Aug 2, 2021 Schools

At the bottom of a gully, at the western edge of Dunedin’s poshest suburb, Māori Hill, Rhonda Bryant and two dozen other Māori language learners are gathering around white folding tables and asking each other, “Kei hea…?” (“Where is…”?) The students range from young professionals to retirees and each is, in education-speak, a “second-chance learner”. “Mum was a fluent speaker,” explains Bryant, who grew up in a home where English took precedence. “I’ve heard that people were amazed to hear Mum speaking te reo Māori because there were very few people in the south who were first-language speakers at the time.”

In the mid-19th century, te reo Māori was the chief language of politics, commerce and everyday life in New Zealand. Missionaries and merchants were, more often than not, fluent speakers. The early colonial governors and native secretaries also spoke the language, out of necessity. It would take at least another decade for immigrant Pākehā to overtake Māori in population and, with that demographic transformation, for English to displace the indigenous language as the country’s lingua franca.

In the intervening century, te reo Māori held out in the sawmills and shearing sheds where Māori made up a ma- jority of the workforce, on the marae and in homes in New Zealand’s rural pockets, from the Far North to the Urewera Valley. But in each succeeding generation, the proportion of native speakers declined. Until the 1980s — when language revivalists were forcing the government to establish kōhanga reo (language nests) and confirm Māori as an official language — fewer than one in five Māori were fluent speakers. Urbanisation, the movement from the rural pock- ets to cities and towns, and government policies meant fewer and fewer Māori were speaking their own language.

“Mum was part of the generation who were beaten for speaking their own language at school, so she had to learn English,” said Bryant. “By the time I was at school, those days were over, but more because the policy had worked and there was no one to punish because no one was speaking Māori.” In the 1970s and 80s many of the prominent language activists, like the actor Rawiri Paratene, were second-chance learners themselves, and fighting for a right they correctly saw they were being deprived of by government actions.

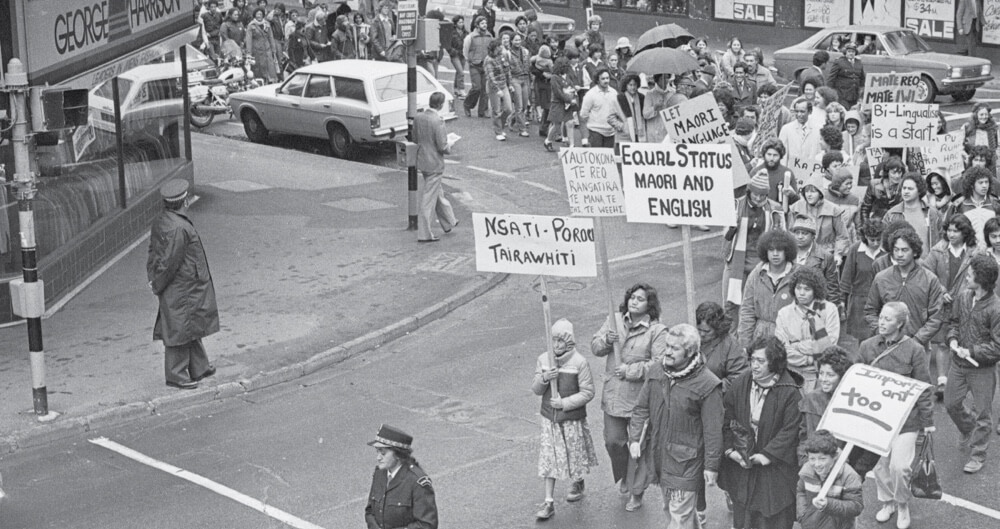

Demonstrators marching in Wellington during Maori Language Week, August 1980

But as the te reo Māori movement grew in force, with early leaders like Hana Te Hemara marching from the front, the Fourth Labour Government was forced into a corner: do nothing, and risk losing a chunk of their Māori voting base, or act, and perhaps risk losing what one might look back on as the redneck vote. Internal and external pressure meant the Government opted to act, relying heavily on their own reo speakers in caucus.

Come the Fifth Labour Government, the Crown was wholly committed to revitalisation. The late Parekura Horomia, as minister of Māori affairs, oversaw the introduction of Māori Television, renewed investment in Māori radio and encouraged attempts to build a Māori-speaking workforce using TeachNZ scholarships to funnel people fluent in te reo into teaching.

Yet almost two decades later, the language remains on the rocks. In a landmark study in 2020, “Kia kaua te reo e rite ki te moa, ka ngaro: do not let the language suffer the same fate as the moa”, five researchers from across New Zealand’s universities found that unless something is done, “with current learning rates, te reo Māori is on a pathway towards extinction”. Under Horomia and his prime minister, Helen Clark, the government’s focus was on building a Māori-speaking media ecosystem, one where fluent speakers could go to reinforce their language and where learners or newcomers could go to build their skills. This has seen adult learning go from strength to strength, the study’s authors found, but “school-age learning lags behind”.

Under the Sixth Labour Government, this is about to change. Education Minister Chris Hipkins, with Cabinet backing, is working to ensure that te reo Māori is “universally available” in New Zealand schools. “I think the preservation of te reo Māori is a Treaty of Waitangi issue,” he tells me. “It’s a taonga that we have a duty to preserve and promote” — a view the Waitangi Tribunal agrees with in its te reo Māori report. But, in what is a development from previous governments, Hipkins comes at the issue from an additional viewpoint. “Children who learn bilingually are better at their primary language. Through education, we can foster te reo Māori, encourage its uptake and preserve it, but in the process we can also improve teaching and learning in our schools.”

Studies in cognitive science find that second-language learning improves memory function, increases concentration spans and helps boost problem-solving and multitasking skills. In one famous study where participants were told to switch between categorising objects by colour (red and green) and categorising by shape (a circle or triangle), bilingual people could make the shift more quickly than monoglots, reflecting better cognitive control (or “executive function”) when changing tasks on the fly.

Increasingly, New Zealand schools are recognising these benefits. At King’s College, as one example, te reo Māori is compulsory in Years 9 and 10, and Rotorua Boys’ High School, as a slightly different example, integrates te reo Māori into its compulsory Māori performing arts course at Year 9 and compulsory tikanga course at Year 10. “When I was at primary and high school, te reo Māori was seen as ‘the Māori kids’ subject’,” Hipkins says. “It wasn’t an option we were encouraged to do, or indeed had the opportunity to do. But today, parents see their children learning a second language, and it hasn’t necessarily required a government directive; instead, it’s been happening organically, and those parents are increasingly seeing the benefit of that.”

Under the ambitious “Strategy for Māori Language Revitalisation 2019-2023” the Government is aiming to equip a million New Zealanders with the ability to speak basic te reo Māori by 2040. Part of reaching that goal is ensuring the language is universally available in schools, but as Hipkins acknowledges, “We have a workforce and capacity issue.” In short, there are too few teachers and too many keen learners. This means schools with deep pockets (King’s College) or those within large Māori-speaking communities (Rotorua Boys’ High) are often better equipped to offer te reo Māori.

To change that, the Government is making what is likely to be the largest investment in te reo Māori learning in New Zealand history. Te Ahu o te Reo Māori is one of those investments, taking the existing education work-force — whether Māori or non-Māori — and providing training to integrate te reo into student learning. The programme was successful in its pilot stage in 2019 and 2020 and will roll out to 10,000 participants each year for four years from this July. The programme will sit alongside investments in the te reo Māori curriculum and into training for fluent Māori speakers.

“It’s a lot easier to learn languages the younger you are,” says Hipkins. “When I go onto marae, I wish I had had the opportunity to learn Māori when it was easier [back in his schooldays].” But does the minister worry that integrating te reo Māori learning into all schools may lead to a backlash? “We’re entering an area where race is back on the agenda” — a gentle sledge directed at National Party leader Judith Collins — “but I’m hopeful we’ll move past that. Te reo Māori is our indigenous language, and it does make us truly unique.”

Come 2040, it’s expected that more that one million New Zealanders will agree.

—

This story was published in Metro 431 – Available here in print and pdf.