Jul 14, 2025 Society

I’ve been thinking lately about free speech. As a journalist who feels troubled by the sudden rightward lurch toward illiberalism by Western governments, I’ve been increasingly keen to write about free expression and the importance of defending it. For some reason, though, I believed I wouldn’t need to worry about sounding like a complete moron — that I’d just ‘read enough’ and suddenly find myself able to synthesise information into an articulate, watertight, convincing argument in favour of my current position on what is perhaps one of history’s most vexing political and philosophical questions.

This was overconfident of me in a few ways, the most salient being that, despite doing a fair bit of reading, I can’t seem to land squarely anywhere on the issue. I tend to agree with New York magazine critic Andrea Long Chu, who wrote in a 2021 book review that she was “generally in favor of the artistic freedom to provoke and offend, except when I am not. I am generally opposed to the censorship of troubling or controversial speech, except for when I am not. How do I quarter that orange? Well, I exercise judgment, or at least I try to.”

On the face of it, this seems like a not-particularly-satisfying answer, like Chu’s trying to have things both ways or sit in the middle when she needs to take a side. But I find that there’s something about this halfway position that feels more honest than confident certainty. I think what Chu is acknowledging, in her typically arch style, is that hardly anyone has a consistent framework, when it comes down to it, about what should be allowed to be expressed in the public sphere and what they think is beyond the pale — what should be censored. That really, we’re all trying to have things both ways when it comes to freedom of speech, because what we think it’s okay to say and what’s beyond the pale is so deeply emotional. In reality, much of the speech and expression that we feel is worth defending, or that we believe needs censoring, is dictated not by reason but by a deep gut reaction that helps us to distinguish right from wrong. This gut feeling is totally subjective, different not only between different people, but within the same person in different contexts and times of their life.

For those on the left of the political divide, which is where I locate myself, there has been a tendency to dismiss the importance of free speech on the grounds that it’s a right-wing-coded grievance issue used to defend the spread of ideas any good leftist would find abhorrent. This has been the case for most of my adulthood. I was born the year the Berlin Wall fell, and I think it’s relevant that people in my cohort and those slightly older didn’t meaningfully experience the Cold War era, and that we came of age during a period of liberal cultural ascendancy, when the majority of free speech issues discussed widely in public revolved around people wanting the right to say or act against the grain of progressive social change, without pushback or consequences. The now-common position for most of those on the left is that any defence of those speakers’ right to do so is de facto as morally odious as the content of the speech itself.

From that position of moral obviousness, behaviour that suppresses frowned-upon speech is often justified as righteous action. This is usually where I get stuck with my own internal reasoning. Is shutting down an event featuring a speaker with extremely far-right views, either by direct protest action or through social pressure to have the event cancelled, an act of illiberal censorship, or is it necessary to protect a tolerant society against the intolerant, as Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper argued when he conceived his “paradox of tolerance”? Is it simply winning, which is what political actors are meant to try to do? How repugnant would the speaker’s views need to be for suppression to be justified, and who gets to make the call? How exactly do we quantify potential harms, and how are we supposed to balance them against encroaching state interference in our freedoms, not to mention the chilling effects of self-censorship in the social media age? Does being worried about the answers to these questions mean that I’m treating the issue with the seriousness it deserves or that I’m just a moral coward or worse — a centrist? Do I even care about being a centrist any more?

The American writer Freddie deBoer wrote in a 2022 newsletter that some of the most irritating posturing about freedom of speech online comes from leftists who are “absolutely certain about everything. They don’t believe there are any hard political questions. They don’t think there are any tensions or contradictions in their ideology.”

While deBoer, a left-wing writer, was making an intra-group criticism, the same accusation of disingenuous moralising could be made of the right. My current position, that freedom of speech is a hard political question that I spent too long dismissing as a mere cudgel of annoying dipshits like the Free Speech Union, has been clarified in the last year and half: since Israel’s defence minister announced that in response to the attacks of October 7, his country would be “fighting against human animals … and acting accordingly” in Gaza; during the months and years we have watched through our phone screens civilians getting bombed, or slowly starved, or shot in the head by snipers; and in how long it took for people in the public sphere to call something that was quite obviously a genocide a genocide. It was a crazy-making time, and I still can’t believe how bad things had to get before it became widely acceptable to state the incredibly obvious without inordinate amounts of hedging and pushback.

Palestine has always been the right’s Achilles’ heel in modern free speech debates — it has been, for decades, the one political issue you are actually not able to talk about publicly in the West without risking your reputation and livelihood, and now your actual freedom. But it’s never been a cause championed by the usual free speech proponents. In November 2023, I remember waiting for the Free Speech Union to chime in when Chlöe Swarbrick was raked over the coals for using the slogan “from the river to the sea”. They were nowhere to be found — until a few weeks later, when they popped up defending a counter-protester at a pro-Palestine rally who had her sign torn up by the police.

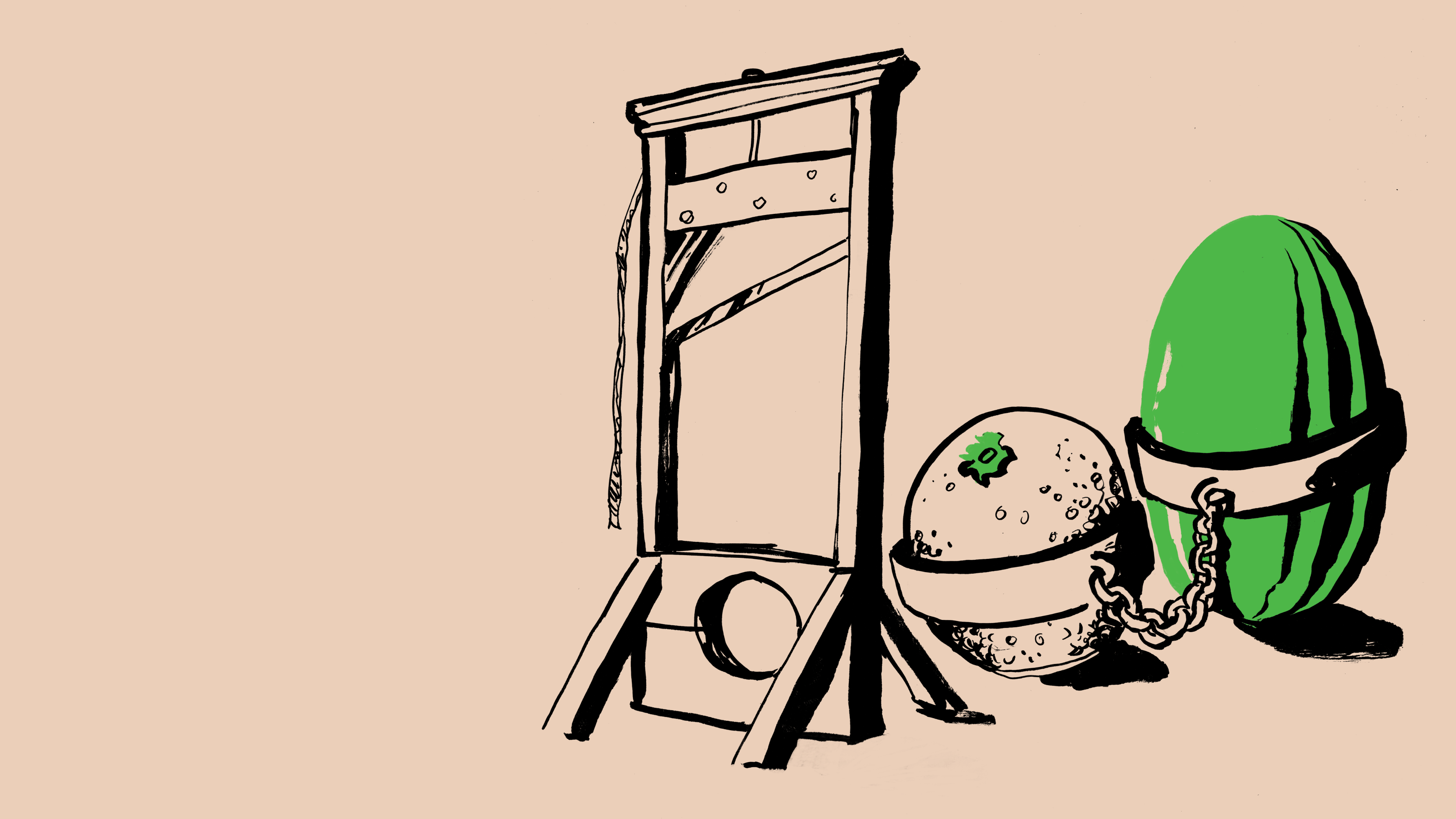

The most worrying news is currently coming from the States, where pro-Palestine activists have started to be arrested and detained on extremely flimsy charges. I remember reading about the first arrest, of Columbia University student and green-card-holder Mahmoud Khalil in March, and feeling a chill of realisation. This is why we shouldn’t surrender the righteous principle of free speech to be selectively applied by annoying dipshits, why we can’t act as if there are no hard political questions. I’d rather sound like a moron or a wishy-washy centrist while trying to exercise my judgement than glibly allow our right to say what we think to be taken away.