Sep 11, 2014 Politics

Yes, we know. It’s meant to be all about policy, and serious debates and stuff. But when you scratch beneath the surface of political campaigning, there’s quite a lot to discover, and they don’t always want you to do that.

The symbolism of public events

The Labour Party launched its election campaign in the Viaduct Events Centre, a waterfront building created for the Rugby World Cup in 2011 and given centre stage by the America’s Cup campaign. It’s a symbol of entrepreneurial, business-oriented, we-believe-in-ourselves Auckland. That’s Labour for you, desperate to believe in themselves.

The National Party launched in the Vodafone Events Centre in Manukau, the heartland venue of south Auckland, the epicentre of both Maori and Pasifika cultures in this country. That’s National, desperate to identify with the diversity of this city — although when John Key got up to address the crowd he rather spoiled it by saying he was pleased to be in “Manner-cow”. It was lunchtime and there was a Sunday market in full swing outside the venue, but none of the National crowd went over to buy anything, or even browse.

Labour warmed up with Don McGlashan and a large crew of musicians singing “Nature” and the Split Enz classic “Time for a Change”. National had a 13-year-old kid from Manurewa High rapping and telling jokes — and boy was he good — and a South Auckland cabaret band: Tell me when will you be mine, Tell me quando quando quando… Boy were they not good. They also did the Beatles: Shake it up baby, twist and shout.

Who goes to campaign launches? Party volunteers — young and middle-aged — in campaign T-shirts, plus elderly party members and ethnic groups. Especially Indians, there in force for both parties. But while the same sorts of people go to party events on both sides of the divide, you could not in a million years confuse the two. Audiences at events like this are the purest possible expression of who the parties appeal to: National’s core supporters are comfortably wealthy or at least doing their best to look like they are; Labour’s are demonstrably not wealthy, or doing their best to look as if they don’t care about money.

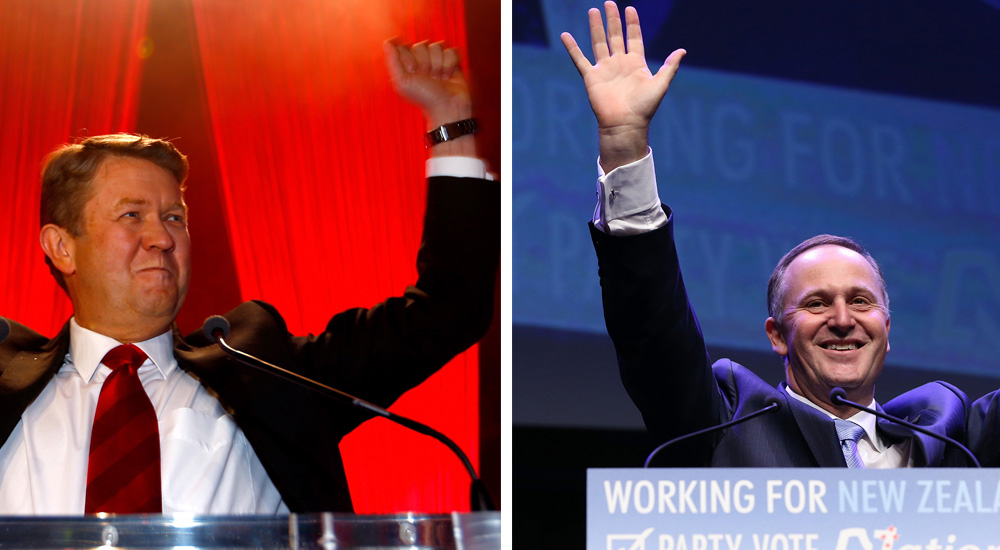

Labour presented a show produced by events supremo Mike Mizrahi. It was dramatic, for sure, with big screens and so much red — the lighting, the drapes — there was a moment I wondered if this was going to be the Red Wedding. A massacre on launch day, wouldn’t that be something?

National scarcely bothered. Some balloons, but not a lot, and a bit of blue lighting. National’s campaign theme tune, which you can hear on their TV and radio ads, has a definite Slim Shady feel to it, although some political journalists have also compared it to Native American dance music or possibly a Roman slave march.

National launched the day after that magnificent All Blacks slaughter of the Wallabies at Eden Park, and deputy leader Bill English warmed up the crowd with rugby jokes. Richie’s boys had put 51 points on the Aussies, he said, so the challenge for John Key was to do that too.

When Key got on stage, grin a mile wide, the first thing he said was, “Breaking news. Richie McCaw’s texted and he said, ‘Yes you can.’”

What about, next election, we treat the All Blacks like religious leaders and make them off limits for politicians?

Kiwis: progressive and conservative

With a few grand exceptions, the entire period of New Zealand’s political history has been characterised by two conflicting trends. Our historical destiny is progressive, but our instinct election by election is conservative.

On the progressive side, we’re proud of the Treaty of Waitangi, votes for women and workers’ rights in the 1890s, the creation of the welfare state in the 1930s, our nuclear-free stance in the 1980s, support for gay legal rights over the years, and so on.

Yet our conservative instincts lead us to vote centre right far more than centre left.

In practice, this gives us a repeating electoral cycle. Labour (and before them, the Liberals) introduces reforms, and then National beds them in. When we’re ready for more reforms, we vote Labour back; when National returns, they usually leave the reforms in place.

We look to Labour to define the relationship of state and citizens, but we believe National is better at managing it.

They’re not lunatics, those people on the fringe

Depending on your political persuasion, it’s easy to think of John Minto, Christine Rankin, Annette Sykes, Jamie Whyte and Colin Craig as a lunatic fringe. That’s not right. While there are, as always, some genuinely whackjob parties standing in the election, Internet Mana on the left and Act and the Conservatives on the right do not qualify.

Each in its own way represents a relatively pure expression of a coherent political world view — unlike both the leading parties, whose political philosophy is badly compromised by electoral opportunism.

Having Minto and Craig, say, in Parliament would not transform the debating chamber into a circus. It’s more likely to raise the tone, because they’ll be mounting proper arguments they believe in, about important things. We’d all benefit from a better exchange of ideas. (And no, Colin Craig will not mention chemtrails. Ever again.)

Besides, it would be a lot more fun. The first rule of politics is to entertain — to make us feel it is worthwhile listening. That’s something David Lange knew and few other politicians have ever learned.

What does it mean for Auckland?

Auckland will be greatly impacted by this election. Build the Puhoi to Wellsford highway or get started now on the City Rail Link under the central city? Whole philosophies about transport, economic development and community life are inherent in that one issue. Efficiency on the roads, the density of urban areas, the relative importance of roads for recreational as well as business use (“holiday highway” is a term of abuse in economic planning circles, but that might not be what you think).

Wherever you stand on transport spending, don’t forget this: a vote for rail is not a vote against roads. The better the commuter rail service, the easier it will be to drive on the roads. The better the rail freight service, the fewer trucks you’ll be competing with too.

One really big Auckland issue has remained under the radar: the future of the container port. Neither side has committed to a plan, even though the whole country desperately needs an integrated nationwide port and freight development strategy.

Why haven’t they? Because any such plan will involve telling some cities they are going to miss out. Could be Auckland.

Don’t worry, be happy

The National-led government has had one overarching political goal in the last six years: to build business confidence. Related to that, it has had a more general goal: to build confidence in the wider community.

Cynically, you can call this the don’t-worry-be-happy approach to politics. And it’s true that if all a government cares about is making us feel there is nothing to worry about, they might as well give up on long-term goals, principled policy development and anything more than a random strike rate for making things better.

And yet, confidence is essential. It is a powerful driver for success. When business is confident, it invests, and that creates employment, more economic activity, more wealth in the community. John Key, Steven Joyce and Bill English say this a lot, and they’re right.

The same is true more generally. If we all feel things are going well in the country, we are less likely to be scared of crime, more likely to embrace the opportunities in front of us, more likely to take risks and therefore taste more success and more happiness. Those things all make society healthier, and they create more economic activity too. Confidence is enabling.

This election, one way of phrasing the big question is this: is our confidence in the leadership of John Key and his government good for us, or is it disguising a lack of progress on strategic goals? Are we good because we think we’re good, or have we got stuck at the barbie with too many drinks inside us and rain on the way?

By the way, business confidence in the Auckland economy dropped sharply in the last survey. Chamber of Commerce head Michael Barnett said, “You could blame it on seasonal issues like winter or on the uncertainty imposed by the general election, but there are worrying indicators in play.”

What the polls tell us

Although this is our seventh MMP election, the media still mostly reports on polls as if they are two-party races. National is doing so much better than Labour. And yet, when they dig deeper, they also tell you it’s a close race.

The reason National is doing so well in the polls is that none of its potential coalition partners has any popular support at all. National hoovers up all the centre-right votes — largely because of the personal popularity of Key and partly because the public long stopped listening to anything Act or Peter Dunne says.

The reason Labour is not doing so well is fundamentally because it shares the centre-left with another strong party: the Greens. Sure, it could do better under a more appealing leader. But the dual strength of Labour and the Greens is a long-term reality in New Zealand politics.

What the polls tell John Key

As Key’s hagiographer John Roughan revealed in his recent book (read our review here), John Key has the uncanny ability to “look at two numbers” and tell you what they mean. He knew how to read trades when he worked in international finance and he knows how to read poll data now. What’s more, National polls every week.

So when Key says, “I don’t think New Zealanders care about that very much,” he’s almost certainly right, because he knows. It’s good political leadership to know what the public cares about and to focus on that. It’s also good political leadership to know what’s important anyway, and use your influence to make the public care about it.

That’s another way to look at the choice this election: how much does John Key use his popularity to do what he knows is right, even if he also knows it may not help him stay so popular? It’s called using his political capital.

Oh, those wacky Greens

Not so long ago, National’s Joyce and English took every chance they got to beat a drum about the weird and wacky policies of the Greens. The strategy was twofold and very simple. First, ignore Labour, which had the effect of making them irrelevant. Second, demonise the Greens, which was the party National wanted most of us to think is not fit for government.

But Greens leaders Russel Norman and Metiria Turei are demonstrably not crazy and their policies are not profligate. Besides, as they are unlikely to be the largest party in a coalition with Labour, they will have a lesser say on policy.

The Greens have a strategic goal: to engineer a restructuring of the New Zealand economy so that we minimise the damage that will be caused by climate change, and maximise the opportunities — in new industries, new relationships with our environment and new ways of relating to the world — that it may bring.

To achieve that goal, they need to be in power. Just like Labour and National, they are serious about the prospect of becoming part of a government. Their principal short-term goal, therefore, is to prove themselves fit to govern.

The new demon

Recently, National has started treating the Greens more like Labour: that is, they ignore them. That’s because they’ve got a better target to demonise: Internet Mana. Or to be more specific, Kim Dotcom.

National now regards Dotcom as one of their two best weapons (the other is David Cunliffe).

How did Internet Mana happen?

One way to describe Internet Mana is that it’s a reverse takeover of Kim Dotcom’s political fury — and money — by elements of the left.

Dotcom is not a leftie. He makes no secret of having been driven into politics by his intense dislike for John Key. Inasmuch as he has expressed any political views, they have tended to be libertarian or anarchist: the sort of free-market policies that enable entrepreneurs to do whatever they want.

Dotcom, in fact, resembles nothing so much as a 19th-century railroad baron in the American Midwest: a pioneer of a new technology that would utterly change the way the world worked and make its owners immensely rich — provided they were free from government restraint and ruthless in their handling of power and influence.

That’s almost the diametric opposite of the allegiances of Hone Harawira and Dotcom’s own party boss, Laila Harré. No matter. The Mana Party, cash strapped, under-organised on a nationwide basis and marginalised in most political debates, spotted an opportunity to become ruthlessly successful themselves. So they took it.

Dotcom, for his part, spotted a chance to ensure his party got into Parliament. On both sides, they knew they would make a lot of headlines — and in an election, unless people are talking about you, you’re nothing.

Was the marriage of Internet and Mana brokered — or at least helped along — by Matt McCarten? He’s a close friend of Harré, former organiser and adviser for the Mana Party, a man much versed in the dark arts of political campaigning, and currently the campaign supremo for Labour.

Talk about unintended consequences. The whole raison d’être of Internet Mana is to increase the chance of changing the government, yet the alliance has damaged the very parties who are central to that aspiration: Labour and the Greens.

It hurts the Greens, because it sucks oxygen out of their attempts to become the leading leftist voice in New Zealand politics. And it hurts both Labour and the Greens, because it sets Dotcom up as bogeyman for middle-ground voters.

National talk about Dotcom all the time now, which is a clear sign they know from their own polling and door-knocking how frightening he is for soft centrist voters.

Those dodgy deals

Not all electoral deals are dodgy, but some of them are.

National and Labour have adopted a different approach to electoral deals. National has advised its supporters to vote for Act candidate David Seymour in Epsom and United Future’s Peter Dunne in Ohariu, thereby almost certainly ensuring those two parties will be returned to Parliament — even though they both have almost zero general support.

National has also declined to stand candidates in the Maori seats, which enhances the Maori Party’s chances of holding one or two of them.

All three of those minor parties are currently formal coalition partners in the National-led government, and National expects to be able to call on the votes of their MPs again. This is different from the situation with the Conservative Party, which National has no arrangement with and which itself frankly admits has little chance of winning a seat. Unless Colin Craig’s party can gain five per cent of the overall vote, they will not be in Parliament.

Labour is contesting every seat, and officially it is trying to win them all. They have made no accommodations with the Greens or Internet Mana. Unofficially, there is some evidence Labour is not trying all that hard to win Te Tai Tokerau, although that’s a view the Labour candidate, Kelvin Davis, explicitly rejects. He really wants to beat Hone Harawira and win that seat.

What if the election looks really close? Will Labour actually tell its supporters to vote for Hone Harawira, thus ensuring the few percent of votes that go to Internet Mana are not wasted? Will National announce it doesn’t really mind if Murray McCully misses out in East Coast Bays? Both are possible, and both would be extremely cynical.

When the election is over, the new government must end this rort by abolishing the coat-tail provisions of MMP.

What the Maori Party will do

The Maori Party is not committed to National. It is committed to being “at the table”. It wants, most of all, to be in government or at least to have the ear of government. That means it could join a Labour-led coalition.

What’s the point of Act?

Act is a party of individual responsibility that doesn’t believe in self-reliance. If it did, it would not accept National’s support in Epsom. Act believes in freedom of choice, but not at the cost of property values in the Grammar Zone.

Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing wrong with defending property values. But you might at least have the humility to accept you have to climb off your philosophical high horse to do it.

Why does a party that claims to be enlightened and forward thinking so consistently cast itself as part of the fearful, ignorant and gloomy past? Scaremongering on crime, although we have never lived in a time of less crime. Complaining about Maori privileges even while acknowledging that Maori are at the bottom of so many of the indices of social wellbeing… It’s time we moved on.

Can Labour form a decent cabinet?

Of course. All parties look disorganised and desperate when they’re doing badly in the polls. But just as doing badly makes you look bad, doing well makes you look good. If Labour leads the next government, it will have experience (especially Annette King, Phil Goff, David Parker) and some talented newcomers to the Cabinet table (think Grant Robertson, Jacinda Ardern and David Shearer).

Labour has also taken considerable pains to cost its policies, and to make it clear they will not spend money we do not have. Yes, they will continue to borrow — just like National, which has taken the net government debt from $10 billion to $60 billion over the last six years.

Is National tired?

Not at all. John Key has done extremely well to insist on the retirement of middling talent, and the party has a raft of impressive up-and-comers at every level. The likes of Amy Adams, Simon Bridges and Nikki Kaye will step into more senior roles in a new National-led Cabinet, and work hard to succeed.

Which side is less stable?

National likes to say the choice is between stable government led by John Key, and a rag-tag collection of small parties that probably won’t be able to work together. In fact, there’s no evidence either side will be inherently more stable in power.

Power brings stability. If David Cunliffe can lead Labour to a position where they form the next government, he will have a loyal caucus.

If, conversely, John Key wins and then resigns sometime during the term, as is expected, National could go to war with itself. The revelations in Nicky Hager’s book point to some very deep rifts in the party, disguised only by Key’s personal popularity.

As for the rag-tag small parties, National currently relies on three of them (Maori, Act and United Future), and after September 20 could want to call on two more as well (Conservative and NZ First). Labour would govern with the Greens, and might have support from up to three more (Internet Mana, Maori and NZ First).

Who will the next leaders be?

Paula Bennett for National, and Grant Robertson for Labour. Both excellent debaters and very good at presenting a position. Both liked in their own caucus, much tougher than you might think, and with the sense about them that they have something to prove. That makes them hungry. And both, importantly, are possessed of enormous charm. If you don’t think Bennett is charming, you don’t understand New Zealand politics.

Is Winston important?

Yes he is. New Zealand First will probably get to five per cent, which could well give Winston Peters the power to choose the next government.

But think of it this way. He wasn’t in Parliament after 2008 and he returned in 2011 only because he benefited from the revelations in the “teapot tape” that year, when we learned John Key and John Banks had joked about elderly New Zealand First supporters.

Two lessons there. One, Peters’ core support is not really very strong. He could fade as the heat goes on. Two, little things can change everything. Will there be a few more “little things” that do that before September 20?

Oh yes.

Published in Metro, September 2014. Photos by Simon Young.

More Election 2014 on metromag.co.nz: Simon Wilson writes on the rot inside the National Party, makes a spirited defence of journalism in the wake of Dirty Politics, and spends a day on Waiheke with Winston Peters. Matthew Hooton on why National deserve to lose after the Dirty Politics revelations. And Steve Braunias shares his inimitable take on politics in his daily Campaign Diary.