Oct 24, 2023 Crime

On February 14th 1992 two workmen taking a pee off the road at Keith Hay Park Mt Roskill found to their horror a body of a 12 year old Samoan girl, half naked, lying face down in a muddy ditch. Her clothes were scattered and someone would later find her bra twisted in the nearby public toilets. She was a runaway who had been missing for four days and the police were not interested. She wasn’t white or rich and they concluded she wasn’t a victim. But she was. Someone had killed her. But who?

This was a story that Metro wanted to uncover and it would take time and painstaking research and interviews around Agnes and her life on the run. 12 year old Agnes was a twin and although everyone touched by the story suspected foul play, the coroner’s report was simply that she had drowned. Case closed. But Carol Du Chateau, one of Metro’s award winning journalists decided to find out where the clues were and she wasn’t giving up. This is a superb piece of investigative journalism which brought the story into the spotlight and helped reopen the case in 1996. It remains unsolved.

Bob Harvey

Archivist

–

Agnes Ali’iva’a was just 12 when she died her lonely death. For three days no-one came forward to identify her body. Then, when someone did, we learned that she was Samoan, a twin, a runaway, and that her mother – who suspected foul play was unhappy with the coroner’s eventual verdict that she had drowned. And then nothing. The police closed her file, as they often do with runaways. The Department of Social/ Welfare, which had been involved in Agnes’s life, remained silent after her death. Not even the Sunday papers picked up the story. It was as though she had never existed. Ask yourself, what would have happened if she’d been white? If she’d been middle class? If she’d been your daughter? CARROLL DU CHATEAU has asked.

Friday February 14 is the kind of depressing day when rain threatens but never arrives. At 7.30 am groundsman Andrew Webb, 26, is about to make his first comfort stop for the morning. With his mate, Shane Fyfe, he crosses Keith Hay Park, where it backs onto Mount Roskill Grammar run-down houses and small factories and heads for the toilet block tagged with graffiti by local kids.

The two men don’t see the drain until they are almost in it. Four metres deep and steep-sided, these ditches which run through to the Manukau Harbour are unsignposted and unfenced. “We didn’t know there was a drain there,” Webb says. “We walked right up to it, and there she was. At first we thought she was a guy. She was white and face down in the water.”

Leaving his mate guarding the body which was spread-eagled in a half-metre of water, Webb ran to a nearby panel beating firm and called the Auckland Central police station. “The cops asked me to stay with it [the body] and keep everyone away. I waited there for half an hour until they arrived. Later, Shane found her top all knotted up by the toilets. It was a grey running top, bra-type thing. We told one of the cops, but he didn’t seem very interested, so Shane left it by the toilets and no one went to get it.”

The police team from Avondale headed by Detective Inspector Mike Crawford and Detective Sergeant John “Fingers” Flanagan, his 21C, will turn the body over and discover that this is no pakeha man but a young Pacific Island woman aged-they decide by the size of her breasts – between 18 and 23.

They will also decide that despite the fact that the girl was half clothed, she had died as the result of an accident, that she fell into a ditch rather than was pushed or thrown. “You’ve got to get the full feeling of this drain”, explains Crawford “It was dark, and there was no street lighting. It was like the black hole of Calcutta”.

The pathologist, Dr Timothy Koelmeyer will examine the body at Auckland Hospital mortuary and will also estimate the woman was in her late teens or early 20s. Even though it will not appear in his final report, he will also tell police that although there was no semen present when he examined her, the young woman had been sexually active for some time. Among the scratches and bruises consistent with falling out of a moving car and into a four-metre ditch, he will notice a 14 centimetre abrasion over her shoulder, from the lower left side of her neck to the nape of her neck, and a similar 19 centimetre abrasion extending in a corresponding fashion over the right shoulder region which he will say may have been caused by a jacket with ties around the neck.

On the evening of the third day someone will recognise the bloated face staring out of the Herald as 12 year old Agnes Ali’iva’a. He is a former pastor of a Samoan church. His name and some others have had to be removed from this story for legal reasons which will soon become obvious.

Over the next two weeks Flanagan and his team will piece together the events that led to Agnes’s death. They will discover that she was a twin, lived in Alford Street, Waterview, and was known by several names – GrenneII (the name of her mother’s first husband), Ali’iva’a (possibly that of her own missing father), [ ….. ] (that of her present stepfather), Bignall (the name she used occasionally herself) and Mia’ava (a total mystery). As Mike Crawford says “There were half a dozen fathers for half a dozen kids. For this story we’II call her Ali’iva’a.

On Thursday, February 13 Agnes had had an argument with her mother, Sanitoa, commonly known as Sunny. For months now she’d refused to go back to Balmoral Intermediate (which the twins had been attending for reasons we shall come to) and Sunny, overstressed because her own mother was dying, went next door to phone the twins’ Social Welfare officer, Theresa Fepulea’i, at Henderson for help.

Agnes went straight to her bedroom brushed her hair into a neat ponytail, changed into the outfit she always wore when she went out – black sports bra, black hooded top, red track pants, boot style running shoes, asked her mother if she could go to a volleyball game at their Samoan church and took off up Alford Street and into the Great North Road towards New Lynn.

Four hours later at around 8.15pm, Lionel Devaliant, deputy principal of Green Bay High School, came out of a police community meeting at the New Lynn Community Centre and saw a young stony-faced Samoan girl emerge from the shadows of the Trans Cafe clutching a bus ticket: “I missed the bus. Can I have a ride to the Mount Roskill shops?” she asked him politely.

“There was something about her which bothered me,” says the 55 year old Devaliant who is familiar with Pacific Island youngsters after working for 14 years at Nga Tapuwae College in Mangere. “She wasn’t crying but she was definitely upset.

“It was getting dark, New Lynn’s got a bad name for crime, I’ve got four daughters myself. All these things went through my mind. She was well dressed; I knew she wasn’t a street kid because she was too clean, and she hadn’t been sniffing. But she was clearly uptight about something. Mount Roskill is on my way home … So I said, ‘Fine, I’ll take you to the disco [she’d changed her mind and decided she wanted to go to a school disco by then] providing I take you in and deliver you to a teacher.’”

When he arrived at Balmoral Intermediate in Brixton Road, Devaliant became even more suspicious. “There were no lights on,” he remembers. “She changed her story and told me she wanted to go to her uncle’s place next door. Then she said that she didn’t want to go to her uncle’s.

“I told her I didn’t believe her and was taking her to the nearest police station. She got the door open going down Dominion Road. I was trying to hold her but I sort of gave up when I had to slow down at the Balmoral traffic lights.”

It was between 8.30 and 9pm when John Duncan, who was working the night shift at Drivers Service Station on the corner of Dominion and Mt Albert Roads, saw Lionel Devaliant’s Sentra slow down and a dark-haired girl with tears in her eyes jump out, fall backwards into the gutter, then start running towards the garage and disappear into the darkness.

Only a few minutes later, lro Boaza, a 10-year-old Cook Island schoolmate of Agnes, saw her walking along the road while he and his dad were at the Chinese takeaway bar next to the TAB on Dominion Road. “I said ‘hi’ to Agnes and she said ‘hi’ back,” he told her sister Annie the next morning at school.

And then nothing. The next time Agnes was seen she was little more than a kilometre away in Keith Hay Park lying half naked at bottom of an open drain with froth in her nostrils, a four-centimetre bruise on her head and stiff with rigor mortis.

Let’s go back to the inner western suburbs, because the inner west is where the story begins. Over the past 10 years, as immigrants have gradually been squeezed from the inner city by gentrification and rising rents, many Samoans have moved into Waterview, Avondale and New Lynn. You see them at the Avondale racecourse market early on Sunday mornings loaded with delicious-looking Samoan doughnuts, fresh whole fish, veges, dirt-cheap clothes. You see the enormous number of Island churches, the greengrocers selling taro and green bananas.

This was Agnes Ali’iva’a’s world: a world where the church is all-important; when cousins and uncles and their babies move in and stay for months; where sex happens all the time, but is never talked about, where hidings and violence are part of the culture and frequent; and where it is not uncommon for children to be sent off to live with aunts and uncles or even the pastor when they need straightening out or the house gets too crowded.

The house where Agnes lived is owned by the Housing Corporation; several of the windows are boarded up; there’s an orange and green primed Holden Kingswood under the makeshift carport, a rusty yellow Cortina behind that and an ancient Morris 1100 parked on the lawn. Very often Sonny’s new husband (she married him only weeks after Agnes’s death), is to be found tinkering away under the bonnet. The back yard is guarded by a silent Rottweiler.

Sunny Ali’iva’a arrived from Savai’i in Western Samoa when she was 23. The streets of Auckland seemed paved with gold, a place where you could get a job for the asking, enjoy a life infinitely more luxurious than in Samoa and still make enough money to send some home. It was 1973, a time when unskilled immigrants were encouraged, and she soon settled in as a process worker at Alex Harvey Industries in Mount Wellington. Within a year Sunny married a New Zealander, Mr Grennell, a welder, with whom she had two children: Irene (now 19) and Wiki (now 17). But Grennell was looking for new horizons too and just after Wiki was born he headed for Australia. Then, when she was working on a machine at the Lundia factory in Carbine Road, Sunny had an accident that tore away most of her right knuckle. She has not worked since.

One night, after a one-night stand at a party, she became pregnant with Agnes and Annie who were born on April 25 1979.

“Who helped me?” she smiles. “No one. Just myself. In 1981 I met [ …. ] He’s 42 now and I’m 43 and we’ve got four children. My husband’s on the benefit at the moment — he’s still looking for a job. He’s a salesman and a process worker. Irene lives here with her daughter, Toni who’s 15 months and baby Dion who’s two months old … Irene’s on the DPB too. She’s going to shift to her new house soon — it’s near here, in Avondale, a Housing Corporation house too. She left school when she was 15. No, she didn’t work before she got pregnant.

“Why don’t I go back to Samoa? That’s what I’m thinking myself. Everything is very hard here for the money. But the kids are too young – they’re not used to island weather. I found out myself. I go back when Irene was small and the kids were pretty sick. Besides, there’s the money — it’s about $900 one way. I think I’ll stay here till the childrens are grown up.”

Sunny’s painstaking efforts to make this impoverished house cosy are heroic. There’s a brightly fringed mat on the door and a double inner-spring mattress, a picture of the Virgin and Child “O Come Let Us Adore Him” on one wall and a three dimensional rendition of the Crucifixion where the mourners move when you move your head. A plaque near the window asserts: “If you love someone let them go …” There’s also a huge TV set complete with video and Sky monitor pumping out the morning aerobics class.

In pride of place is a framed photo of Agnes and Annie, beaming in their Balmoral Intermediate netball uniforms. Agnes is bigger than her twin sister. They’re both good looking and well groomed.

The week of February 13 was a particularly tough one for the family. Sunny’s mother, who joined the rest of the family in New Zealand three years ago was in the terminal stages of cancer. “I took Mum to Mangere for some Samoan massage on the Thursday,” she remembers.

Then Agnes took off again. Sunny tells me: “I came back with Mum and Agnes is still not home. On Friday morning she’s still not home. I spent the whole weekend with Mum in hospital. Monday, at half past three, Mum passed away. At five o’clock in the afternoon we came home and at eight o’clock that Monday night there was a big knock on the door and there’s the pastor and his wife.

“I was really surprised when I saw him at the door and I saw he was crying and he said, “We came here to see about Agnes”. He had seen the newspaper photo and was sure it was Agnes. I straight away rang the police and they came that night and I went with my brother and he went in there to see her (it was around 3am), and then he said, ‘Yes, it’s Agnes.’ So we came home and had two funerals. And all the time I was in hospital with Mum I didn’t know Agnes was dead before Mum.”

Four days later, lovingly dressed m a white wedding gown with a white beaded cap over her shining hair, Agnes lay beside her grandmother in an open coffin while her family wept and mourned. All the care that was not lavished on her in life was there in death.

In Samoan culture the church is the societal anchor point. Church is where the children go for Sunday School, sport and fun. Their parents go for the music, spiritual solace, companionship and guidance — especially from their minister. Often there is an almost child-like faith in the pastor. Most families, as well as sending money back to Samoa, pay a title towards his upkeep.

In the inner west there are dozens of Pacific Island churches. The church in this story seems to have one of the smallest and poorest congregations. About 20 people with their hands outstretched above their heads, their faces uplifted, sing their hearts out. Hallelujah.

When, in 1990, a pastor and his wife offered to take over her feisty 10-year-old twins for a while to straighten them out, Sunny was overjoyed. “They both fight, they don’t listen to the teacher,” she explains, “So the pastor just came and said I was having a hard time with them and offered to help. He and his wife take them and teach them the church way. He had a big five-bedroomed house.”

What Sunny doesn’t mention is that the Department of Social Welfare was also involved, although for legal reasons the reasons for its involvement also cannot be set out here.

When I call on the pastor the young woman who wrenches his door open is wearing a T-shirt saying, “How to put on a condom”. She whispers at his door, fast and urgent, till she gets a grunt, says something in Samoan, then tells me he’s coming. It’s at least five minutes before a youngish man invites me into the threadbare hall, with its dangling naked light bulb, chipped paintwork and chair, to wait “[ …. ] is probably praying …. “he tells me.

[ ….. ] arrives dressed in grey pants with a powder-blue, fluffy-lined, hooded anorak. The kind of thing you’d expect on a little girl. His wife, a big woman and heavily pregnant, seems to find it hard to sit on the straight-backed chair and rubs her head scowling. “I was going to say that we don’t want to talk any more about Agnes. We don’t want to say her name again,” she says. “But we really love Agnes.”

The pastor hasn’t been working as a minister for the past year. He tells me it was his idea to stop preaching until “things died down” and that he now drives a taxi.

When I check with the taxi company manager he tells me the pastor only ever drove a cab for two weeks — “He’s a missionary you know.”

[ ….. ] also takes Samoan lodgers, mostly new immigrants (”we had 20 before but there’s only 10 now”) to help them get used to life in New Zealand. Most are unemployed (”only one of them is working, they try to get permits), their English is faltering and prayer and the church are clearly the most important part of their lives. When I leave, the soft-faced man who fetched the pastor for me is standing by the gate crooning a hymn, waiting for him to take him to church.

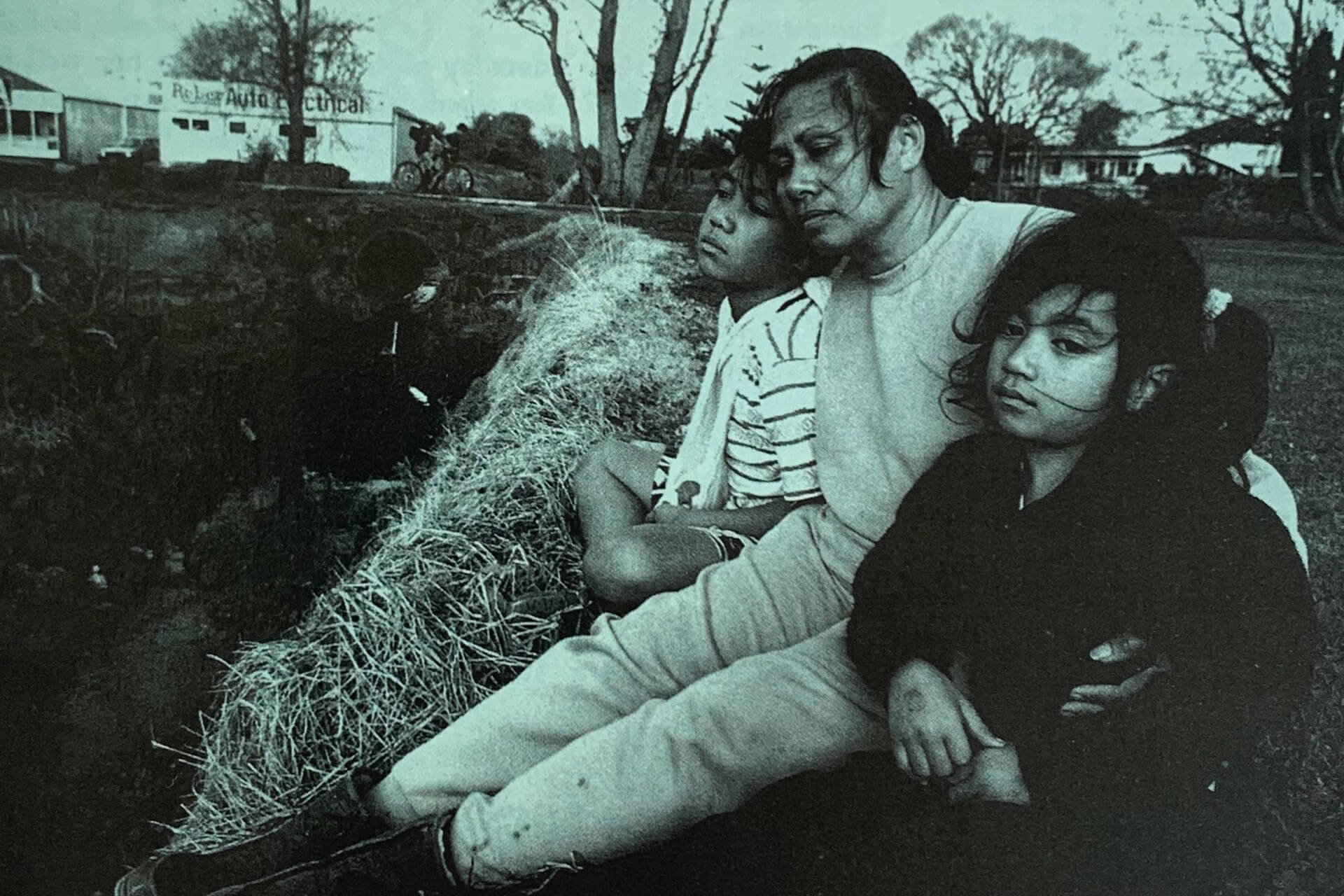

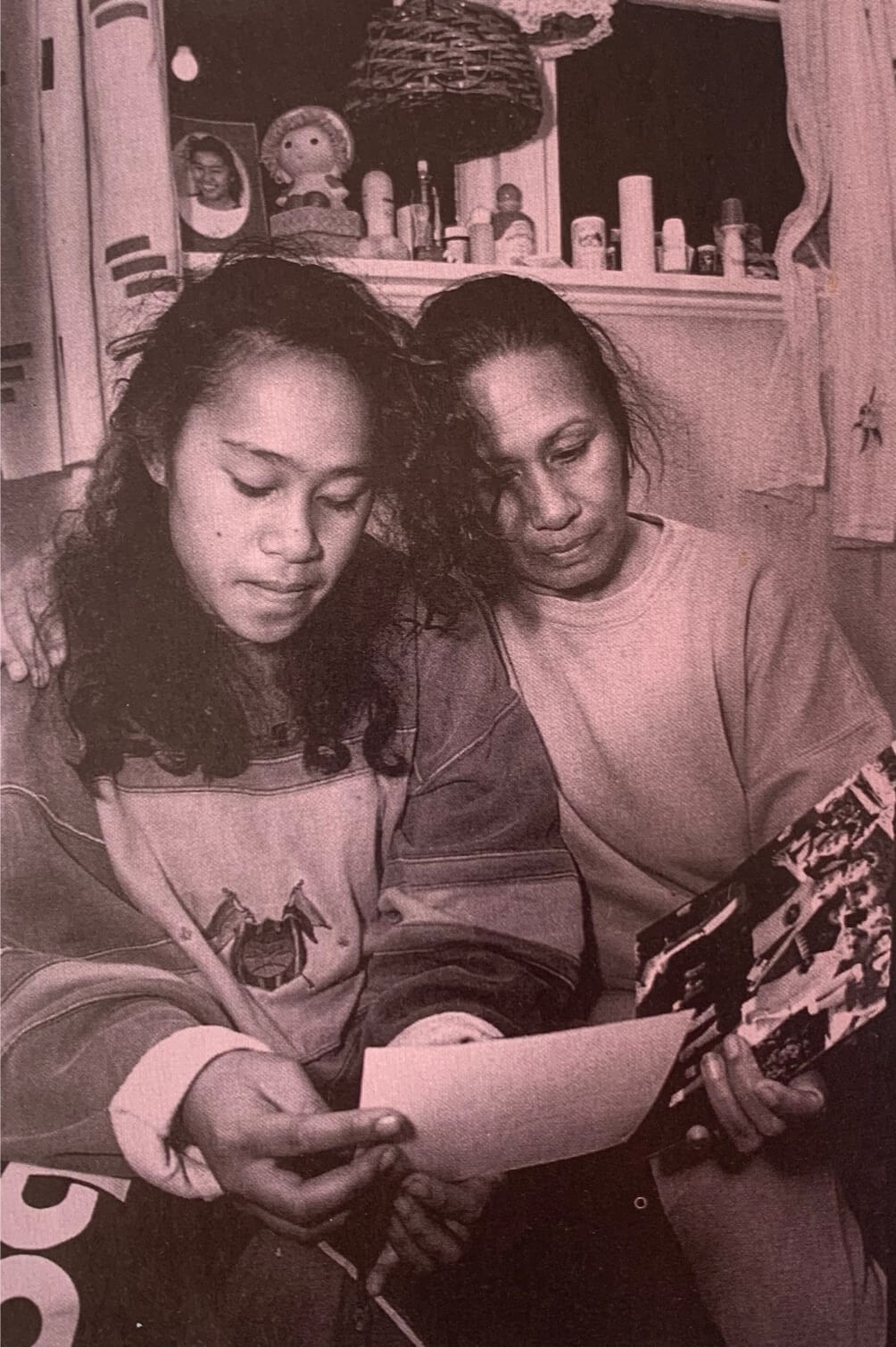

Sunny, right, with Agnes’ surviving twin, Annie

For a while after the twins moved in with the pastor, everything went smoothly. Except for a massive rumble two days after they started at Balmoral Intermediate, when Agnes and Annie took on some of the other Pacific Island kids in the playground, they fitted in well. They were 11, both in the form one netball team. Agnes’s work especially was excellent.

Claire Kirkman, her form teacher, describes Agnes as a conscientious pupil “She expressed herself very well,” she says. “Her co-ordination and physical skills were superb. She loved playing volleyball. That’s why I find it hard to imagine how she fell into a drain.”

From the beginning, both Kirkman and Jamee Anderson, the school principal, found Agnes’s relationship with her new guardian alarming. “He always brought Agnes to school and he’d wait round by the office and classroom,” says Anderson. “I’ve taught for 20 years and to me it just didn’t feel right, so I told Claire to keep a dossier”.

“A few weeks later,” Kirkman explains, her sister told one of the other teachers that Agnes was sleeping with her guardian. At that stage Agnes was blossoming. More often than not [ …. ] came to school with her and hung around. When I saw them together I could tell they were physically involved. Actually, you could be fairly naive and still notice. At one stage one of the other teachers mentioned their body language together to me.”

But by June, Agnes’s bloom was wearing thin. “She became tense and anxious and a little withdrawn,” says Kirkman. “Then we had a pubertal change health lesson where the children are encouraged to ask questions about their bodies and sex, and Agnes made some incredibly revealing comments. Things like: ‘When you’ve slept with someone and wake up in the morning the sheets are all sticky’ and ‘If you miss one period, could you be pregnant?’”

For Janice Anderson, who’d long been involved with adolescents, the warning lights were well and truly flashing, when, on July 15th, a letter was discovered in Agnes’s desk.

It began: “Dear [ ……… ], [ …. ] I am very sorry and please forgive me and I still love you as my father. “I cried every rime because I don’t know how to take my mind of you …. “

With something concrete to act on, the school authorities called in Social Welfare. “I spoke to Sue Lytollis at DSW Royal Oak … then Liz Grove took over,” says Anderson. “She said it would be reported to the sexual abuse team at the central police.”

The interview between Agnes and DSW took place on July 17 1991 in Janice Anderson’s office. Finally, hesitating and stricken with guilt, Agnes told her story.

Janice Anderson: “She acknowledged the sexual abuse and then Vailama, the social worker, asked me to leave and spoke to Agnes in Samoan.”

Although they never got what they term an “evidential” – a confession on video which means they could charge [ …. ], Social Welfare removed the girls from his care and, because [ …….. ] was living with their mother, placed them well away from Waterview. Annie was sent to family at Otahuhu, Agnes to an aunt in Manurewa. She never trusted anyone, certainly no one in authority, again. She promptly ran away.

The pastor, on the other hand was merely chastised by his church. He remained free to act as a guardian to young and impressionable immigrants and, according to Sunny, has an undertaking that he can go back to his flock when things “die down”.

Sunny takes up the story: “Social Welfare explained to me what had happened and I was shocked. Every Sunday I’d gone to church and seen the girls and some weekends they come and stayed with me.”

The only sign that Sunny had that all was not well was when, a few months before, Annie had told her that the pastor gave his wife a “hiding” because of the girls.

Only Annie had known what was going on. She told the police: “When [the wife] was out shopping, [ …. ] would take Agnes into his room and lock the door. He said he was giving her music lessons but all that time I only ever heard the occasional note come from the piano … Regarding [the wife] her and Agnes never got on and she used to hit Agnes. This was because she was jealous of Agnes and her husband spending so much time together.”

Annie’s statement continued: “Everyone used to say [ …. ] and Agnes were having a sexual affair; then there were the two letters Agnes wrote, the one at school and the other one I saw. It said this guy had her in a room with a locked door and that he lay on the floor in his underwear and he told her to lie on top and then he stuck his penis in her and her vagina got bigger and he was very happy about that… “

Obviously, neither Agnes nor Annie understood what was going on, and Agnes especially was distraught about leaving. Probably she really was in love.

“They hate me because they think I was the one who forced them home,” Sunny explains. “And then Agnes ran away. She was gone for three months. The police couldn’t find her; they said they couldn’t do anything. When I told them where I thought she was, they told me, ‘No, we’ve been around, she’s not there.’ I told them, ‘She’s been around, she’s been ringing up [ …. ‘s] place.’ But they still couldn’t find her …. “

The police, for their part, reckon that trying to find Agnes was like chasing a shadow.

When Agnes was finally delivered home in October 1991 by the pastor’s nephew, she climbed straight out her window and took off again. Her mother was frantic: “I rang the police that same night and they say they can’t do anything. I told them she said she was going to kill herself. They said, ‘Ring up the Social Welfare,’ and I said, ‘It’s night-time. There’s no one there’. Next morning I rang to Social Welfare and the lady handling that case was very busy -very busy and out of her office. I had to go next door to ring and in the end I never got hold of her.”

Agnes was only gone for two weeks before she returned this time telling her mother she was sorry and wanted to come home. But still she regularly climbed out of her bedroom window at 10 every night and stayed out until 1am or 2am.

“She kept doing this every night it’s every night and I have a really hard time,” sobs Sunny. “I don’t know what to do. I cry out. I go out in the street and look. I don’t know how to stop her. I ring up to the police, no help. I ring up Social Welfare, too busy.”

“She told Annie she had a boyfriend who had a new car to pick her up at night, and Annie said she’s sure it’s [ …. ] because that was the time he got a new car, but no one will help me.”

Then when Sunny went back to her church after the pastor had been suspended, she found out for sure where Agnes had been when she was missing: “His nephew’s wife told me that [ …. ] brought Agnes to their place and told them to leave her there with them and not tell anyone. Then he came around at night and picked her up in his car and took her for rides.”

Sunny also realised where her daughter had been the second time she ran away: “That night they brought her back and she ran away again, [ …. ] took her to another place. I had rung Mount Roskill Social Welfare, I even went round to see them … the police say they’d been round and seen him, but nothing happened.”

Within three months her daughter was dead.

The mystery surrounding the death of Agnes Ali’iva’a doesn’t seem to worry the Avondale police over-much. As both Detective Inspector Crawford and Detective Sergeant Flanagan point out, because the coroner found she died from accidental drowning, they have fulfilled their duty under the law. Says Crawford “we rely on the pathologist’s report – the result of the post-mortem. We were unable to establish why she was in that park, what she was doing. She was still basically a runaway. There’s no doubt she was probably running when she went into that ditch … as the coroner said, there are still unanswered questions. But what more can we do? She was obviously a little bit unusual for a normal 12-year-old. We know she was very well developed. Koelmeyer [the pathologist] said she’d been sexually active for a long time”.

John Flanagan agrees: “We did everything possible to try and trace her movements. There were just two and a half hours, from the last sighting to the presumed time of death, that we couldn’t account for. No offence has been committed. We were trying to establish the cause of death, and it was death by drowning. We are satisfied that no other person contributed to the cause of her death.”

Mate Frankovich, the coroner on duty when Agnes died, confirms the police view: “It’s a pity, but we’ve come to a bit of a dead end. Once the file comes to me I can only assume they’ve [ the police] really hammered it, and if they had any idea of who it was they’d be putting a finger on him — or her.

“My own feeling is that this girl was running. She ran away from home fully and properly clad, then we find her with her jeans inside out and a bruise on top of her forehead. I don’t think she was struck before she went in. The poor little girl ingests water and that was it … there was no evidence of sexual violation or any invasion sexually.

“Her clothes? No, they’ve never been found. The police have been over the area thoroughly, they may be in someone’s house”.

No one mentions the sports bra Andrew Webb found knotted up by the lavatory block in Keith Hay Park. Only Mike Crawford recalls the bra and he is adamant that, although that it sounds like the one her mother said she was wearing when she went out, it had nothing to do with Agnes: “Yes, there were some items of clothing found but they weren’t Agnes’s. During the investigation we checked with members of the family the bra certainly wasn’t hers. Usually that’s all documented.”

But Flanagan, the hands-on cop on the case didn’t know a bra had been found: “If it had been hers we’d have sure known by the size.” And Sunny says they never showed her a bra… never checked any items of clothing whatsoever with her.

Why didn’t Mike Crawford inform Flanagan that Agnes had “disclosed” that the pastor had allegedly been having sex with her?

“The police were never told, to my knowledge, that Agnes had disclosed … ,” Flanagan says. “The letter wasn’t enough for us to go on criminally-put it this way, there was nothing of any evidence on it.”

Then there’s the Department of Social Welfare. The DSW, which had been heavily involved with the family for over a year during which time it had been shuffled between five different social workers, refused to discuss the case or release Agnes’s file to Metro, even though her mother gave permission. Why?

According to DSW, they are trying to protect the innocent rather than cover their own tails. Says Richard Deyell, regional manager of children and young person’s services: “I’ve taken some advice on the matter and the file contains information not just about the young woman. We’re just as bound to keep that information confidential. Your request to interview the social workers concerned is also denied.”

Detective Greg Farrant of the police sexual abuse team would only say: “The girl’s privacy is hers, whether she’s dead or alive.”

Metro: “People who commit sexual abuse don’t deserve privacy.”

Farrant: “You want a trial by media rather than by the police?” [sic]

This rush to cover up could be seen as an attempt to hide the fact that no one moved to charge the pastor with sexual abuse or violation of a minor back in August 1991 when Agnes disclosed what was happening to her to DSW when she was still at Balmoral Intermediate. Maybe the authorities were indeed waiting for an “evidential” interview and Agnes hadn’t built up a good enough relationship with any of her constantly changing social workers to talk again. Whatever happened, they blew it.

Although it was never challenged, the pastor’s statement to Constable “Bliss” Esera, a Samoan, after a three-hour interview on February 19, paints a very different picture to those of Agnes, Annie, Sunny, the Department of Social Welfare and the teachers at Balmoral Intermediate. It reads in part:

“When they initially moved in here there were no hassles with them. My wife and I took the girls to Mount Roskill Primary School. Around July last year, when the girls were attending Balmoral Intermediate, a letter was found in Agnes’s desk. This letter was apparent taken to the headmaster. I was in Australia at the time. My wife rang me and I returned the next day. “When I came back the girls had been returned to their mother. The letter which the police have, was apparently addressed me. It was some type of love letter written to me by Agnes.

“The Social Welfare apparently got hold of the letter and showed its contents to the girls’ family. I would say that the family then assumed that there was some sort of relationship between me and Agnes. It got to the stage where someone wrote to our head minister in Australia, telling of my unusual behaviour with some young girl [Agnes]. As a result I volunteered to stand down from my designation as minister. I told the head of our church that it was best if I stopped preaching until this problem had been sorted out.

“You asked whether there had been any sexual liaison between me and Agnes. I can tell you that that has never been the case. As to why Agnes wrote that love letter addressed to me, my wife and I did ask her. She said she had some feelings for me. I never viewed the girls in that light. As far as I was concerned I treated the girls like my very own children. I do admit that I spoiled them. You told me that Agnes had sexual experience. I can only assume that these sexual encounters had been with other kids at school. I have been blamed on a previous occasion for having a relationship for a woman living with us at one time. These allegations had no foundation.

“Referring to that Thursday night, 13th of February 1992. You asked me if Agnes turned up at my place that night. Agnes did not come to my place. She would have stayed there. I was aware that she was staying away from school again. I would have taken her home…

“They all assumed that I had done something wrong to Agnes. I would say that the Social Welfare have misled everybody. They have tried to make out that I was some sort of a monster … I was aware that Social Welfare painted a very unfavourable picture of me to the girls, calling me all sorts of names. I would also say that the girls were made confident by the Social Welfare. I actually spoke to my lawyer about the allegations made against me, both by the girls’ family also by Social Welfare. My lawyer, who’s also a church-man (European), told me to forgive them.”

When I asked Mike Crawford why they didn’t challenge this statement, he shrugged his shoulders: “There wasn’t a lot we could do … usually in a case involving sex you’re relying on scientific evidence as well, you’ve got to have corroborative evidence. We can’t really act on the evidence of a dead person. Yes, we were aware what Agnes had disclosed but this didn’t come to light until she was dead.”

Exactly what happened to Agnes Ali’iva’a on that murky night is likely to remain a mystery. But that doesn’t make it all right. Who was with her? Who ripped off her top so roughly the skin on her shoulders was broken and bruised? Who frightened her so much that she pulled on her tracksuit pants inside out before taking off, half naked, hair streaming, to run headlong into the ditch like a bolting young horse?

It is almost certain Agnes died running away from someone who was trying to hurt her. Yet no one seems to have be particularly interested in finding out who. It is almost as if, fooled by their error over the age of her well-formed breasts and sexually experienced body, the police decided from the outset that she was promiscuous and wrote her off. Even when she turned out to be just 12 years old, they seemed to focus on the fact that she was a Samoan runaway from a bottom-of-the-barrel family.

And it’s difficult to escape the impression that because Agnes wasn’t actually murdered, the overstretched police didn’t try very hard to find out how she ended up dead in the drain. Contrast their actions with the uproar when the skeleton of Leah Stephens, a Queen Street stripper/prostitute who disappeared three years before was found in the forest near Muriwai. Even before they established that Stephens had been murdered, a 30 strong team of police cleared 22,000 square metres of forest floor looking for clues. Another specialist squad grid-searched 25 square metres around where the skeleton had been found. Why didn’t the police try that hard to find out what happened to Agnes?

Even though we don’t know exactly what happened, it is safe to say that in the broadest sense, Agnes Ali’iva’a died from neglect and betrayal. She was let down by her adopted country, her family and community, the police, the DSW, the hormones that gave her a woman’s body with a child’s trust and most of all by the person she should most have been able to trust.

“What would have happened if she’d been a flat-chested, blonde and blue-eyed 12 year old? There would have been a whole different emotional loading on the case. And there would have been national outrage. The papers would have picked up the story, Holmes would have been in a frenzy, as would talkback radio, to say nothing of John Banks. Probably someone would have started an appeal to send her twin to Disneyland.

But as it was, nothing happened. The police and the welfare authorities closed their files.

The Auckland City Council didn’t even fence the ditch.

–