Jun 22, 2021 Restaurants

The kids on the North Shore used to call my old high school Rangitokyo. Back then, Asians made up less than 20% of the roll and, of that, most were Chinese and Korean. Despite that, it felt like our physical presence in the suburbs where I lived was muted; our nearest town didn’t have a single Chinese restaurant. My family travelled outwards, to Northcote or Howick or Ōtāhuhu, to browse the aisles of Tai Ping, stock up on that one toothpaste from back home (Darlie), and sit and soak in the harsh barks of Cantonese.

Things are changing — fast. Brand-new developments have been hammered into the Albany landscape by Chinese developers to serve the growing immigrant community. (I like to tell people that in some parts of the North Shore, the demographics have even flipped: pockets, like the McMansion-ridden Pinehill, are now 68% Asian.) There are empty shops for lease advertised solely in Chinese; storefronts without a single word of English; restaurants where you’ll be handed a Chinese-only menu; bakeries selling sponge-based, taro-cream-filled birthday cakes; aisles and aisles of imported goods from home, all arriving with the subtlety of an alien spaceship landing on the Skytower in the middle of a workday. And I love them.

In an essay for the Lucky Peach food-writing journal, Hua Hsu wrote on the concept of suburban Chinatowns, spacious communities where Chinese-Americans could run away from the tourist-created subsistence of “Chinatown” (I mean, Oriental- font Chinatown) and incubate a new strain of Chinese-American culture — not a rejection of assimilation, but a new kind. That’s kind of what’s happening in Albany, spurred on by a decades-long influx of affluent Chinese immigrants who, despite increasing regional diversity, have a baseline cultural commonality and desire to freely chat in Chinese to their hairdresser and eat tripe in steaming soups.

The first-ever Chinese restaurant in Auckland likely opened in the late 1800s. New Zealand Geographic described such eateries as having been around “since the very first days of Chinese settlement in the goldfields”, mainly in low-rent areas, shrouded in the corners away from society. Racism ensured that the clientele was mostly Asian. It was only after the Second World War that non-Chinese diners started to patronise the restaurants, congregated in “ethnic precincts” like Auckland’s Greys Avenue, which was famous for its opium dens and known to the local Cantonese as “Tong Yan Gaai”. There was even a restaurant in the same building on Hobson St that Wah Lee’s occupies, a happy continuation of Auckland-Chinese lineage. And perhaps the best-known Chinese restaurant of all, often credited as being the first in Tāmaki Makaurau, was The Orient (or New Orient), in the Strand Arcade between Queen St and Elliott St, which opened in the 1970s and closed in 2010.

All of these likely served Cantonese food, with various concessions to the not-yet-adjusted New Zealand palette (everything fried, everything saucy). Cantonese food broadly includes the cuisine of the Guangdong province, specifically Guangzhou. That’s where the first Chinese migrants, usually poor, including those early gold miners, came to New Zealand from. Many years later, in the 1990s, New Zealand implemented a merit-based immigration system, meaning Chinese people arrived from all over, usually well educated, skilled, and with capital to invest. This wave, and the one after it, saw an increase in people moving from what we Chinese call “the Mainland”, where residents mainly speak Mandarin instead of Cantonese. In 2018, there were 171,309 Chinese people living in Auckland, about 69% of New Zealand’s entire Chinese population. This, plus a significant Chinese international student population (in 2018, 41% of all international students were from China) meant that there was now a pretty strong economic case to just… keep it within the family. And not just that, but restaurateurs could now expand beyond “everything fried, everything saucy”. Chinese cuisine became regional, baby.

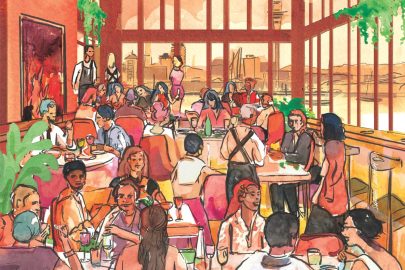

A precinct in Albany’s Corinthian Drive — the Albany Cuisine Centre — is a microcosm of a wider demographic shift: a move away from one monolithic understanding of“Chinese”. It flies the New Zealand flag alongside the Chinese one and is the biggest dining precinct on the North Shore: less tourist destination, more community hub. It’s a Chinatown, but it’s not Chinatown. It’s not even the only mini “ethno-suburb” of its kind; they’re in fact scattered all over the city (think Mt Albert, or Burswood, or Botany). Chinese people have historically been opposed to Chinatown branding mainly because the implied segregation is like a ghettoisation that recalls the Greys Ave of the past. But the best part of these new precincts is that they’re not necessarily special, or glitzy, or a political statement, or advertised as a way to performatively showcase our city’s diversity. They’re just a natural response to a changing Auckland. A new form of assimilation.

WHO’S IN THE SUBURB

KING MADE NOODLES

Cuisine: Lanzhou 兰州

Lanzhou is synonymous with hand-stretched beef noodles, and that’s the thing to order here, too: clear broth, white radish, thin slices of beef and, of course, pulled-to-order noodles which can go wide or slim. According to some sources, it’s entered the Chinese consciousness that girls prefer thin noodles while boys prefer wide, but we’d take that with a grain of salt.

YANG GUO FU

Cuisine: Malatang 麻辣烫

With Malatang, which is originally a street food, patrons can choose their own ingredients, which are then cooked communally in a hot pot. This new style of displaying ingredients on shelves and charging by weight became popular in Northern China in the 2010s. They can be cooked up in a soup or dry.

EDEN NOODLES

Cuisine: Sichuan 四川菜

Arguably the most famous spot in this precinct, Eden Noodles is a Sichuan restaurant, meaning the chefs liberally employ Sichuan peppercorns and chilli to pack a punch and give it that “ma la” numbing flavour. They also love to pickle and preserve, plus use broad-bean chilli paste (like in mapo dou fu) and fragrant spices, like cinnamon and star anise.

MY KITCHEN

Taiwanese 台湾菜

While not technically Chinese, Taiwanese food has similarities, due to the heavy influence of China. The cuisine also reflects the influence of Japan, a hangover from the 50 years that the island was ruled from Tokyo. In the West, the cuisine is particularly known for its gua baos and braised pork on rice: super fatty, herbal (medicinal, almost) and comforting.

PINYUE SHANGHAI STYLE

Cuisine: Shanghainese 上海菜

There’s a sweeter flavour profile here than in most other Chinese cuisines, with great snacks, like the shengjianbao (生煎 包). They’re pan-fried pork buns, fried so the bottom is all brown and crispy while the white dough stays soft.

YUE’S DUMPLING KITCHEN

Cuisine—Dalian 大连菜

Dalian is a coastal city, so there’s a lot of seafood on offer, including seafood dumplings. In Dalian, they use sea urechis (a sea worm), but in Yue’s, there’s mackerel, scallops and scampi.

ME & CHEF 米·湘

Cuisine—Hunanese 湘菜

Spice, spice, spice. “Hunanese are afraid of food that isn’t hot,” English writer and cook Fuchsia Dunlop once joked. Hunan cuisine is rich in chillies, including pickled, crispy peppers and flakes, and also heavily employs the savoury earthiness of fermentation. Try the pork spare ribs.

CHONGQING NOODLES

Cuisine: Chongqing 重庆

Chongqing is mostly known for being the birth city of hotpot, and is an offspring of Sichuan cuisine. At Chongqing Noodles , you can try the 88-degree special hotpot rice noodles with generous helpings of cloud-ear fungus and spicy-sour broths.

GOLDEN CITY

Cuisine: Northwestern, including Sichuan and Shaanxi 陕西菜

Shaanxi cuisine is famous for its wider and thicker noodles, with a chewier bite to them: doughy, almost, and immensely satisfying. They’re also often hand-sliced (meaning, knife-cut)

YUM YUM CAFE AND GRILL

Cuisine: Cantonese 广东菜

Here, the menu is laid out in true cha-chaan-teng style (diner- esque cafes), with healthy lashings of spam, ham, scrambled eggs, wonton noodles, macaroni, pork chops, and a weird section for exotic Western delicacies such as spaghetti and sirloin steak.

This story was supported by funding from the Asia New Zealand Foundation Te Whītau Tūhono.