dealer galleries which represent Katki in New Zealand — consisted of 13 embroideries on cloth. In an act of studied opacity, the works’ primary titles were rendered in Farsi, with an accompanying parenthetical in English which, instead of a directly translating, conveyed “affective associations” conjured by reading Forugh Farrokhzad’s poems, درس لصف زاغآ ھب میروایب نامیا / Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season.

Central to Vazhghān | Vocabulary was a collaboration with ‘M’, who had tailored the artist’s trousers for over a decade, and Katki’s maternal grandfather’s before him. At a small workshop in Tardeo, South Mumbai, M still produces simple garments for a range of local residents, despite the onset of globalisation and fast fashion. Somehow the practice of buying cloth and commissioning a tailor to make garments has endured, albeit on a smaller scale than in earlier decades.

Katki was drawn to the “distinct sensibility” and dress of Parsi residents in his neighbourhood — something that he and M delight in observing as they take M’s dog Ginger for walks. The subtle patterns (simple checks, pencil stripes) and colours (muted earth tones, pastels) form a sartorial code built on shared affinities among the Parsi ethnominority’s ageing and declining population. That the fabrics are almost always khadi — a handspun woven-fibre cloth associated with independence movements on the Indian subcontinent — adds a layer of complexity that nods to local history and politics.

Vazhghān | Vocabulary is also an informal community archive. Over the course of a year, M selectively saved scraps of cloth of at least a half-metre from his tailoring commissions. He and Katki then sat, every few weeks, with the bundle of textiles and discussed some compositional studies — usually drawings on paper — that Katki was thinking of embroidering on the offcut textiles. Together they decided where each might fit and in what context it felt appropriate, before Katki went off to execute the final pieces.

This year in Berlin, for the residency he is at present undertaking, Katki hopes to finish the framework for a novel. He is outlining the text’s structure through form and experimentation and a lot of note-taking. The artist has textile work in progress, and a new film — his first foray into moving images — in development. Yet even in this new medium, Katki builds on older research, long-gestating ideas and preoccupations, and forms developed in previous work.

In conversations with his former collaborators, attention to detail and sensitivity to materials come up frequently as Katki’s best-honed skills. Adwait Singh, a curator and writer who has collaborated with the artist on several occasions, speaks of the “smallest of methodological choices” that Katki makes and how they “gleam with rare significance”. And what is an artist’s role if not one of making, in their own idiosyncratic way, history and its materials gleam — with renewed import and potential? The past is always already shot through with the promise of an otherwise, of futures untold; this is why we need artists like Katki: queer world-makers, archivists and fabulists who are willing to stretch history’s fabric against its grain.