Jul 5, 2016 Crime

Before Terry Clark flooded 1970s New Zealand with heroin and viciously took control of the Mr Asia drug syndicate, he was just another small-time crim with big dreams.

This article was first published in the May 2016 Metro.

A hush fell in the foyer of the Civic as the crowd parted to reveal a pitched battle in miniature. Presided over by the theatre’s faux elephants and smiling Buddhas, a short, wiry 30-something spiv was throwing punches at an equally small opponent, who didn’t look much older than 15.

Watching with three mates, I felt sorry for the younger man. Chubby and bespectacled, he looked on the verge of tears as the spiv, in a grey suit with knife-edge creases and winklepicker shoes, forced him off balance and he reeled backwards towards us.

It was 1968 and this was the first time I laid eyes on the spiv, Terry Clark. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the last.

Over the next 11 years, Clark morphed from small-time thug into kingpin of the “Mr Asia” syndicate, a murderous drug lord who ruled Auckland’s (and later Sydney’s) criminal underworld with unprecedented violence. He was responsible for importing massive quantities of Thai marijuana into New Zealand and then flooding both New Zealand and Australia with heroin. He is known to have killed, or ordered the killings of, at least six people. He is suspected of having killed six more, including my friend Norma.

In the 70s, I had two stints in prison — four years all up — and did 18 months alongside Clark during my first time inside. I got to know him well, and saw him on the outside until near the end of his criminal career.

But that night in the Civic foyer, Clark’s criminal career was mostly ahead of him. He punched the chubby man’s face repeatedly until his opponent pulled a knife.

I was taken aback — knives were rarely seen in fights back then — and my mates, seasoned street fighters in their teens and early 20s, were, too. Chubby’s arm was right in front of me and, without thinking, I seized it and held on tight. Ted Tamariki, one of my group, also grabbed him.

“Drop the knife and we’ll let you go,” I said. No response.

“Come on, drop the knife you stupid little prick,” I heard someone say.

Tamariki and I were trying, without success, to twist his arm so he’d drop the weapon.

“Drop the knife now and we’ll let you go before the cops get you,” I whispered as the crowd gave way to a couple of police officers who wrestled him to the ground.

What stuck in my mind was that Clark, who had thin, slicked-back sandy hair and dark bags under his eyes, was the picture of a criminal. Yet he had disappeared seamlessly into the crowd.

His appearance had nothing in common with the cherubic face of Matthew Newton, the Australian actor who played him in the 2009 television series, Underbelly: A Tale of Two Cities. Clark claimed he was once dragged home from a party by a woman who wanted to have sex with him because, she said, “You are the most depraved-looking man I have ever met.”

Three years after our paths first crossed at the Civic, I encountered Clark again — this time in Wi Tako (now Rimutaka) Prison, near Wellington. I had become addicted to hard drugs in 1969 and was doing time for pharmacy burglary, while Clark had been found guilty of car conversion and was serving four years.

I enjoyed teasing him about his sinister appearance. Joining the fun was fellow inmate Errol Hincksman, later characterised as Clark’s right-hand man and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment after a trial at London’s Old Bailey for drug importing.

“Terry,” I’d say, “you’ve got a boob head [a term used by inmates at that time to describe themselves, “boob” being prison]. You’ll never be a czar of crime because they’ll take one look at you and arrest you.”

Hincksman labelled Clark “Mr Sin”, an expression he’d picked up from Sydney’s tabloid papers. It was soon shortened, simply, to “Sin”. I had heard about Clark before I reached Wi Tako. Graham “Shaky” Wise, a member of Auckland’s small circle of hard-drug users in the 1960s, asked me some months before my first imprisonment, “Have you met Norma Fleet’s boyfriend?”

“No.”

“Well, watch out for him, he’s a nark.”

Not long after arriving at Wi Tako, I established that Clark was not only Norma’s boyfriend, but also the spiv I’d seen at the Civic (he had taken up with Norma in 1970, after splitting up with his first wife, and married her in the prison chapel three years later).

“Little prick kept putting his feet up on the top of the seat and kicking the back of my wife’s head during the movie,” was Clark’s explanation for the beating he had dished out to Chubby.

Despite his appearance, Clark had the superficial charm that apparently characterises most sociopaths. I don’t think any of his fellow inmates took him seriously, although he certainly knew a bit about crime.

Early in his stretch, he started teaching a group of us how to cheat at poker. He claimed to have made money from running poker games for freezing workers at Southdown and Westfield, the big abattoirs in Otahuhu.

In return, he was curious about drugs in general, and hard drugs in particular.

There was a small group of drug users in Wi Tako: Clark; Malcolm, a young guy who’d been sentenced to six months on a minor LSD charge; Little Mike, who I knew from Auckland; Wellingtonian Barney; Dave, who I knew from school; Melbourne street-schooled Henry Dean; and me.

Clark didn’t mind injecting opiates in prison but swore he’d never use them once freed (a vow he kept), and sneered at addicts for their weakness.

Clark consumed large quantities of the hypnotic drug Mandrax, or Quaaludes as they were later known. He didn’t mind injecting opiates in prison but swore he’d never use them once freed (a vow he kept), and sneered at addicts for their weakness. Hincksman, or “Inky” as he was known on the drug scene, was stylish, with a sly sense of humour. We became mates.

Our group inherited an old record player from a previous set of inmates who’d apparently set up a musical appreciation society. Soon, acid trips started flooding into the jail and we’d sit in a small room upstairs in the admin block, listening to rock music, stoned out of our heads.

After six weeks inside, every inmate was offered redemption of a sort — eligibility for Sunday parole with a Christian family in Upper Hutt, to enjoy lunch and then go to church with them. I couldn’t work out why Clark was taking part.

I was perplexed when he confessed he’d taken a couple of LSD trips one Sunday morning (he took pride in how much he could handle), and given one to his accompanying cellmate, another Terry. Terry 2 had never taken acid before and, as the trip came on during the parole visit, began pouring himself a cuppa. He kept pouring, entranced, as the tea overflowed the cup, then the saucer, and finally the table. Clark had been forced to clean it up. Not long after, Terry 2 flung his cake on the floor, screaming. He’d seen maggots writhing in it.

Then he felt ill and wanted to lie down, but because his perception of time was warped by the acid, he ran out of the room and was back seconds later, claiming he felt better.

“I had to tell them we’d taken acid,” Clark confided.

“Why would you do that?” I asked. “You’re more than capable of coming up with some line about him being unhinged. Anyway, that just about proves it, doesn’t it?”

Later, I discovered Clark had been moving from one parole family to another, finding out when they attended church, and using other parolees as extra sets of “eyes”. He’d stumbled on a Catholic couple he could manipulate into giving him their car on Sundays. He would use it burgle other parole families’ houses while they were at church, selling their TVs and stereos in Wellington the same day.

He had a remarkable relationship with at least one of the screws, who he’d managed to corrupt. But most of all, he had big ideas.

He was always telling fantastic yarns that none of us believed. We saw him as little more than a fellow fantasist.

He became friendly with the mother of one of his cellmates. I’d see him having animated conversations with her and her son, known as “Tubbs”, at visiting times.

One day, he came into my cell, closed the door, and pulled some pethedine tablets from his pocket.

A few nights later he returned to my cell in a panic. “I can’t get Clive to come across with the peth,” he said. It seemed Clive, an inoffensive-looking inmate who was on work parole, had been picking up peth for Clark from Tubbs’ mum. The arrangement had been made after Clark discovered she had the drug and convinced her the prison medic, Dr Hogg, would do nothing about his severe toothache.

Trouble was, Clark explained, Clive now wanted to try the drug and wouldn’t part with the pills.

“What are we going to do?” asked Clark, “There’s not enough for three of us.”

I thought for a moment. Bob Pilling, a middle-aged inmate who looked like a character from a Don Murray cartoon in Mad magazine, had been prescribed sleeping pills by Hogg. “Pilling’s got sodium amytal in his peter [cell],” I replied. “Tell him you need some to get to sleep, then tell Clive you’ll give him some peth but you need to grind it up first.

“Take the peth away, snooker it somewhere, open the amytal capsules you’ve got from Pilling and put the powder in a street packet (a small folded-up paper package). Take it back to Clive’s slot, mix it up in front of him and then hit him up. We’ll use the peth while he’s blobbed out.”

Believers in karma would say we got what was coming. Not long after, as I was walking up the steps to the medical block, a tall and powerful screw known as “The Bog” came out with an unconscious, jaundiced Clark in his arms. He looked like a small rag doll.

He was diagnosed with hepatitis B and rushed to hospital. Days later, I had viral hepatitis for the second time in a year.

The life and crimes of Terry Clark

? 1971 Clark sentenced to four years and three months for car conversion. (He tells fellow inmates it was for safecracking.)

? 1973 Released from Wi Tako (now Rimutaka) Prison after serving less than two-thirds of his sentence.

? 1973–1974 Gradually takes over the Mr Asia drug-importing gang in Auckland.

? 1975 Skips bail on a heroin-importing charge. Becomes a leading drug supplier in Australasia, flooding Sydney, Melbourne and New Zealand cities with high-grade Thai heroin.

? 1979 Arrested on the Gold Coast and extradited to New Zealand. Has the trial venue moved to Wellington and is acquitted of heroin-importing charges. Returns to Australia before the bodies of associates Doug and Isabelle Wilson are discovered in a shallow grave in Melbourne’s sand belt. Clark flees to England with Errol Hincksman and forces fellow Mr Asia gang member Andrew Maher to murder Maher’s best friend, Marty Johnstone, and mutilate his body. Johnstone’s handless corpse is found accidentally in a Lancashire quarry by divers. Police raid Clark’s flat in Knightsbridge, London. He is charged with the contract killing of Marty Johnstone and sentenced to life imprisonment.

? 1983 Clark dies of suspected heart failure in Pankhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight.

Rumours swirled of a big drug deal on the outside that Clark and other inmates were organising. I was in the yard one Sunday when Barney came back from weekend parole. He’d been sitting in a car on Lambton Quay in Wellington, outside Barrett’s Hotel, earmarked as the place where the money would change hands. Trevor, his mate from the outside and the drugs end of the deal, had carried a bundle containing hundreds of mescalin tablets upstairs.

As Barney waited, an unmarked HQ Holden pulled up and Wellington police drug squad boss “Cockie” Thompson and his troops ran into the hotel. Barney got himself back to prison as fast as he could. Trevor was arrested and later given five years’ jail, while the “money” man turned out to be one of the cleaning staff at Wi Tako.

Clark found other ways to maintain supply, getting a job as an upholsterer in the new workshops that had been built beside the original Wi Tako concrete rectangle.

Clive turned up in grey overalls one day, hopped out of a van, strolled inside and handed Clark a big paper bag full of pharmaceutical drugs. It was that easy.

I was freed after 18 months inside. Clark, despite his longer sentence, was already out and I spent the next weekend with him and Norma at the White Heron hotel in Kilbirnie. He was obsessed with the “classy” hotel chain.

On Friday night, I travelled north to Bulls with Clive. We broke into a pharmacy in the early hours of the morning and, following Clark’s advice, fired a nail gun into the safe lock. The pin, he claimed, would smash the barrel of the lock into the safe. In fact, it lodged in the keyhole and the barrel didn’t shift.

The next night Clive and Clark cracked a safe at a business they had heard held heaps of cash. It turned out to be an antiquated “tank” with big hinges, solid locking pins, and thick steel plate at the front and sides. The flaw was a tinny back, which you could knock out with an axe.

Clive and Clark used a gas torch, and the sawdust packing between the exterior wall and the flimsy inner cabinet caught fire, so they had to dowse it with a fire hose. Their haul was only a couple of hundred damp dollars.

That didn’t stop Clark from picking up the Dominion on Monday morning and braying, “Very professional, they said about our job. Not like yours, amateurish — very amateurish, it says here.”

While Clark and Clive were off “working”, Norma and I dropped acid. Later that evening, Hincksman called in with some Palfium, a powerful narcotic, and we hit it up on top of the LSD. It turned out to be a diabolical cocktail.

The Palfium kept sending me into a “nod”, but instead of the normal warm, peaceful dreams, I had literal visions of hell. I would snap out of these nightmares, sweating, and try desperately to stay awake, only to experience damnation again within minutes.

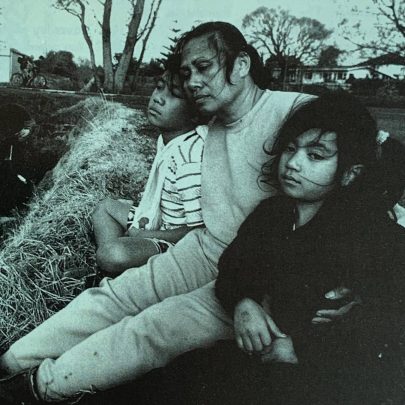

Norma, meanwhile, described her descent into drug addiction; how, aged just 15 and on her way home from school, she’d been kidnapped by an infamous criminal and addict, taken to his flat, injected with heroin and raped. After recounting this, she started nodding off too, only to snap out of her stoned state, shrieking.

Clark returned that morning and had sex with Norma in front of me. She taunted him afterwards because he didn’t get it up again almost immediately. “Come on, Terry, let’s see some more action,” she said.

I saw Clark several more times after that. He and Bob Pilling turned up uninvited at my registry-office marriage to my first wife, Nadine, in Lower Hutt, about a year after I got out of Wi Tako.

“Never thought I’d see this,” he snorted.

Some months later, he was there when I visited Clive at his Glenmore St flat with my baby daughter, Alexia.

“Now this is hard to believe — a child. Oh, it’s a little Jim,” he said, taking a good look, then grabbing Alexia, lifting her up and putting her on his knee. They seemed to like each other and she was soon smiling and giggling.

But, not long after, we parted ways.

One evening, there was a knock on the back door of our Upper Hutt cottage. Nadine opened it and pudgy Dave came in with a smirk on his face. Clark was behind him. They rolled a joint as though conferring an honour. A little later, Clark asked, “Can I leave some stereo gear here?”

I didn’t have to ask if it was “hot”.

“How long?”

“I’ll get it tomorrow.”

“And if not, the day or week after,” I replied. He pulled a sour face.

“I’m trying to go straight, Terry,” I told him. I expected some retort, but he just muttered and then left.

Later that week, Nadine rang Norma.

“If that stuff isn’t out of the house tomorrow, I’m throwing it in the Hutt River,” she said. The stereo system was gone the next day.

In 1979, I visited Clive, who was now flatting in Te Aro. Clark, his new wife, Maria, and their young daughter were among the crowd in the living room. They were celebrating Clark’s acquittal on a heroin-importing charge that day. He’d managed to have the trial shifted from Auckland to the High Court in Wellington.

I asked how he got off the importing charge. “I paid a quarter of a million,” he claimed.

We talked a bit about the Wi Tako days.

“Do you know where I can get some coke?” he asked.

“I’ve got some on me, actually.”

He was a slightly more suave version of the old Clark, minus the duck’s tail and better dressed. He’d allegedly had plastic surgery but was still instantly recognisable.

“Remember that bet in Wi Tako?” I asked. “An ounce of heroin or chemist’s gear to the equivalent that I’d be back inside within six months. Well, it was two-and-a-half years.”

“Yeah, I vaguely remember that,” he replied, looking slightly annoyed. “I’ll have it sent down with the next shipment.”

“So, are you going to stick around for a while?” I asked.

“Nah, I’m back off to Australia,” he said. “I’m not staying here with all that Mr North, South, East and West shit.”

I didn’t realise he was talking about journalist Pat Booth’s famed investigation for the Auckland Star, since little of it had filtered through to Wellington.

“I thought you’d been deported,” I said. “How are you going to get back in?”

“False passports.” (He explained he was employing a variant of the Day of the Jackal routine, using the birth details of a dead person.)

“Remember your mate Mike? I ran across him in Sydney and gave him a 10-gram bag to sell… he never came back.”

“That’s shameful, Terry, ripping you off for a miserable 10 grams,” I replied.

“Yes, and that’s why you’ve never worked for me,” he concluded. “I don’t trust you.”

Needless to say, the smack never turned up. I wasn’t grateful at the time, but I am now.

Only a few months later, I saw a couple of mugshots in a Dominion yarn about an Australasian police hunt, following the discovery of the bodies of Doug and Isabelle Wilson in a shallow grave. One of the mugs was Clark’s. Not long after, he and Hincksman were arrested in London: Clark for the murder of the original “Mr Asia”, his friend Marty Johnstone, and for importing heroin; and Hincksman on heroin charges.

I stopped drinking around that time, and gave up hard drugs completely 18 months later. I’m glad I never worked for Clark, for the sake of both my conscience and, more importantly, survival.

Years later, Hincksman told me that the night before they were arrested, Clark, primed on coke, had told him, “I wish I’d gone down a different path,” then added, “But now I’m on it, I have to admit I enjoy it.”

He had shown Hincksman a list of the people he’d killed. It was far longer than the six known victims. Then he’d produced another list — of those he intended to kill. It contained our mate Henry Dean’s name.

Where are they now?

? Norma Fleet died of a heroin overdose in the late 1970s, possibly administered by Terry Clark.

? Henry Dean was stabbed to death in a pub fight in Taupo in 1990.

? Errol Hincksman died of pneumonia in 2013.

? Barney has been clean and sober for several decades.

? Malcolm gave up drugs many years ago and became a psychologist.

? Dave runs a small business.

? Little Mike‘s last-known address was a commune in Australia.

? Clive lives quietly in the country.

? Jim Mahoney has been clean and sober for nearly three decades. He has worked as a publisher, editor, subeditor and journalist and is writing a book about his drug years.