Feb 13, 2020 Politics

Why our beaches are swimming in shit, and what the council is doing to fix it.

In the evening, the Newmarket Stream smells like shit. Not the whole length of it, but if you wander through the gully down by Newmarket Park and trace the winding track to the overflow point at what is appropriately known as Hells Gate, there are moments when the scent on the breeze is unmistakably that of human shit. And, unfortunately for Stephen Morse, his Remuera home is often directly upwind.

The smell is the worst on a weekday morning, when everyone is shitting and showering in unison before heading off to work. The second-worst time is when he arrives home, just before dinner. “It makes me sick to my stomach,” he says. Morse is worried it’s caused his home, which he bought in 1999, to lose value. He wants a halt on any new developments in the area until the situation is brought under control. (When it’s suggested this might be difficult due to Auckland’s housing crisis, he disputes such a thing exists.)

Walking along the banks of the stream, Morse points to bits of crepey rubbish wound like papier mâché around low-hanging branches above the water and once again expresses disgust. It’s toilet paper, he claims — proof the sewer pipes overflow too often and too high. It’s hard to tell from the track whether it really is toilet paper, but there’s no denying it looks bad.

Like much of central Auckland, Newmarket has a partially combined stormwater and wastewater (sewage) network, so there are huge swathes of the city where the pipes built to take the water from our toilets and showers are the same ones that rainwater flows into. The pipes are supposed to carry their load south to the Mangere Wastewater Treatment Plant, but when it rains, many of them overflow (as they’re designed to do) to designated spill points, and all that churned-up, shitty water is discharged into our creeks and streams, onto our beaches, and into our two harbours.

This happened on Christmas Day 2018. Just before lunchtime, what had been a drizzly morning finally started to clear. Torrential rain had caused flooding around the North Island the day before; 63mm of rain had fallen at Auckland Airport, the wettest Christmas Eve on record. Some people spent Christmas morning without power.

The optimistic families around Auckland who decided to risk moving Christmas lunch outside quickly regretted the decision as drizzle gave way to thunderstorms. That’s when everything went to shit. The council’s colour-coded warning system responded. “I got a whole lot of media calls, ‘Why is everything black and red?’” Auckland Council Safeswim programme manager Nick Vigar recalls.

Vigar is tasked with facing up to media every time something goes wrong with the city’s stormwater network — like when millions of tonnes of water used to fight the International Convention Centre fire at SkyCity ended up in Viaduct Harbour. Frank and good natured, the only time during our interview when it feels like he is trying to control the narrative is when someone mentions an animation the council created last summer to track sewage flow around Auckland’s harbours. “Don’t call it the poo tracker,” he sighs.

During that stormy Christmas break, a dozen beaches around Auckland were put on black or red alert by Safeswim, a joint initiative by Auckland Council, Watercare, Surf Lifesaving Northern Region and the Auckland Regional Public Health Service, which predicts how suitable a beach is for swimming. If you look on Safeswim’s website and see a little green circle with a water drop and a tick, that beach poses low risk of sickness. Any beach with rates of enterococci bacteria below 280 per 100ml of water will be green. A red circle with a cross means high risk of illness from swimming — above 280 enterococci per 100ml of water. A red swimmer with a cross means a long-term no-swim alert, and a black circle with a cross means an actual and reported sewage overflow.

We’re a city of water lovers; according to a recent council survey, more than two-thirds of us rate clean waterways and beaches as our most important “must-have” — a significantly higher proportion than those who thought having somewhere to spend quality time with family was a “must-have” (make of that what you will). But any time there’s a decent downpour in Auckland, Safeswim’s interactive map starts to turn from green to red, especially at the isthmus beaches to the west of the Harbour Bridge. It’s a familiar scene: all these beaches and nowhere to swim. In late January last year — the height of summer — 48 beaches were flagged red or black in one week. So why are so many of our beaches no-go zones so often?

First of all, Auckland has an unusually high number of beaches for a city of its size, meaning the chance of any one of them being contaminated by dirty water at any given point is high. Then there’s our frequently wet weather, which compounds the final and underlying cause of a lot of our beach’s problems: the central city’s woefully overloaded and outdated combined water network.

The Safeswim team charts beaches on a table, ranked from cleanest (like Devonport Beach, which is swimmable more or less all year round) to dirtiest (like Coxs Bay, one of eight sites with long-term warnings in place). Vigar points to the lower half of the table. Many of the bays down the bottom are in the affluent, inner-western part of Auckland: St Marys Bay, Herne Bay, Home Bay. “Combined, combined, combined,” he says pointedly. From November 2018 to April last year, Home Bay was marked red or black, on average, one day out of every three. Herne Bay was one out of every four.

Like so many infrastructure projects, when the combined water network was built in the early 1900s, no one could have predicted the way the city would change and grow. At the time, Auckland’s population was a fraction of what it is now. Later, as plot sizes shrank to accommodate modern medium- and high-density housing, the pipes stayed the same while the amount of water and sewage sent through them increased exponentially. As more land was built on or paved over, the ground’s ability to soak up rainfall shrank, sending water running off roofs and roads and into the combined network instead. Meanwhile, more and more toilets, showers, washing machines and everything else responsible for creating dirty water (by the 1960s being sent through the pipes to Mangere for processing) were being plumbed in.

Today, about 16,000 homes, mainly in inner-western suburbs, still use the old combined system. Whenever Auckland has a “very wet day” (which MetService defines as 5mm of rain or more), the pipes are overwhelmed and spill, as they’re designed to do. As many as 100 times a year, stormwater mixed with wastewater (which includes not just the human excrement you’d expect, but also everything we flush down the toilet, like tampons and dental floss) overflows along with stormwater into streams and onto beaches.

Vigar describes the situation we’re in now as “death by a thousand cuts”. “There is no point at which you could say it suddenly got worse. A couple of spills a year became a half a dozen, in the next decade became 20, and then the next decade became 30,” he says. “Fundamentally, if the question is, ‘How did we get to this point?’, it’s that Auckland just grew past the capacity of its infrastructure.”

The reason things have been allowed to drift along aimlessly like this is the same reason anything ever drifts along aimlessly: lack of money and a historical lack of will to spend what’s there. “Legacy councils didn’t bite the bullet on something they knew needed to happen,” Mayor Phil Goff says.

The fact Auckland is built on swathes of volcanic rock has exacerbated the issue: basalt formed by lava flows is particularly tough, making it tricky and expensive to lay pipes through.

But every problem has its tipping point. In the early 2000s, Watercare’s plan to build an enormous $1.2 billion Central Interceptor (CI) sewage pipeline was put into motion and last year, the project finally broke ground. Early this year, the first part of the 4.5m-wide, 13km-long tunnel will be dug 110m below ground, using a 150m-long German-designed tunnel-boring machine. When it’s completed, the CI will run from Grey Lynn to Mangere and reduce overflows on the western beaches in central Auckland and waterways by more than 80%. The designated spill spots will reduce from 219 to 10, and each is predicted to overflow fewer than 10 times a year.

Goff wants the project done yesterday — he says the fact the CI’s on track to be completed by 2025 is because he made the call as mayor to bring expenditure forward so it could be finished faster. “You can’t be a world-class city and every time it rains have the stormwater flow into the wastewater and wastewater overflow onto the beaches — that’s 19th century, not 21st century.”

Under Goff, the council has also introduced a water-quality targeted rate, which is projected to raise $452 million in revenue each year for 10 years to fund efforts to clean up Auckland’s beaches and waterways, the largest being what the council calls the western isthmus water quality improvement programme. The project will see some properties in the inner-western suburbs have their wastewater separated from the combined network, an enormously expensive and disruptive operation that involves digging up private land and costs an estimated $60,000 per property. Other homes will simply get “plugged in” to the CI, which is less expensive, but not an option for every household, because the treated freshwater discharged into the Manukau Harbour, which has a saltwater ecosystem, can’t exceed consent limits. You don’t want to fix one side of the city’s water issues only to create new problems across town.

The Central Interceptor is unfathomably huge. The much-touted height comparison (it’s as tall as a giraffe!) is impressive, but so is its snaking length — nearly four times as long as the City Rail Link. The pipe will head underneath the Manukau Harbour at Hillsborough Bay, across the Mangere inlet, under Ambury Park and poke its head back up at the treatment plant by the inner edge of the harbour. In charge of the project is Shayne Cunis, a tall and genial bloke who is confident, like all people allowed to talk to journalists in the middle of a major project are, that everything is going to plan. “The problem with large projects is they go badly — we’re not going to,” he says.

The CI’s scale is internationally significant and there’s a problem-solver’s joy in figuring out how to circumvent the challenges this particular project faces. “This thing is designed to last 100 years,” Cunis says. I picture him slapping the side of the CI tunnel like a car salesman promising great mileage out of a second-hand Toyota. It will also allow Auckland to keep growing. It will run mostly in a direct line from north to south and create a more efficient route than the clockwise journey wastewater from the west currently makes around the city before ending up in Mangere.

Cunis runs a team out of Eden Park, chosen in part because it’s near one of the project’s first active construction sites, in May Rd, Mt Roskill. It’s also a nice moneymaker for the stadium, which was bailed out to the tune of $63 million early last year, after failing to pay back a council-guaranteed bank loan. That’s exactly the kind of fiscal disaster Cunis is adamant won’t happen with the CI. He assures me that after contractors were procured, the project was still coming in under budget. There’s five and a half years left, though, I helpfully point out. Surely that’s plenty of time to blow the budget? “Yeah, thanks for that,” he says. “That’s on the KPI [key performance indicator] of things we’re trying not to do — but you’re right, most of these big projects… have problems.” Then he’s back on message. “Everyone here is committed to delivering this on time and on budget.” An absence of problems is the CI’s ultimate goal — the mark of success will be everyone eventually forgetting it’s there. As Cunis says, “No one wants shit on their beaches.”

The bright-orange drone recedes to a speck, disappearing into Rangitoto as it buzzes away from us across the still water at Kohimarama Beach at roughly the same speed as a grizzly bear running at full pelt. The sky is clear and bright, but the sand still dense from yesterday’s rain. Contractors from engineering and environmental consulting firm PDP are collecting water samples here on Auckland Council’s behalf and the conditions need to be just right: a decent amount of rain, followed by a still day like today.

Previously, the result from a single water sample during the week would dictate Safeswim’s official water-quality rating for several days and often into the weekend. A University of Auckland microbiologist involved in recent changes at Safeswim was quoted in the New Zealand Herald in 2018 as saying the accuracy of that approach was “about random”.

The programme now relies on long-term data modelling to predict water quality at Auckland’s beaches, based on recent rainfall. Water-quality ratings are not based on a single recent sample, but rather on the predicted likelihood of an overflow based on data collated from numerous previous samples taken following wet weather (each site is sampled about 26 times a year). An exception is black flags, which are based on observed sewage overflows, not modelling — such as a leak from a sewage pipe detected in Browns Bay in October last year.

Nick Vigar concedes Auckland Council’s data collection has historically been “not good enough”. Some samples were taken only in summer, some were taken in wet weather, some were taken by helicopter, others were taken by hand. “We had really variable data quality. The main problem with the old weekly Safeswim sampling is that 90% of the data you collect is dry-weather data. And yet it’s wet weather when we know [the pipes overflow].” In December 2018, the way water samples were collected was made more uniform throughout the region, and Vigar is confident Safeswim’s data has improved as a result.

It might seem counter-intuitive, but it’s actually much cheaper, not to mention faster, to send a helicopter out to test a bunch of beaches one after the other than it is to send small teams out on the road to wade in and scoop out a sample by hand. But collecting samples too far offshore isn’t much use for modelling safe swimming conditions. Samples are now taken in knee-deep water at all beaches, and only at those like Kohimarama, which are regularly used for events, is the drone used to sample water further out from shore.

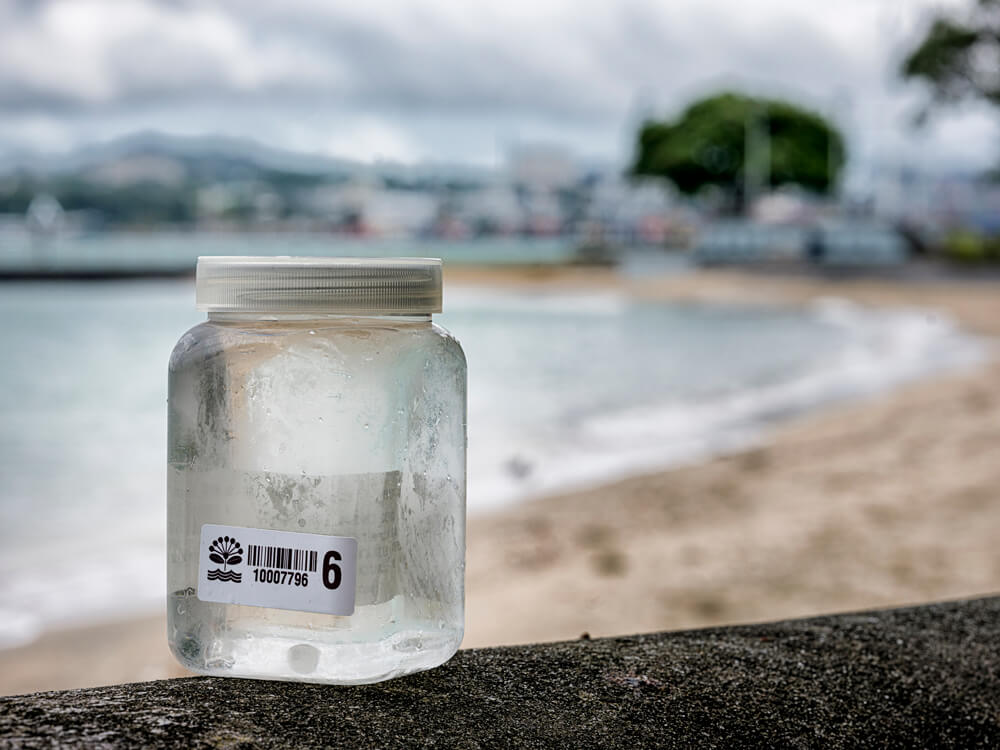

As the drone returns, a small plastic sleeve sways below, bulging with seawater. A contractor grabs it with rubber gloves on and unclips it from a long orange rope before piercing the side with a plastic straw. The water drains into a sampling pottle, which is put on ice to be taken with the day’s other samples to the lab for testing.

For more great videos, check out our Youtube Channel.

Over in Devonport, a similar process is under way, albeit with slightly fewer technical components. Workers for consultants Mott MacDonald pull on rubber waders and venture out into the choppy surf to collect samples by hand. An orange “Mighty Gripper” pole with a little claw at the end is clasped around a pottle, which is plunged into the waves and filled with water for testing.

The lab tests are looking for the presence of two bugs: E. Coli and enterococci. Both are bacteria that live in the guts of mammals, including humans, and they are reliable indicators of faecal contamination in water. Neither bug is usually likely to make you sick by itself, but the other pathogens in poo, such as giardia or campylobacter, will.

When a beach on Safeswim’s website turns red, it doesn’t exactly mean don’t swim. It means there’s an above 2% chance that, should you choose to swim, you will get sick. Safeswim doesn’t distinguish between a 2% chance and a 10% chance: both will show red, based on modelled predictions. Before Safeswim’s modelling predictions, a blanket 48-hour warning was placed on most beaches in central Auckland following heavy rain, even though lots of beaches disperse dirty water with the tide faster than that. The imprecise nature of the warning led many to disregard it. Vigar hopes the more responsive Safeswim website will encourage people to really consider when they’re being given a warning, and make an informed choice.

This raises the question of how many times something we didn’t know about didn’t hurt us. Increased awareness about what’s in the water has perhaps led to a perception water quality has suddenly become a lot worse. “I don’t think people made that connection,” Vigar says. “People were swimming, blissfully unaware.”

Initiatives like the CI and the western isthmus project will help improve water quality, but the combined network isn’t the only way sewage gets onto beaches, and it won’t get rid of red and black flags entirely. In Takapuna, where the pipe networks are separated, the beach has been under close observation by Watercare after it was found to be unswimmable for a large chunk of summer in early 2018.

Since then, Watercare has inspected hundreds of properties’ pipes to check for cross-contamination, in a quest to find the root of the problem. Pipes are fragile things — they can crack with age or if tree roots start growing through them, or can become blocked with fat or debris, and when that happens, wastewater can leak or spill where it’s not supposed to. A blocked gully trap, for example, can cause wastewater to bubble up onto people’s properties, or out into the road where it ends up in a storm drain. It’s also not uncommon for properties’ wastewater systems to be improperly plumbed into the stormwater network, or vice versa. The former causes the pipes to discharge sewage and greywater straight into the stormwater system, which flows directly to the sea; the latter overwhelms the wastewater network and contributes to wet-weather spills. The amount of stormwater that one pipe will divert into the network is the equivalent of 40 houses’ worth of wastewater.

In Takapuna, about 10% of the houses checked were found to be in some way faulty. To test where faults might be, white smoke is forced into an open manhole cover, and a team of Watercare staff crane their necks checking if they can spot it coming out at any nearby properties. During a check on a blisteringly hot day last March, an improperly connected stormwater pipe made itself known as smoke billowed out and above a house’s roof.

Watercare network efficiency manager Anin Nama says trying to achieve perfect water quality in an urban environment is a Sisyphean task. Animals poo, too, and there are plenty of dogs, cats and birds living in the city, both wild and domesticated. “You can address the human component, but you will still have this natural background contamination that you just can’t address.” You can also raise all the awareness you like, but there will still be people who plumb their washing machines directly into the stormwater system, or pour cleaning chemicals into a streetside drain. Nevertheless, they keep trying. What else can you do?

It’s popular to blame the council when anything goes wrong in Auckland, but that’s only sometimes fair. While it’s not unreasonable to ask why something wasn’t done about our beaches sooner, it’s also futile. They do appear to be dealing with the problems they’ve inherited, and the mayor seems particularly keen to make his leadership the one that sees a real turnaround in water quality. But none of the changes needed will happen overnight, so for now all we can do is wait to see how well these plans pan out.

On an oppressively humid Sunday afternoon, I make plans to head from my apartment in the CBD to a nearby beach to take my first dip of the summer. I can’t wait to submerge myself under the waves. About an hour before high tide, a brief yet heavy summer storm passes over Auckland, so I check Safeswim before leaving home. All the beaches are red.

This piece originally appeared in the January-February 2020 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline ‘Unswimmable Auckland’.