Jul 9, 2025 People

As usual, it starts with a single word typed into the search bar and fired into the ether. The word in question: ‘bakery’. Kua hoki 105 pūkete — 105 search results come back to me. The sifting begins. Black-and-white photographs of ovens and bowls and soldiers carrying wooden trays laden with bread. The 1st New Zealand Field Bakery, active on the Western Front from 1916 to 1919 — who knew? A plethora of pencils, badges and dioramas — the usual random assortment of museumy things that one is presented with when searching the vast and eclectic collections of my workplace, Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum.

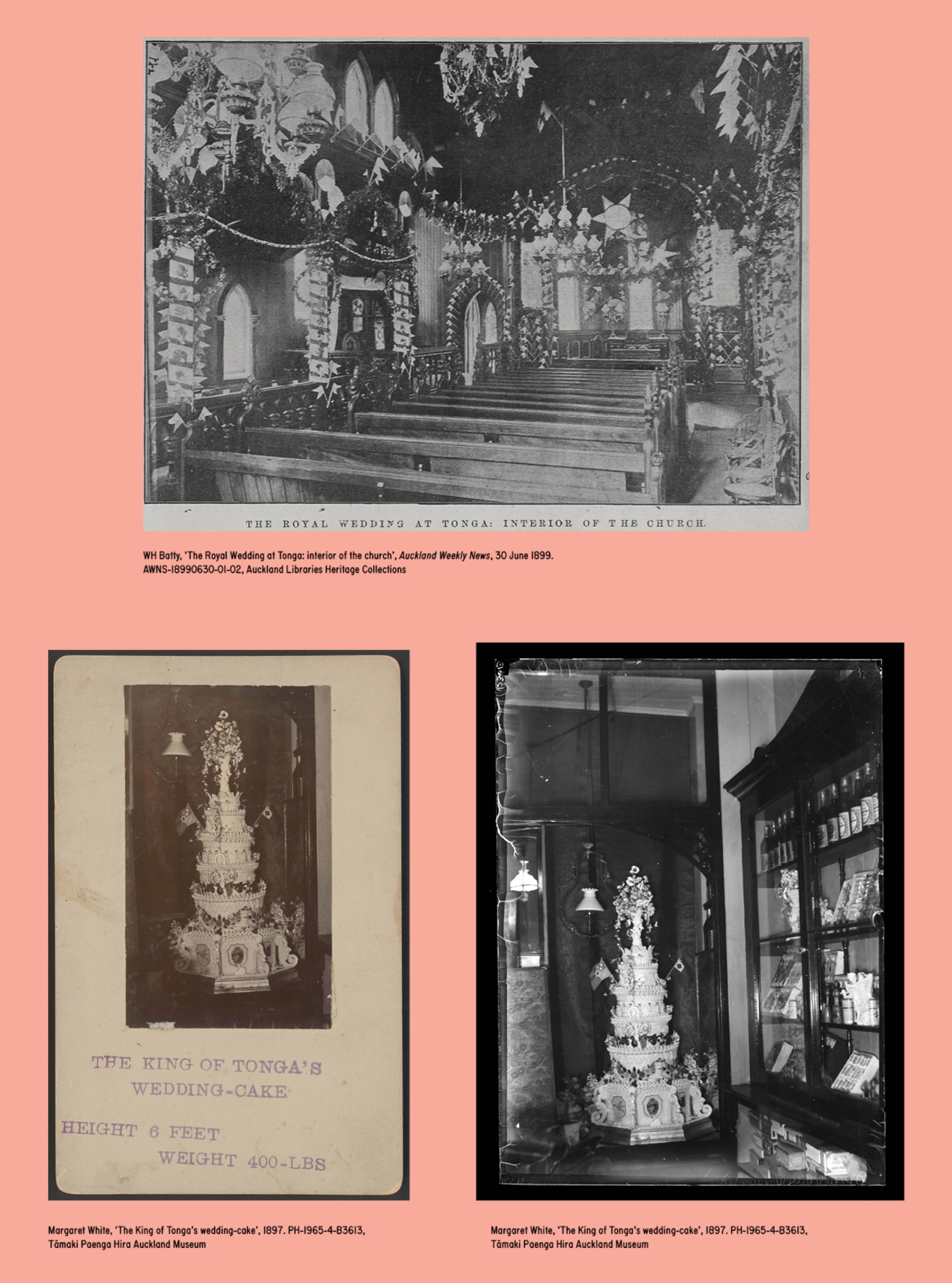

And then, there it is. I see it first as a little thumbnail image — a tall, white, decorative thing flanked by two smaller white decorative things. The text to one side states: “Cake for the wedding of King Siaosi Tupou II (George Tupou II) and Lavinia Veiongo Fotu.”

Then more text:

Photograph of three elaborately decorated cakes from Walter Buchanan’s Bakery on Karangahape Road.

The cake is decorated with the Tongan flag (right), Royal Standard of Tonga flag (left) and the Tongan Coat of Arms. The cake is embellished with flowers, swans, doves and figures. The cake is sat on a wooden plinth.

The cake is sat on a wooden plinth and it is extraordinary! The word “figures” in the description doesn’t do the creation justice. Circling one of the cake’s layers, there is what looks to be a bas-relief of dancing women holding hands, their arms extended skyward. Respectfully jubilant, they resemble those connected paper dolls that children cut out of paper. There are coloured fruits — grapes, apples, pears. There are cherubs. Decorative features protrude from the surface of the cake as if it were a Sienese cathedral — all glistening pastels and frothy figures. The peak of this six-layer construction is topped with a vase (is it edible?) and cascading floral arrangement. A cake fit for — and indeed intended for — a king. I will soon learn that it stood six feet tall and weighed 400 pounds.

I will also learn that this is not the tallest cake made by this particular baker, nor is it the only time he baked a wedding cake for the king of Tonga.

*

The year is 1897 and Walter Buchanan of Karangahape Rd has been commissioned to make — no, design, no… forge — a cake for the king of Tonga, the likes of which this country had never seen. Indeed, I imagine the bakery like a forgery — fiery ovens, specific tools, components being cast and set. The cake is displayed in the window of Buchanan’s bakery for a single day in late July 1897, then shipped to Tonga for the apparently pending nuptials. Shipped to Tonga. The large confectionery passenger and its two small sugary friends make their way up into the Pacific on board the SS Ovalau. Were they escorted by someone? Or did they embark on the ship alone, like children sent off to visit their grandparents?

Glowing reports of the cake appear in newspapers in Auckland and Buchanan’s native Scotland, to be carefully preserved in the newspaper archives of today. Curiously, though, no royal Tongan wedding eventuates in 1897 or 1898 — King Tupou did not marry Lavinia Veiongo Fotu until 1 June 1899. Digging around in the archives, I decide I must know more about this “monster cake” and what happened to it, about the bakery that constructed the “dazzling creation of sweet and daintily-conceived toothsomeness”, and about the baker who was entrusted to bring it forth.

*

Walter Buchanan arrived in Auckland in 1879 from Paisley, Scotland. After his schooling, he became an apprentice in his father’s bakery and then, as the reports say, decided to “strike out” on his own. The place he struck was Auckland. After working as a baker in the growing city for several years — exactly where, we do not know — in 1884 he took over the Queensland Bakery on Wakefield St, which had been opened several years prior by a Mr P Heath, who hailed, unsurprisingly, from Queensland.

From late 1884, ‘help wanted’ advertisements for the bakery began appearing in the Auckland newspapers. Buchanan recruited for a “baker (first hand)”, a “respectable general servant”, a “strong youth” — first tentative steps toward building a leavened empire. Over the next few years we see snippets of Buchanan’s life revealed in the pages of the Auckland Star and other newspapers: the birth of a daughter in 1888, a fire in 1886, an accident involving a horse cart in 1887. An 1891 application for consent to build a lean-to at the Wakefield St premises indicates that he was expanding. And expand he did. More staff were hired, new breads were created: the Patent Diastase Bread, the Wallace Ideal Air-raised Bread and the Fermented Pure Wheat-meal Bread. Buchanan’s reputation as a first-rate baker flourished — his bakery was proclaimed “one of the best known of its kind in Auckland”, beloved among the city’s housewives.

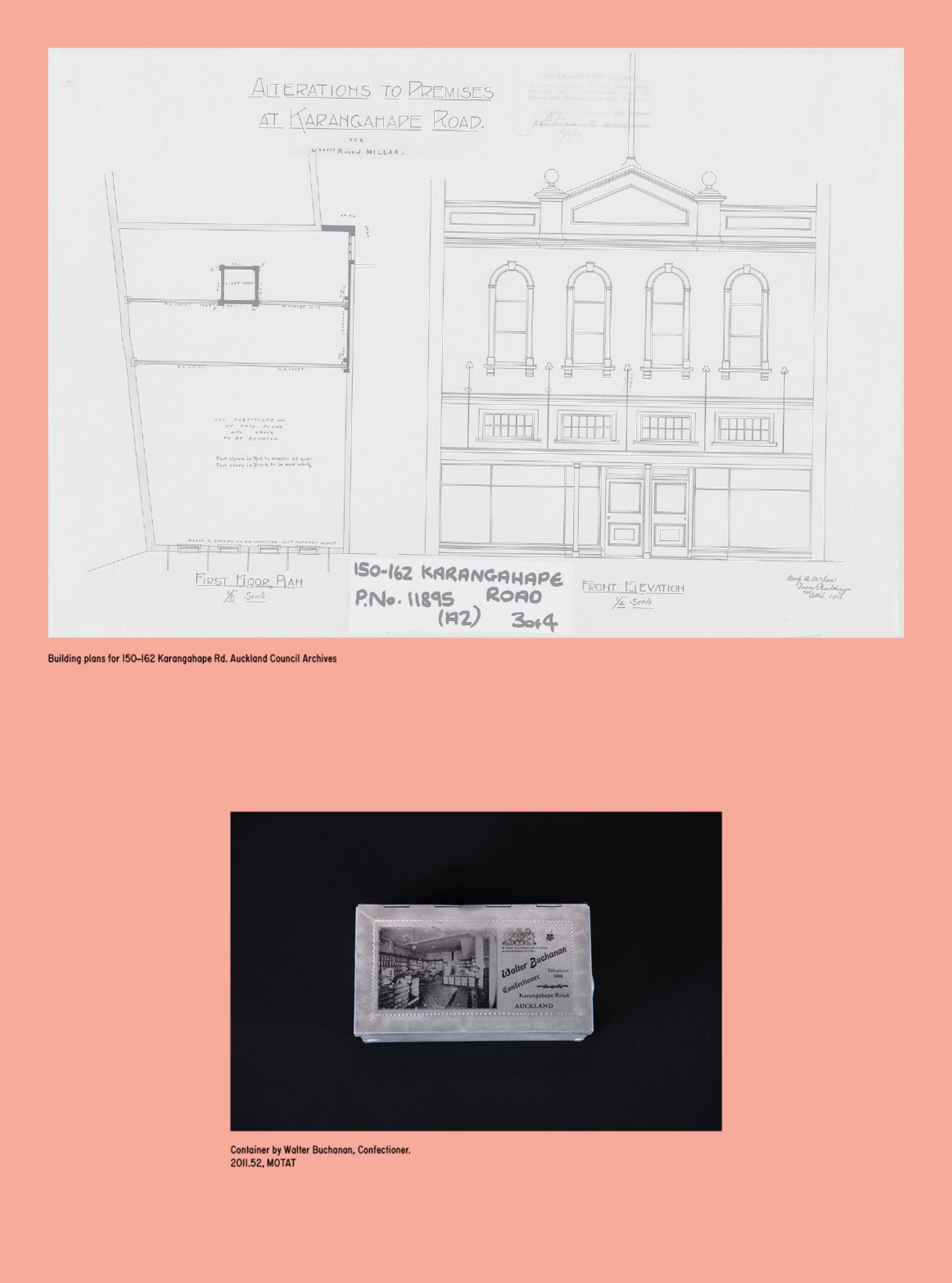

Buchanan’s ambitions eventually outgrew his Wakefield Street confines and by January 1897 he had moved to new premises on Karangahape Rd. We know this because another horse and cart accident befell our friend. A horse belonging to him upset a waggonette it was pulling, spilling the driver, and bolted from Symonds St along K Rd, creating mayhem along the way.

The year of the waggonette accident was also the year of the First Royal Cake.

There had been considerable scandal and upset around the marital plans of King Siaosi Tupou II of Tonga. In 1896, rumours circulated that he intended to marry Jane von Treskow, the daughter of German Vice-consul Waldemar von Treskow. In 1897, the king quietly ordered a cake and a wedding ring from Auckland, without announcing who his bride might be. When his plans became apparent, and given that Jane was not royal or of aristocratic birth, the marriage was rejected by Parliament. An article in the Wanganui Chronicle tells the curious tale of the cancelled royal wedding and an ornate wedding cake — “a triumph of the confectioner’s art, and evidently large enough and rich enough to disturb the digestion of the whole group for many moons” — nearly going to ruin in Tonga’s humid climate.

But it is a truth universally acknowledged that kings must marry and produce heirs, and in early 1899, there was renewed hope that wedding bells might soon ring for King Tupou. Would the deteriorating cake still be fit for purpose? Assuming that it was a fruitcake — which are traditional for weddings, and Buchanan was known for his Christmas versions — the underlying cake structure would have been well placed to endure. Fruitcakes are infamously long-lasting. As anyone who bakes them will know, they happily last months in a cake tin, especially if fed a steady diet of whisky. Astonishingly, the world’s oldest fruitcake, which resides in Michigan, was allegedly baked in 1878.

The tropical environment, however, must have been a challenge. In language that wouldn’t seem out of place in Miss Havisham’s household, the newspapers reported that Buchanan’s cake, “not being built to stand the ravages of the Tongan ants, nor the fierce heat of a tropical sun”, was becoming “small by degrees, and beautifully less”. With a suitable bride finally chosen and a wedding now imminent, the cake was apparently “docked for repairs”: “the icing is being restored to its pristine glory, and the gaps in the structure that have been eaten out by the ants are being plugged up”. Almost a full two years after its conception, display in Auckland and arrival in Tonga, Buchanan’s first royal wedding cake finally fulfilled its destiny.

*

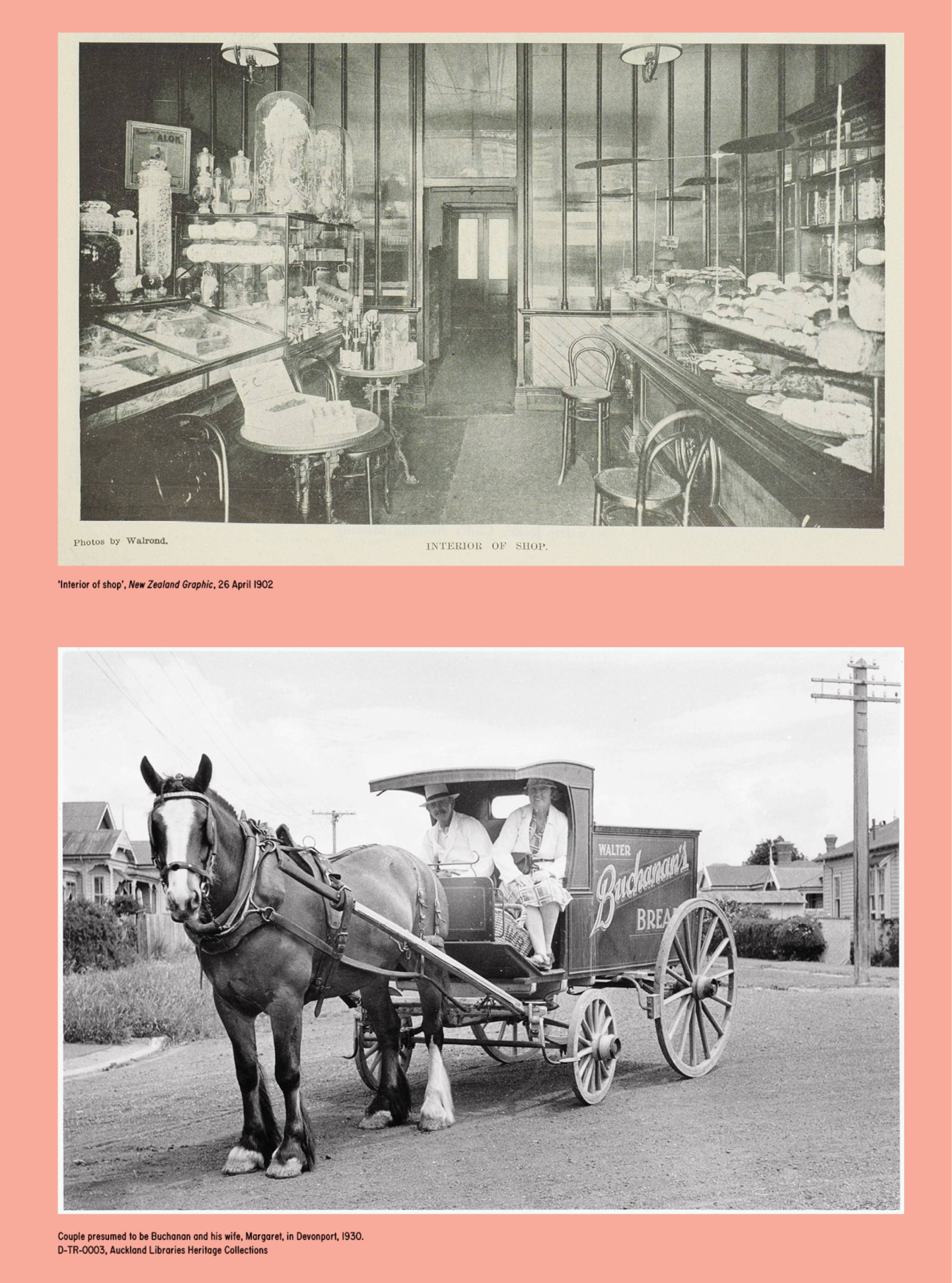

With such illustrious patronage and rapturous press, it is unsurprising that the operation Buchanan built at Karangahape Rd was of grand proportions. In 1902, the New Zealand Graphic ran a two-page illustrated feature on the business and its owner, showcasing the sumptuous storefront: glass cabinets laden with pastries; enormous glass jars filled with biscuits and other fancies; ornate cakes enclosed in terrarium-like bell jars. Did you think that those whirligig fans that spin around on cafe countertops protecting pastries from flies were a recent thing? Think again — in the feature, the right-hand counter top at Buchanan’s of K Rd boasts three large tabletop fans that loom over the baked goods like the wind turbines on the Tararua Ranges. The tearoom, where these goods may be consumed, is fitted out in “delicate green tones”. And moving through doors at the back of the shop, a visitor to the building would descend labyrinthine corridors to finally arrive at the engine room of the bakery: the bakehouse, where an army of bakers worked at the intersection of the past and the future.

In the early years of the 20th century, Buchanan’s goods were still made by hand, but the machine era was looming. In 1909, the business expanded and an Eden Terrace bakehouse was opened. The automated nature of the operation, now called Buchanan’s Model Bakery, was described at delighted length in the Auckland Star. Chutes there sent flour careering down to meet an automated sifter and on to an automated kneading machine. “From first to last the dough is hardly ever touched by human hands,” marvelled the visiting journalist, adding that “cleanliness and labour saving” was the name of the game.

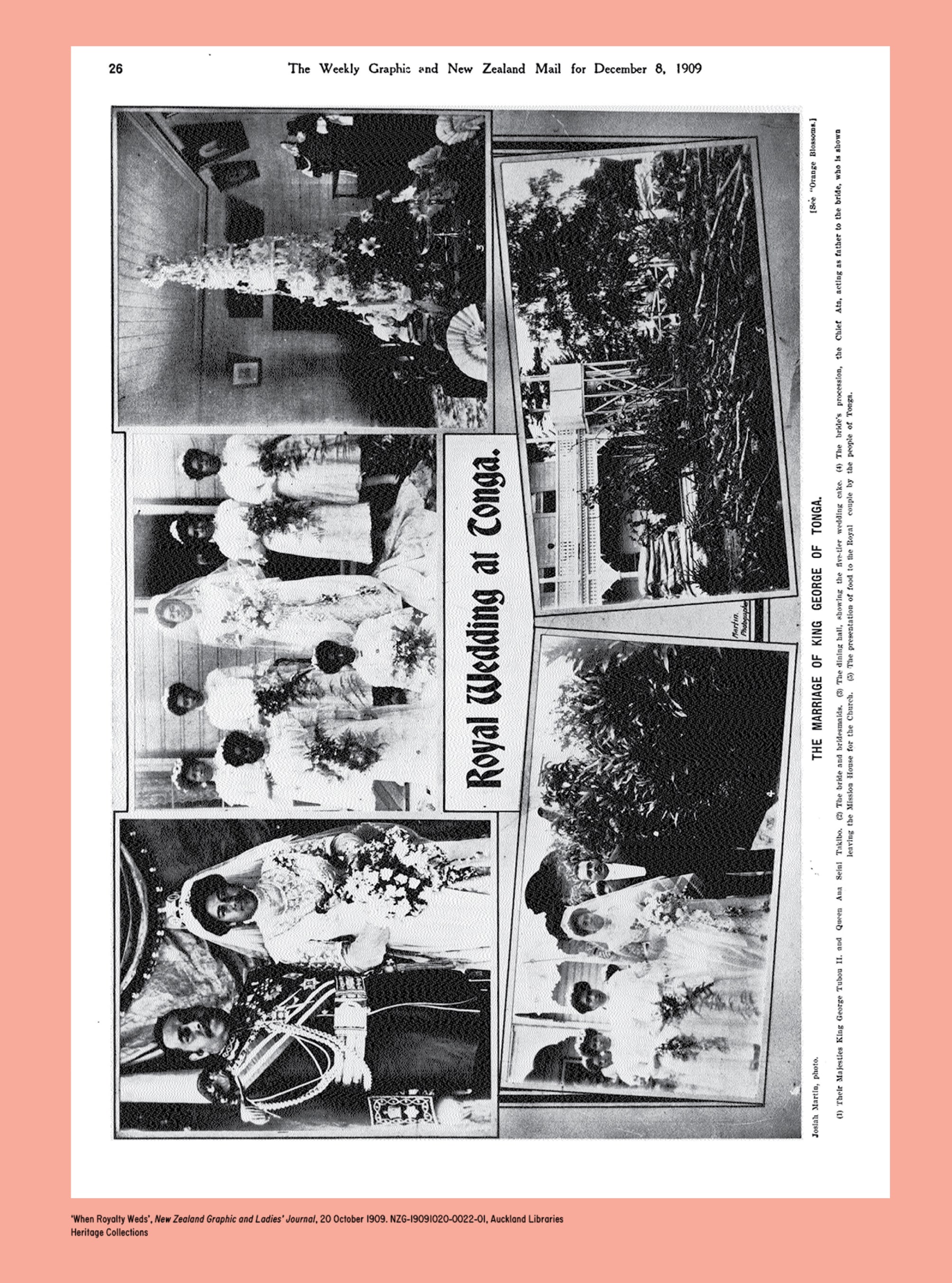

Also in 1909, Buchanan creates a second wedding cake for King Tupou II, whose first wife, Lavinia, had died in 1902 of tuberculosis, after bearing one daughter, Sālote. This second marriage was to ʻAnaseini Takipō Afuhaʻamango, a sixteen-year-old from a high-ranking chiefly family. I am intrigued by this repeat custom — and indeed how Buchanan was bestowed this royal favour in the first place.

It is possible that the king had actually met Buchanan: before he ascended the throne in 1893, Tupou had briefly lived in Auckland, around 1890. A newspaper article from the time of the first cake confidently states that he attended Auckland Grammar School and while here “became very friendly with Mr Buchanan”. This is possible, but there is other evidence to suggest that Tupou was privately tutored by Charles Douglas Whitcombe — a secretary to Sir George Grey and an adviser to the Tongan government — for the six months or so that he was in Auckland. Regardless, perhaps the prince encountered and sampled Buchanan’s delicacies at one of the many “Tea Meetings, Socials, Picnics, Balls” he catered for Auckland’s beau monde. We can only imagine.

Back to the wedding. According to reports, the second cake was even larger than the first, standing at a full eight feet tall and weighing an extraordinary 500 pounds. I ask my colleague Wanda Ieremia-Allan, the museum’s Pacific documentary heritage curator, about cake traditions in Pacific wedding ceremonies. She emails back:

Decorated Pacific wedding cakes illustrate the adoption of Victorian mores into Pacific reciprocal ceremony. The 19th-century missionisation of the Pacific, with its emphasis on monogamous Christian marriages, saw these practices first adopted by high-ranking chiefly families.

Large and ornate wedding cakes therefore reflected the wealth and status of both families. The top tiers served as decorative additions to traditional gifts of roasted pigs, taro, yams, ngatu/siapo (tapa) and ie toga (fine mats) given to high-ranking guests.

Guests, representing many connections, often numbered in their hundreds, so the bottom layer had to be sufficiently large to be served to everyone in attendance. The blessing and consumption of a piece of cake by each guest sanctioned the union of the two families. Members of the bride’s wedding party were tasked with the animated distribution of the cake which added to the vibrant and spectacular ceremony.

King Tupou’s second cake, a “revelation in the art of building wedding cakes”, according to the Auckland Star, was emblazoned with the initials of the monarch and his bride-to-be. Once again, it was displayed in the window of the bakery — though reportedly the initials of the bride were covered, to keep her identity secret until the wedding day.

With the only child of the king’s first marriage a daughter, the chiefly families of Tonga hoped that this second marriage would produce a male heir. Instead, Queen Takipō gave birth to two further daughters. When the king died in 1918, his oldest daughter, who had been exiled in Auckland since the second marriage in 1909, became Queen Sālote Tupou III, the first queen regnant of Tonga. Much loved by her people, Queen Sālote ruled for nearly 48 years.

*

Despite the good press Buchanan generally received, scandal visited him at various points in his rather public life. His name and that of his business appear more than once in newspaper court pages. Buchanan’s first brush with the law was in 1895, for contravening the Factory Act — a piece of legislation that had been introduced in 1891 to regulate factories and improve working conditions. Buchanan had been discovered keeping three teenage employees working on a Saturday for longer than the law stipulated and was fined three pounds, plus legal costs, for this breach.

Buchanan tried to defend himself, saying he “always treated his employees as fairly as he could”, but the Crown solicitor called his actions a “scandalous evasion” of the Factory Act. Even more egregiously, he had fired two of the workers after the charges were laid.

In essence, it appears that Buchanan was a pragmatic and hard-nosed businessman. He was a stalwart member of the Master Bakers of Auckland — a conglomerate of business owners who seem to have been primarily dedicated to discussing and setting the price of bread. Certainly the members of this guild may not have always been the good guys: they had regular spats with the Bakers Union over wages, working conditions and hours.

So what happened to Buchanan’s bakery? What came of the cakes, the bonbons and other sugary triumphs that had propelled our Scotsman into the orbit of royalty? Sadly, the cake side of the business failed its final proof. Around 1912, Buchanan sold it to a syndicate of buyers, who promptly ran it into the ground — by the end of 1914, the Walter Buchanan Cake Company was in liquidation.

Buchanan had continued in a role of general supervision, as well as helping with the delivery of “fancy goods”, but the business was run day to day by managers who, in Buchanan’s opinion, squandered profits and mismanaged funds, giving customers “too much value for money”. When the company failed, the accusations of mismanagement were raked over in the press. One article was dramatically titled “Banquets For Sixpence: How Local Cake Company Came To Grief”. In another, an account of the bankruptcy proceedings, it was noted, “Once, when the manager was complaining that he could not afford some new carpet for the shops, he, Mr. Buchanan, had an overweight jam-roll in his hand, and pointed out that if the company would save 25 per cent of the roll it would be able to pay for the carpet and show a dividend as well.”

Was the overfilled jam-roll the avocado toast of the early 20th century, bringing the spendthrift managers to grief? Perhaps. The savvy Buchanan clearly knew what he was doing. The bread side of the business, remaining in his hands, continued to boom. By 1919, Buchanan’s Eden Terrace operation “was the most modern bread-working plant in New Zealand, with only two other similar bakeries in Australasia. Each oven had capacity for 280 loaves, so, with six ovens, Buchanan’s bakery was capable of baking 10,000 loaves in 8 hours.”

Walter Buchanan Ltd, as the company was officially known, operated until at least 1960, going through various ups and downs. The company’s penchant for being technologically advanced didn’t always pay off. In 1930, the acquisition of new ovens backfired when the freshly installed machines overheated, burning and destroying nearly 2000 loaves of bread. Buchanan — who remained active in the business until 1941, leaving him only three years of retirement before his death in March 1944 — would have been none too pleased. And perhaps it was as well that he didn’t live to see the company taken to court in 1950, alongside another bakery, for selling bread “unfit for human consumption”. The loaves were found to contain mouse droppings. I suppose it can’t all be royal weddings and triumphant press.

Former mayor of Waitākere and regular Metro contributor Sir Bob Harvey was employed at Buchanan’s as a lad. “I would work there with my uncles,” he recalls, “for half a crown on Sunday nights from 7 till 9pm, when the hot dough would be turned into loaves on the first floor and then come sliding down chutes to be taken out of the tins and put on to trays for us boys to push out into the cooling yards for delivery the next morning.”

At some point, the bakery in Eden Terrace was taken over by another bakery empire, Findlay’s, which had begun life in Gisborne in 1913. Then in 1989, the bakery building was bought by the Auckland Indian Association, and is now known as the Mahatma Gandhi Centre. “The interior is still much the same as it was back then,” notes Sir Bob.

And that’s how it goes. Buildings take on personas as if slipping on a new coat. Streets get paved over. Memories fade. But our city, like all cities, is a palimpsest and even if obscured, she still wears her histories if you choose to look. A Tongan monarch. A Scottish baker. A search on a museum database 128 years later and suddenly a little corner of history comes into focus. I can almost smell the cakes in the oven.