Feb 15, 2024 Politics

Six years ago, business and the bureaucracy were ready to go along with a bold new social-democratic experiment. Capitalism, Jacinda Ardern told us, had been “a blatant failure” in reducing child poverty, her number-one objective. “Far too many New Zealanders,” her deputy, Winston Peters, declared, “have come to view today’s capitalism, not as their friend, but as their foe.” He promised “capitalism with a human face”.

Three years later, Ardern became the first prime minister since 1951 to win a majority of the vote. She might have done anything she wanted, but it turned out she couldn’t. Her successor, Chris Hipkins, had the perfect opportunity to do better, with Grant Robertson and David Parker handing him their innovative wealth tax policy, which would also have delivered $20 a week in tax cuts to everyone, including the very lowest paid. It would have been an election winner, but Hipkins was too scared to emulate Labour heroes Michael Joseph Savage, Peter Fraser and Walter Nash, or even David Lange and Roger Douglas, in boldly doing what he believed New Zealand needed. Hopes of a more progressive tax system — plus basic management fiascos like KiwiBuild, Te Pūkenga, Oranga Tamariki and, of course, Auckland Light Rail — died along with dreams of a new Sweden of the South Pacific.

If the Ardern–Hipkins government is remembered at all, it will be for Ardern’s initial response to the Christchurch terrorist attack, leadership through the first Covid lockdown and foreign-policy tilt back to Australia, the United States and NATO. But even those legacies were blemished by the gun buyback doing little more than arm criminal gangs and the delayed vaccine rollout necessitating the miserable 2021 lockdown and heartbreaking border controls.

In 2023, around a half million voters who backed Labour and the Greens in 2020 switched to National, Act or New Zealand First. If the red side can’t give us Sweden of the South Pacific, they seemed to be saying, let’s see if the blue team is up to giving Singapore of the South Pacific a go.

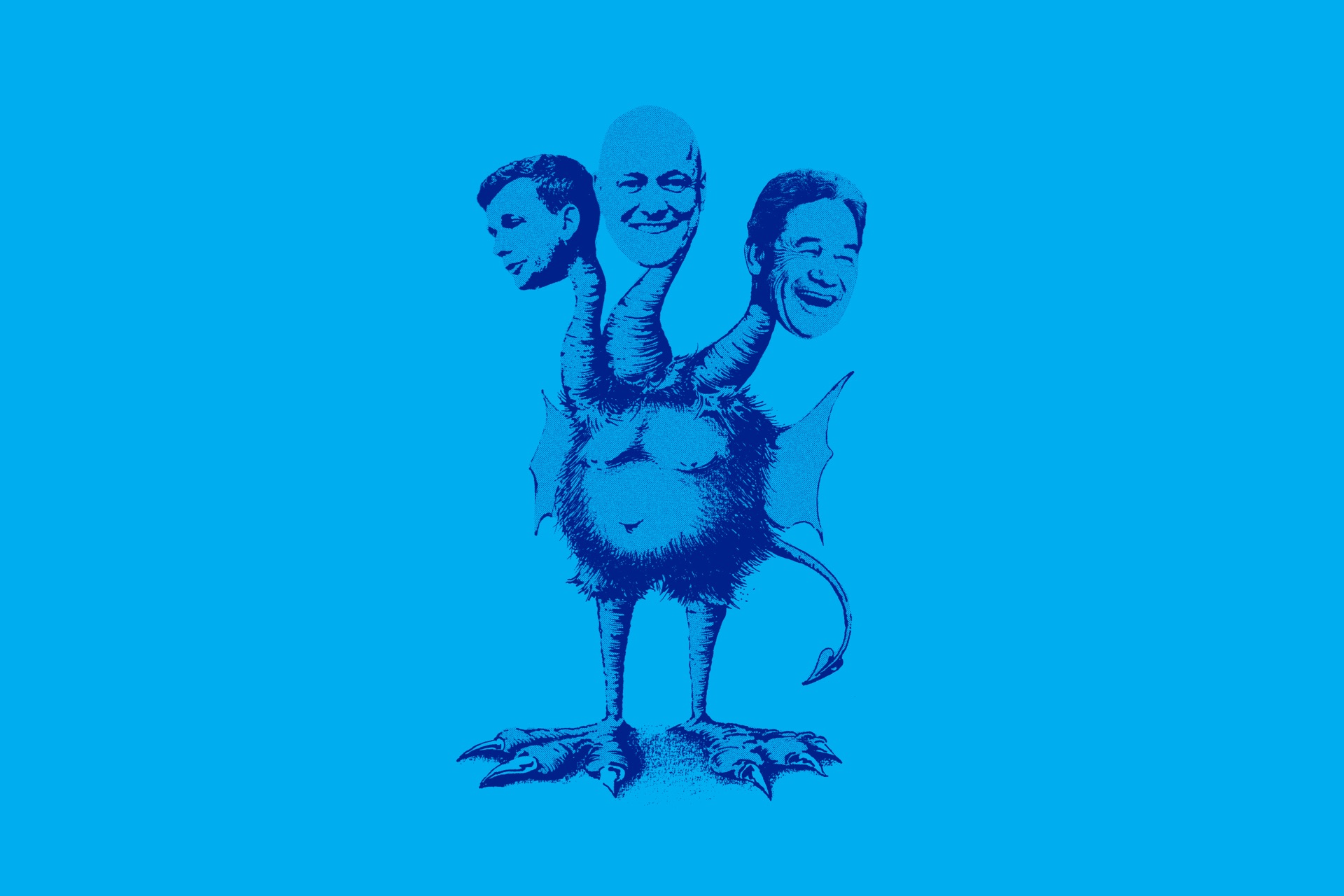

Depending on how wet or dry they are, those on the right lamented for somewhere between six and 27 years that MMP can’t deliver the governments they want. That complaint no longer holds. The unmitigated failure of the Ardern–Hipkins circus served up New Zealand’s most right-wing government since 1993 — much to the surprise of National, Act and NZ First loyalists alike. Those on the left may be appalled, but the Luxon government might be what’s needed for a much-needed correction, across several domains.

The most general point, which should please everyone across the political spectrum, is that the new coalition will hopefully prove that elections can make a difference; that competent ministers with clear objectives can get the Wellington bureaucracy to deliver what they want — quickly, and without needing ever-more elaborate working groups, commissions and specialist government agencies.

Likewise, a decent cull of the Wellington bureaucracy should be applauded by everyone, whether you want to take the money back for tax cuts and naval ships, or schools and hospitals. No one, not even the usually reflexively left-wing teacher unions, understands why staff at the Ministry of Education increased by 55% to 4311 full-time equivalents since Labour took office, compared with just a 5% increase in teacher numbers.

Staff in the Key government’s great bureaucratic folly, the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment, ballooned from around 3700 to more than 6100 during Labour’s term. More than 10,000 people now ‘work’ in those two Wellington ministries alone, yet New Zealand’s performance in education, business, innovation and high-productivity jobs has gone backwards. Quite why we need a Ministry for the Environment, a Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment and a Climate Change Commission, all three of which hire people to review one another’s work, has never been explained. No one, not least Māori, will end up missing the Māori Health Authority, which will have done no more for Māori heath than MBIE has done for economic growth.

More contentious is the coalition’s back-to-basics plans for schools, but defenders of existing far-left constructivist pedagogies can hardly point to any successes. Encouraging the private sector to open charter schools outside the official dumbed-down New Zealand curriculum and qualifications systems, and allowing state schools to join them, will at least provide a greater menu of ideas for what might be effective, including with different communities.

Acknowledging those who feel threatened by the speed with which te reo Māori has been adopted — and Parliament being more deliberate when it references the principles of the Treaty/te Tiriti in legislation — will be worthwhile if that helps protect the overall progress in the historical and contemporary Treaty-settlement process since 1975 and the genuine recognition and application of te ao Māori through society. National is proud enough of its leadership role in those areas since 1990 that it won’t allow Act or NZ First to bugger things up.

Likewise, NZ First stopping National from introducing $20 billion of new foreign demand into the housing market — and Act vetoing the more general fiscal irresponsibility of its tax package — means house prices, inflation and interest rates will be lower than they would have been if National had been left to its own devices. Labour’s mistake of thinking the Reserve Bank should worry about unemployment as well as inflation will keep both lower in the medium term.

Building on Ardern’s success, Christopher Luxon and Winston Peters will lock in the realignment with Australia and NATO. To reduce economic dependence on China, Luxon promises his trade minister, Todd McClay, will complete a free-trade agreement with India before the next election.

If the coalition invests in infrastructure the way Lee Kuan Yew did in Singapore in the 1960s and 1970s — and finds a way to stop the blatant price gouging by construction companies that makes building a road or railway in New Zealand costlier than anywhere else in the developed world — all this might even deliver a better-educated population, a more efficient and productive economy, higher wages, lower prices and less inequality and division.

Of course, it may not. In which case, it couldn’t hurt Labour to do a bit more work on how it would implement the Swedish option the next time it’s in government than it bothered to get around to from 2008 to 2017.