Oct 9, 2017 Crime

From the Metro archives.

In 2012 Donna Chisholm looked at the rate of fatalities in police pursuits, finding more than three times as many people die in police chases in New Zealand than in Australian states of comparable size. She investigated whether it was time to ban them.

She had already rejected the idea by the time she felt the car begin to slide sideways. When she saw the lamppost looming ahead of her, she closed her eyes and prepared to die.

The 1am smash in Hobsonville killed 19-year-old driver Sina Naraghizadeh, and left Gregory-Hawke– who came to hanging upside down in the overturned wreck – in hospital for six weeks with a shattered pelvis, three broken ribs and a broken collar bone.

At 16, she has left Selwyn College and is having weekly counselling. “I blamed everyone in the car, including myself,” she says.

The crash made front-page news that Sunday morning last September but most of us soon forgot about it. There wasn’t too much sympathy for a bunch of teenagers in a stolen car driven by some kid with a foreign name who’d been drinking and smoking cannabis – particularly when the country was in the throes of the Rugby World Cup.

And yet the case – believed to be only the second pursuit death to go to the Coroner’s Court – could force a rethink on chase policy, with the family engaging lawyers to question police protocols around pursuits.

Metro investigations have uncovered unflattering comparisons between New Zealand’s record of pursuit crashes, deaths and injuries and Australia’s, where two states have already moved to ban pursuits for traffic offences and stolen cars.

Consider this:

- New Zealand police chase between 2000 and 2500 vehicles every year – three times as many as in Victoria, which has a population of a million more, and seven times as many as Queensland, with a roughly similar population.

- In Queensland, 11 people died in pursuits in the decade to 2010. In New Zealand in just five years, from 2007-2011, 33 people died. And yet Queensland moved this year to all but ban pursuits because of the unacceptable risk to public safety.

- Even before its new policy came in, Queensland abandoned around 73 per cent of chases compared to New Zealand’s 48 per cent.

- Tasmania, which banned pursuits in 1999, says it has not resulted in any increase in road or other crimes, despite claims that “anarchy” would ensue.

With another crash in Gisborne in July claiming three more young lives after an abandoned pursuit, lawyer Deborah Manning, who’s advising the families of teens in the Hobsonville accident, says it’s time for another look at chase laws. “Really serious questions need to be asked about the number of young people dying for the relatively minor offence they committed at the beginning – and the relative predictability of that being the outcome.”

Police would have seen the Hobsonville car was full of young people – at one stage there were seven, including two in the boot of the stationwagon, but two got out at a shopping centre before the crash. “It’s a high-risk approach to be chasing a car when it’s packed full of kids.”

But it seems there’ll be no reassessment with Police Minister Anne Tolley at the helm. She says pursuits aren’t a problem, those that are begun are subject to rigorous risk assessment, and New Zealanders have no stomach for a ban.

“They believe and stress to me they want our police to uphold the rule of law. They want offenders brought to justice.”

The Gisborne pursuit wasn’t really a pursuit at all, she says, because it only lasted 30 seconds before being abandoned. The police said the chase went for 90 seconds and the crash happened minutes later.

“You’re making the police the bad guys,” she says. “The people who are fleeing police are the bad guys.”

It’s easy to condemn Sina Naraghizadeh for his offending and his passengers for their stupidity, but how many of us know a teenager who’s never made a dumb decision, who’s never climbed into a car with a driver they shouldn’t have trusted, who’s never pushed the boundaries with hormone-driven recklessness?

And if that kid were yours, would it be so easy to say he deserved to die for that bad call?

Tolley says if her daughter ever found herself in a car fleeing police, “I’d want her to convince the driver to stop”.

Well tell that to Te Rina Gregory-Hawke and the surviving passenger in the Gisborne crash who tried the same thing and failed.

The only time police pursuit deaths cause a real outcry here is when the victims are “innocents”.

That happened in Christchurch in 2010 – our blackest year with 18 deaths in 11 pursuits – when 73-year-old Norm Fitt and his gym partner, 67-year-old Deidre Jordan, died. Fitt’s Daihatsu Terios was hit and flipped by Phillip Bannan, 22, a drunk and disqualified driver fleeing from police.

Adult children of the pair spoke then about how they were pleased police were cleared of wrongdoing and how any blame for the crash lay squarely with Bannan.

Two years on, Steve Fitt says he still believes pursuits are worth the risk – and he thinks his dad would agree.

“Otherwise you are encouraging anarchy. The outcome was unfortunate but it’s still the right thing to do.”

His sister Marika spoke at the funeral, thanking police for trying to prevent a horrible accident. “I knew they were doing the best they could to protect the public.”

But she now admits she has doubts. “A little part of me wonders if it can be handled differently.”

She says though Bannan was speeding and driving drunk – he was twice the legal limit – he had driven an hour and a half from Akaroa without incident before the pursuit.

She now wonders “what if” Bannan hadn’t been chased at all? “No one was in danger if they’d just left him. There weren’t that many cars on the road and maybe I think he wouldn’t have panicked as much as he did. He didn’t have a licence, his car was unregistered and unwarranted. He’s going to be looking in his rear-vision mirror because he’s scared shitless.”

It’s likely pursuing police knew Bannan’s identity – they had pulled up behind him at a red light when they would have – or could have – taken his number plate, allowing them to find and arrest him later.

As it was, they abandoned chase only 30 seconds later when they saw his Ford Mondeo speeding towards a red light at the intersection of Worcester St, just one block before he hit Norm Fitt’s car.

Steve Fitt’s view, that banning pursuits would simply encourage lawlessness, is widely backed by the public and lawmakers.

“Too much emphasis is now given to criminals’ rights and not the police. By being uncooperative and not being a good citizen they are let off with more and more things.”

Bannan, who’d had two previous drink-drive convictions and was jailed for nine years for manslaughter, was simply a pisshead loser, says Steve Fitt.

Few of us would disagree with that, but what of Fitt’s view that police have no alternative but to give chase if they see a speeding or stolen car or a suspected drink-driver?

Police in Tasmania say their ban is working well – and that support extends to the once rabidly opposed Police Association.

“We were all dead against it, without doubt,” acting association president Robbie Dunn told Metro. “We couldn’t speak out publicly against it because in those days we would have got transferred to Timbuktu. I thought, this is ridiculous… we were really frustrated – we wanted to still chase.”

The association predicted anarchy, and for a while, they were taunted by carloads of hoons doing doughnuts outside the local copshops and driving off brandishing the middle finger. But, says Dunn, the early fears haven’t been realised.

“At times people get away with it, but in the end, we identify them, take warrants out and go and arrest them at home. It does take some time. I’ve changed my mind about it personally. If innocent people are going to get killed, is it worth it? Now I don’t think it is. I don’t want to see my people chasing these bloody 16-year-old halfwits who can’t really drive anyway and having to live with some decent kid or granny being killed when they’ve gone through a red light and hit them.”

Many new officers have never been involved in a pursuit “so they don’t realise the thrill of the chase… they’re not inveterate chasers like we used to be. “

Tasmanian assistant police commissioner Donna Adams says while officers could still pursue for crimes in progress such as robbery or murder, “they’re very few and far between”. “We can’t do it for speeding, drink drive or stolen vehicles. The priority of safety has been accepted and most people fairly strongly support the policy the way it is.”

She says there’s been no impact on traffic or other crime. People aren’t drink driving or nicking vehicles with impunity because they’re still getting caught. Stolen vehicle rates are dropping, drivers rarely take off from booze checkpoints and there are seldom very high excess blood alcohol readings when drivers are booked.

A Queensland police spokeswoman told us initial analysis suggests the new policy is working there too, aided by increased penalties for evading police. Greater emphasis is now on “investigative avenues” rather than dangerous pursuits. “The loss of an innocent life is simply too high a price when there are far safer alternatives.”

Tolley says those states are different to us. Asked how Tasmania was so inherently different that a ban worked there but wouldn’t in New Zealand, she said: “They’re Tasmanians. They have a different culture, different makeup, different heritage. They have a Green government.”

Australian road safety campaigner John Lambert, an advocate of pursuit bans, says states that haven’t followed Tasmania and Queensland’s lead argue that abandoning them would be “giving in to the criminals”.

But with only about one in 10,000 vehicle interceptions resulting in drivers doing a runner, “if you do away with chasing you’re talking about a very low percentage of on-road enforcement activities”.

He says pursuits are “basically the most hazardous activity you could possibly undertake on roads legally and it’s a total contradiction for police to be engaging in them when they’re supposed to be improving road safety. The fatality rate for pursuits is 3500 times higher than for normal travel.” That’s about 500 times the crash risk of someone driving with double the legal alcohol limit.

Says Lambert: “The death penalty disappeared a long time ago and you can’t be generating a situation where you’re likely to cause someone who’s committed a traffic offence in a stolen vehicle to die – or even worse, an innocent bystander.”

While the Independent Police Conduct Authority describes New Zealand’s pursuit policies as “restrictive” and in line with the international mainstream, it’s not just Australia which is moving closer to bans.

In 2007, Victoria, Canada, brought in a policy that police had to believe a driver or passenger had committed or was about to commit a serious offence involving the imminent threat of grievous bodily harm or death. Chases for traffic or property crimes were prohibited – a move expected to reduce pursuits by 90 per cent.

In Boston, police are allowed to chase where a vehicle was being driven in a way that “poses threat or harm” and Long Beach California allows pursuits only when drivers are so impaired they might cause death or serious injury, or when violent offending is involved.

The IPCA says North American research suggests that when “violent offender only” policies are introduced, pursuits and pursuit-related injuries and deaths fall dramatically – but there is no corresponding increase in crime or vehicle offending.

So why couldn’t these policies work here?

Partly because police don’t think they could and, as Tolley says, there’s no public or political appetite for it.

In a review of policy in 2010, its Road Policing Support team said there was still too little evidence to support a ban on pursuits. Despite the international experience the IPCA referred to, it said a ban wasn’t likely to improve or guarantee public safety – and the community wouldn’t support such a move anyway.

And, in direct contradiction to the evidence in the IPCA’s review, it said: “Banning pursuits has the potential to create a level of lawlessness within the community. If criminals know that police will not pursue them, or have so many restrictions placed on them it renders pursuits futile, then the job of police to uphold the law not only becomes difficult, but almost impossible.”

Which sounds exactly like a sound bite from Police Association head Greg O’Connor, who defends pursuits at every turn. He claims New Zealand has more pursuits than Australian states simply because here, offenders have “less of a fear of the consequences of an adverse encounter with police.”

Asked for evidence of that, he says it’s “personal observations”. “I sit on boards over there and I’ve discussed this very thing with them.”

O’Connor concedes he simply doesn’t know if bans would work here. But, he says, “If anyone believes that if we only pulled over people who agreed to stop and let the others go it would make the roads safer it’s a little counter-intuitive.”

Strict protocols around what police must do in a chase – including giving pursuit controllers rather than drivers overall responsibility for pursuits are designed to mitigate the risk of so-called “red misting”. This was described in a British inquiry in 2001 into pursuit deaths where officers told of a “red mist of rage and excitement” overcoming some drivers chasing a fleeing vehicle.

One of this country’s few public critics of police pursuits, road safety campaigner and Dog and Lemon Guide editor Clive Matthew-Wilson, reckons police chase because they enjoy the thrill of it.

“Part of it is because they hate seeing people get away, and that’s natural, but police work by and large is very boring and one of the few things that’s really exciting is chasing someone. And yet it’s one of the least effective ways of catching anybody.”

A former cop told Metro of his own experience with red misting. “It becomes an intensely personal battle between the chasing officer and the offender,” he says. Police are meant to talk continuously through the pursuit (to the supervising officer in the comms centre) but that never happened in my experience.”

He recalled one chase he took through a built-up area when he was doing speeds of up to 90km/h but advising comms he was doing only 50-60km/h. “We lied to keep going because no cop wants to lose an offender.”

He’s sceptical of reports of pursuits called off just before a crash, saying in some cases police had arrived at a crash scene just seconds later, raising serious doubts that the chase had indeed been abandoned.

While a supervisor in the police communications centre had ultimate control over a pursuit the officer told us staff had become increasingly “civilianised” and lacked the experience of the sworn officers previously at the helm.

“Too much decision-making is left to the person in the car,” he says. “The chain of command still requires an inspector to take over, but the fact most are over in 40-50 seconds means there are many cases where a sworn officer never gets the chance to take over.”

He wonders if the spike in pursuit deaths in 2010 was related to the switch that year from analogue to digital radio systems. Until then, the lead car in a pursuit would be routed on to a dedicated channel that was kept clear for the pursuit. “The switch to digital doesn’t seem to have gone that well. There have been black spots that last for several kilometres and the concerns of serving officers are well known.”

Deputy police commissioner Mike Bush says while the former officer was right about the timing of the switch to digital radio, he did not believe that had contributed to pursuit crashes.

Figures supplied to Metro under the Official Information Act show that while the number of pursuits has remained fairly static, crashes have declined. Injury rates have risen, but police say that’s because until 2009 only those injuries requiring hospital admission were counted, now even minor cuts and bruises are included.

Bush says our pursuit figures may be out of kilter with Australia’s partly because of different definitions of a pursuit, and the fact that policing here was “very intelligence driven”. “We will put our staff into areas where we suspect crimes are being committed. We don’t patrol areas randomly and because of that we’re obviously going to come into contact with people who may be in the act of committing offences.”

He also pointed to a different culture among New Zealand offenders who had “an unwritten rule among themselves that they don’t stop for the cops”.

That being so, it seems no possible good could come from chasing someone who’s determined not to stop, but Bush says a pursuit would be abandoned if it jeopardised public safety.

However the IPCA’s 2009 report recommended that the risk to public safety from NOT stopping an offender should be the principal determining factor in a decision to pursue.

It also recommended that the pursuit decision be based on known facts, rather than suspicion or speculation that a person who flees may have committed a more serious offence. She said in one 2007 pursuit a police driver who breached policy by continuing a chase defended himself by saying he would have been criticised “if we had pulled out and later found the driver was fleeing from a murder scene”. The fleeing driver, however, faced no other charges than those resulting from the pursuit.

About one in four vehicles pursued by police are stolen, while 51 per cent involve a driver who is driving unlicensed or while disqualified or suspended – relatively minor offences in the scheme of things compared with the risk of crash deaths and injuries.

Yet Bush’s remarks suggest New Zealand’s pursuit policy is targeted at criminals who’ve committed other offences.

“Not all people who commit (driving) offences are criminals but most criminals commit traffic offences so it’s one way of targeting criminals.”

Bush says police are always weighing the risks and the benefits of pursuits. “If someone comes up with the right answer to this we’re always happy to listen.”

Despite his vigorous defence of the police right to pursue, O’Connor sums up the dilemma for parents and police.

“If my daughter was in a car and the driver of the vehicle decided he would flee, I would want the police to stop pursuing to reduce the damage. However, I would hate to think the driver said, ‘Well, I will drive faster here because I know the cops will pull out.’”

Manning says few chases have been challenged in the Coroner’s Court because families feel an enduring sense of shame.

“They are so disenfranchised, and when we’re talking about (injured) victims, who are the people they are most involved with in the weeks and months after a crash? The police. There’s no pulling the telescope back a bit and saying maybe the police didn’t have to chase at all.”

Sina Naraghizadeh’s father Vahid, in asking the coroner to review his son’s death, is trying to do just that. His lawyers are expected to raise concerns about why automatic vehicle location data – recording the police car’s speed and movements – could not be found post-crash and whether the pursuit was indeed abandoned.

Te Rina Gregory-Hawke says Sina was panicked into fleeing – threatened by one of the three boys in the car to keep driving because that boy was breaking curfew. It was he, not Sina, who’d stolen the car.

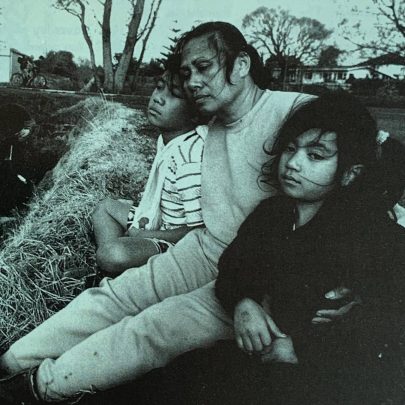

Vahid Naraghizadeh, an engineer in Iran but now a plasterer and painter in Auckland, brought his wife and Sina to New Zealand when Sina was only four. In recent years, he’d been battling to keep his son out of trouble when he fell in with the wrong crowd – and vainly asking police youth aid for help.

Though both he and his son were New Zealand citizens when Sina died, the boy was described as “an Iranian national” in reports of the crash.

“He’s grown up here in this bloody system and then they put in the paper that it’s an Iranian boy with a stolen car who died in a car crash and as soon as people read that, who cares?”

This is published in the September 2012 issue of Metro.