Feb 19, 2016 Urban design

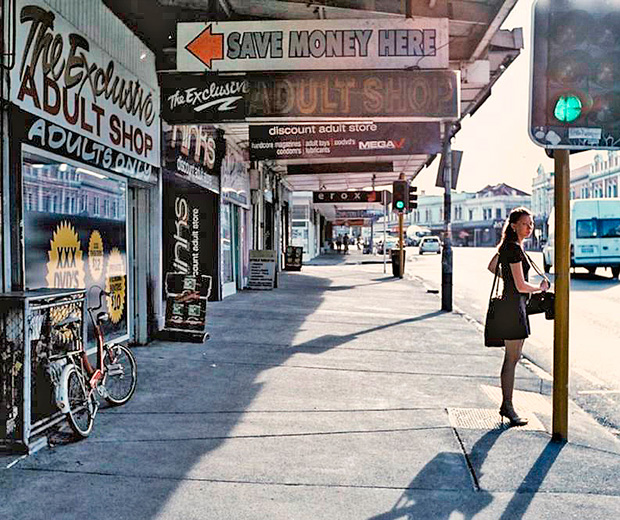

Change is coming to Auckland’s most colourful strip. Is Karangahape Rd set to become the new Ponsonby, as predicted by a prominent landlord and feared by small business owners?

This article first appeared in the January/February 2016 issue of Metro. Photos by Josh Griggs, Kate van der Drift and Joe Hockley.

The buzz on Karangahape Rd was already a roar by the time the Facebook account of St Kevins Arcade confirmed last June, in its usual breezy, upbeat style, that “we, the Arcade, have been sold”.

It went on: “This could be some fantastic news ensuring the Arcade remains the jewel in Auckland for many more future generations.”

The fact the arcade’s official voice felt the need to drop a conditional “could” into this news was telling. For more than 20 years — long enough for everyone to believe it was always thus — St Kevins Arcade had been home to K’ Rd’s bohemian soul.

In particular, Peter Hawkesby’s Alleluya Cafe at the back of the building had functioned for two decades as a kind of community lounge. For many people, and for various reasons, the arcade felt like home, even if they didn’t go there very often. And now it was turning into … Ponsonby Central.

It’s not clear where the phrase “the next Ponsonby Central” came from, but there could hardly have been a better way to distil K’ Rd’s perennial anxiety about being gentrified out of existence.

That anxiety was focused on St Kevins’ incoming owner, Paul Reid, a 35-year-old apartment trader known chiefly to the public for playing the rebellious teen Marshall Heywood on Shortland Street in the early 2000s. Reid paid his friend Murray Rose $10.142 million for the arcade — a price well above its 2014 CV of $7.8 million and an amount that raised eyebrows among other K’ Rd landlords.

Things did not start well. On the night Reid and Rose sealed the deal, they had a few drinks. Then they went to the Wine Cellar and had a few more.

The Wine Cellar is the much-loved and definitively grungy K’ Rd bar operated by Rohan Evans behind a door halfway down the arcade’s staircase to Myers Park, and what ensued was a classic culture-clash. Rose and Reid and their friends first baited, then got into a shouting match with, the alternative types clustered around the table in the bar’s smoking area.

They were eventually asked to leave — and Reid exited declaring he was buying the building and would “get rid of you left-wing creeps”. It was not Reid’s first alcohol-related scrape but he was reportedly mortified the following day.

Tourettes (aka Dominic Hoey), the local music scene’s ballsy, furious performance poet, responded with a poem called The New New Zealand:

And all the songs we wrote, and all the paint we spilt

All the shows we played for free, all of this was for you

All the shitty day jobs we worked that no one else would do

So we could follow our dreams at night like you told us to

So kill the fucking poor, the mad, the artists and the homeless

And all the streets will be spotless and smell like plastic roses

You can call this progress or you can call this cancer

Wanna say I don’t give a fuck but it makes me really anxious.

For Reid himself, he spat these lines:

I can’t hide forever beneath St Kevins Arcade

That asshole from Shortland Street wants to level the place

Reckons he’ll fix it up but I suspect he has terrible taste

And all his money can’t make up for his annoying fucking face.

Reid is nowhere near as wealthy as the man from whom he purchased the arcade, and he won’t and can’t level the place because it’s a protected building, but that’s by the by. What this is really about is that Karangahape Rd is undergoing the most swift and prodigious change since it was torn apart by the Southern Motorway in the 1960s. And no one knows how it’s going to turn out.

There is a “new Ponsonby Central” touted for the strip, but it’s not St Kevins. It’s number 309, an undistinguished 96-year-old building being transformed into an artisan food destination called K’ Rd Food Workshop — initially, the letting agent was Leah La Hood, who worked on Ponsonby Central.

It’s also the first place I lived, with a partner and new baby, when I returned from five years in London in 1991. Grant Fell, bass player for the Headless Chickens, and his stylist wife, Rachael Churchward, had set it up as their home, pulling down the false ceiling and using the boards to build rooms. This wasn’t strictly legal — it was difficult to live in commercial buildings in those days.

“There were lots of street kids, transvestites, prostitutes — all of whom we would deal with daily,” Fell recalls. “There were more than a few occasions when we had to push past someone to get in the front door, and a couple of times, knives got pulled.”

The country was in recession and K’ Rd was in flux. The closure of George Court’s building in the late 80s had finally ended the strip’s identity as the centre of department store shopping. It had been a long death — as far back as 1970, 40 local businesses had attempted to halt the decline by jointly funding an impossibly ugly carpark in Cross St.

On the other hand, the street had the kind of commerce in 1991 that it could do with now. There were two great fish shops, and Indian merchants with sacks of rice and flour piled high and sold cheap. The Norman Ng Building — constructed in 1926 as the marble-tiled entrance to the Mercury Theatre — was still home to the Ng family produce business. Ng, aged 82, told the Herald recently he recalled there once being 17 fruit shops on K’ Rd. In 2015, there are plenty of places to buy pre-loved clothes, a string of kebab shops offering shisha to kerbside customers, 10 liquor stores — but only the Lim Chhour supermarket to sell you a lettuce.

Something else was happening amid the decay of the early 90s. Brown kids, the children of generations of Pacific immigrants, converged from Manukau and Grey Lynn, rubbing shoulders with palagi bohemians. A new Auckland fermented and did much to inform Planet, the magazine Fell, Churchward and I published out of number 309.

My first editorial, in 1991, was infused with the spirit of the place and the time. “It’s the people running small ventures in the face of doom — shops, clubs, cafes, theatre companies and, yes, magazines like Planet — who are taking all the risks,” I wrote, defiantly, “while the big boys concentrate on their sinking lids.”

In some sense, it’s still home. I still care about it. Evans and Hawkesby both say they’ve seen the same thing at the Wine Cellar and Alleluya — regulars will disappear to the suburbs, perhaps for years, and then they come back.

It goes back further: before homosexual law reform, young men, alienated from their families, would drift to K’ Rd and find a caring “mother” among the drag queens who ran things. The domestic language said it all — this was home.

Hilary Ord and Janet Sergeant opened the Verona cafe at number 169 in 1992. It was their first business and it helped create the template for Auckland cafe culture. Verona’s own identity was so strong that it’s not markedly different now — the DJ decks still sit in the front window, facing onto the street. In 1998, they hired a teenager with purple hair to wash dishes. It was Paul Reid.

“I was washing dishes and one of the baristas was into acting and modelling and stuff and this casting guy came into Verona looking for interesting-looking people,” Reid recalls. “And so I kind of waved out and the barista introduced me and said, ‘Oh, they’re doing casting across the road for a TV2 commercial — do you want to do it?’”

Reid scored a featured extra role.

“I got $300 for a day’s work and free food, which I thought was just amazing. So I did that, and through that I ended up with an audition for Shortland Street. So I guess I have Verona to thank for leading me to acting work — and then the acting work to thank for the property work.”

The property work began one night at Borders bookshop on Queen St. The 21-year-old, flush with TV money, picked up a book by “property prosperity” guru Dolf de Roos. “It inspired me. It made sense. So I read a lot and took a bit of action.”

Paul Reid: “So while most actors were getting on the P in the weekends in 2002, I was out at Auckland open homes.”

His first investment was in Pt Chevalier in 2001: “That was a little one-beddy unit for $125,000. It was rented for $220 a week. And then I painted it and got $240 and I thought that was absolutely amazing — that was $1000 a year. Then I got it revalued six months after acquisition and it revalued at $155,000. I was just hooked. It was amazing — I’d made $30,000 in six months without really having to, you know, use my labour.

“So, while most actors were getting on the P in the weekends in 2002, I was out at Auckland open homes.”

By 2003, Reid owned six properties. In 2009, after a final bid for fame in Los Angeles with his band Rubicon (he also played in The D4 and Loves Ugly Children), he formalised his investment work into Iconicity, a property management company, then added other companies to form Icon Group. He says the companies have doubled their net worth every year since.

But when I arrive at Icon Group for our first interview in November, it is to a modest space. The main room, with half a dozen desks, is nice enough, but Reid’s own office is crummy: not much more than a desk, an iMac, an empty wine fridge and a loud air-conditioning vent.

This is the guy who drove a BMW convertible with the personalised plate APTMNT, who married his wife Rhiannon Cole in a helicopter over Las Vegas. It’s also the guy who kept his $80-a-week room in a Mt Eden warehouse while he was earning Shortland Street wages and buying and selling much nicer flats.

Reid is a hesitant interviewee and his move into commercial property in 2014 — and in particular into the culturally dense territory of K’ Rd — seems a big step up, in more ways than one.

“I think when you first do it it’s scary because the numbers are bigger,” he says. “Then you realise that it’s very similar and it’s almost easier in some respects because there’s less competition. I enjoy it more than the residential side.”

His plans for St Kevins? “Nothing radical. It’s just tidying up and re-leasing it to some better-quality tenants.”

Reid has hired architect Dom Glamuzina to handle the “tidying up”. For the time being the work on the arcade is limited to refurbishment — new tiles and fresh paint — but its Historic Places Trust B classification, which protects the exterior, allows the building to be expanded, perhaps upwards, in future.

Part of Reid’s plan has gone smoothly. In particular, Hawkesby — who had opened Alleluya in a “completely dead” St Kevins after returning from 10 years in Japan in 1994 — was ready to move on. Over time, he had consolidated the leases for the whole back section of the arcade — and they still had five years to run. He sold the leases to Reid for a substantial sum.

“I’ve told people, just keep coming,” says Hawkesby, sipping an afternoon beer at one of his tables. “First of all, you are business for whoever is operating in the arcade. If they ignore you, it is at their own peril… From what I see of the people Paul is introducing to the spaces, they are actually quite lovely young people who… already have an idea about the spirit of the arcade.”

Meanwhile, Rohan Evans quickly agreed with Reid on a new lease for the Wine Cellar. He says the first inkling he had that St Kevins was for sale was when Murray Rose announced he wasn’t signing a new lease, before disappearing overseas for several months.

By contrast, he says, negotiations with Reid were straightforward. “I had a meeting with him and James Kermode, who was doing a lot of the leasing negotiations, and he was very pleasant to deal with and he was quite straight-up. Which was quite refreshing compared to Murray, where quite often you weren’t quite sure what was actually being discussed.”

Some of the “better-quality” tenants weren’t so keen. The proposed rent was “just crazy”, according to one retailer approached by Kermode and Reid. “I said, ‘You won’t get anyone in there.’ And I think he’s realising that now.”

But the big hiccup was with Damaris and Renee Coulter, who in the past six years have made Coco’s Cantina both a fashionable place to eat and drink and a symbol of K’ Rd’s gritty culture. Approached at the behest of Glamuzina, the sisters got as far as a handshake at a “midnight meeting” in St Kevins.

“We didn’t want to be in another food court Ponsonby Central thing,” says Damaris. “We weren’t interested in being one of many players. Because our thing is vibe and setting the tone and service. And we knew that as soon as you chop up a communal space, you lose the communal aspects. So we wanted to be the dominant player in the space — and we would get told, ‘Yes you can,’ and then the plans would come through with another eatery here and another eatery there.

“It was this constant push-and-pull. Paul would say one thing and then the agent would say another thing. And in the end Renee said, ‘Fuck this, we’re not doing this, we’re not dealing with this.’”

Reid says “the whole point of this exercise” was to “activate” the arcade from morning till night, with a variety of offerings, rather than install a single dominant player to replace Alleluya.

“And that was why we couldn’t reach agreement — because they wanted to control the whole environment, they didn’t want to share. They were adamant they didn’t want it to be part of something like Ponsonby Central by having a variety of offerings.

“They just couldn’t share their toys, mate. They wanted to be the next Alleluya for the next 10 years and control that beautiful environment and not share it with other retailers. That was why we fell out.”

The Coulter sisters currently look across K’ Rd at a flurry of new commerce, which they acknowledge they have played a part in creating. The old Rising Sun Tavern has been split by developer Andy Davies into a backpackers’ lodge and a new hospitality space, its exact nature yet to be defined at the time of writing. Behind it, Davies is building a new 50-apartment block, perched above the motorway.

Nearby, the Las Vegas Strip Club is now owned by Gore Street Properties and has been redeveloped by Paul Franich and Lucien Law, who helped shape Britomart’s hospo scene. The pair launched it as Las Vegas, a nightclub and live performance venue, in late December. K’ Rd Food Workshop is a few doors down. Another big food and drink development is in the works at number 295.

Damaris Coulter wonders if they will embrace the K’ Rd community. “You realise when you’re actually here you can’t just plonk yourself down and say to all the ladies of the night and all the homeless people and all the people selling drugs, ‘Okay, we’re here, you can fuck off now.’ You’ve got to hold hands.

“So you say, ‘Do you want a cup of tea and can you watch my shop so that no one tags it?’ You integrate rather than take over. And a lot of people who come to K’ Rd today almost want to take over rather than integrate.”

The message may be getting through. Letting agent Leah La Hood was unabashed about gentrification — it was a key part of her pitch to potential tenants for the Food Workshop (one reported her enthusiasm for eventually “getting rid of the Polynesian bars” across the road). The promotional material she provided looked forward to an “incoming demographic” drawn from “upmarket apartment buildings” that would bring “hundreds of well-heeled city dwellers to the area”.

But La Hood has since left the project and Belinda Masfen of landlord Masfen Group (which bought the building in 2013 for just over a million dollars, well under its CV of $1.7 million) offers a notably different take: “I think K’ Rd has really nice character and that’s the appeal of K’ Rd — and we certainly don’t want to be seen to be changing any of that.

“We’ve talked to quite a lot of people about going in there and we just wanted to make sure that people were aware of the surroundings that they’re going

into, and about just bringing a different kind of customer up there. In saying that, we don’t want it to become Ponsonby. We’re really aware of what it is and

what it should be,” Masfen says.

The Food Workshop will open in April or May, initially with four operators producing food for consumption on and off the premises. The star will be Deanna Yang, the Lorde-endorsed entrepreneur who is bringing her milk-and-cookies concept cafe, Moustache, up from Wellesley St to take a front site. The upstairs floor has been let to interior designers Material Creative, who are moving from Parnell.

One of the biggest drivers for change on K’ Rd will be the “upmarket apartment buildings” touted by La Hood. They’re located mainly at the western end of the road — the area stranded when the motorway overbridge went in during 1970 and which, abandoned by “respectable” commerce, became the red-light district.

While sex workers still ply their trade on the corners, Tawera Group is converting the former Baycorp House on Hopetoun St into apartments priced from $309,000 to the penthouse’s $5 million.

After Fairfax Media moves out in June, the same developer will turn the former Telecom tower on Hereford St into 119 units with a focus on luxury (a buyer has already taken the “top front” as a single 400sqm apartment with 74sqm of deck).

Urba Residences, a 144-apartment block built by Conrad Properties in Howe St, is already sold and opening soon.

The site at the corner of K’ Rd and Gundry St, which had been earning about $120,000 a year as a carpark, sold last April for $5 million — the price suggests another apartment development.

Homes are going in elsewhere too. Near the eastern end of the road, Summit on Symonds, a 45-apartment conversion, is due for completion in May. The K’ Rd side of Newton Gully has been designated a Special Housing Area, with incentives for multi-unit dwellings.

Homes are going in elsewhere too. Near the eastern end of the road, Summit on Symonds, a 45-apartment conversion, is due for completion in May. The K’ Rd side of Newton Gully has been designated a Special Housing Area, with incentives for multi-unit dwellings.

This repopulation isn’t as rapid as the exodus of the 60s — when 50,000 local residents were displaced by the motorway — and it starts off a low base (the 2013 Census found only 3000 local residents). But the residential growth will be major, and it will drive more retail changes.

“K’ Rd will in my view be the next Ponsonby. But not for the next five or six years,” says Daniel Friedlander, whose family owns a swathe of properties on the strip, from the award-winning IronBank building at the Queen St end to long stretches of the Victorian and Edwardian buildings that characterise the ridge.

“People don’t like change. I accept that. But the area is changing and that’s what happens when a city grows. It’s one of the last areas in Auckland near the city that is changing. K’ Rd has been waiting for its time for the last 15 years — and now it’s slowly coming.”

There are other modes of living. Ian Hughes, another Shortland Street veteran, as both an actor and director, lives in a converted warehouse in Edinburgh St with his partner, Cass Avery, who is head of development at the digital agency Augusto, and their two children. They are friends with the man who sleeps rough under the church stairs across the road and have long made their peace with the remaining sex workers.

Hughes, who has lived on or about K’ Rd for 25 years, believes it would be a mistake to attribute the changes at the western end entirely to fancy apartments. Homosexual law reform in 1986 began the mainstreaming of gay culture. The Howe St toilets are no longer a gay hook-up spot. Urge, the beloved “bear” bar, closed in 2014, unable to meet its operating costs. While The Basement and the plush Centurian Spa still offer cruising opportunities in Canada and Pitt Sts respectively, the main-road bars Family and Eagle are straight-friendly and the gay-owned Caluzzi, which offers dinner and a drag show for $55, is a favourite for heterosexual hens’ nights.

Hughes believes the Prostitution Reform Act in 2003 also had an impact.

“It was fantastic for the street. It really got a lot of people off the street that didn’t need to be there and into parlours. All of the criminality that comes with people having to hide from the police went away. People could just get on with their lives and not have to live so brutally.”

If it was transport that broke K’ Rd, transport will also help reshape it when a City Rail Link station opens there in 2021. Dom Glamuzina, whose architecture practice is on the Cross St corner directly across from the rail link site (in one of a number of local buildings owned by Rose), acknowledges rail will have a significant impact on the area — and on the cheap rents that underpin the K’ Rd culture. But the unusual nature of the built environment may provide an answer, he says.

“There are some weird arcades down K’ Rd, weird back streets. All these little, strange spaces which have never been used. I think what might happen is that the main street might get a bit higher-end, but the backstreets will start to fill out. Cross St is a perfect example: there’s a lot of square metres of ‘other’ space off K’ Rd.”

A good example is Rebel Soul Records, opened last year by Tito Tafa in an unusual space at the back of the arcade in the Jasmax-designed Samoa House. Tafa’s bright paint job and kitsch decoration have brought alive the unevenly shaped room, which had been empty for more than a year. The shop overlooks Samoa House Lane — which harbours other hidden spaces — and he has begun using the building’s decommissioned fale for gigs.

A few doors down, The Hemp Store recently took a 10-year lease, after being kicked out of its former building in Victoria St when that became Reid’s first venture into commercial property. At one point, Reid offered owner Chris Fowlie his pick of spots in St Kevins. It was an odd idea and wouldn’t have worked, but Fowlie is delighted with where he ended up.

“K’ Rd has a much better vibe than downtown,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of people who run shops all over K’ Rd coming in to introduce themselves. We never, ever got that downtown. You’d be next to someone for 10 years and never know them.”

It’s not a given this will remain the case. When Jonty Rutherford took the lease on the Thirsty Dog pub on the Howe St corner in 2014, he narrowly beat a group that wanted to put in a Starbucks.

“In the daytime, we are a cosy local,” says Rutherford. “It doesn’t matter if the tables are a bit scratched — the food is really good. And we all know each other’s names. And at night we do gigs — everything from poetry to bluegrass to industrial goth metal.”

Perhaps it’s this locally engaged owner-operator culture that holds the key to K’ Rd, not the disappearing sex shops.

“That’s what keeps it different,” agrees Damaris Coulter. “Renee or I are always here — our community always sees us. That’s part of the reason we’ve had a community.”

Landlords have their part to play. Friedlander, whose family are regarded as unsentimental but honest and attentive landlords, says owner-operators need support: “A small owner-operator has a lease; it’s probably their first legal document and it’s their livelihood.”

Auckland Council, Damaris Coulter believes, isn’t helping. “We can’t even put a fuckin’ sandwich board out.”

Even getting an abandoned car removed from near Coco’s was an ordeal, she says. When there’s blood, shit or vomit to be cleaned up, they do it themselves.

She’d like to have a contact, just one person, at the council who is devoted to the interests of owner-operators.

The Karangahape Rd Plan 2014-2044, a lengthy, sincere and somewhat bland document developed by the Waitemata Local Board in consultation with the Karangahape Rd Business Association, contains nothing so practical. But it does affirm a commitment to the area as “the creative, edgy fringe of the city centre”.

The plan was adopted in late 2014 and has entered the thicket of plans that lead to the Auckland Plan. Twenty-eight times, it proposes to “explore” ideas — a symptom of the board’s relative lack of power. But perhaps its biggest challenge is the pace of change. Page 47 features a pedestrian bridge to a future cycleway on the disused motorway off-ramp. The cycleway is already open and the plaza at the east end of the bridge is already the site of Davies’ apartment block. The Gundry St corner named as one of “six key sites” will have been developed long before the plan translates to action.

The board’s desire to preserve K’ Rd’s built heritage is widely shared. Who would want to lose the country’s last three-storey Victorian block, opposite Howe St? But who will carry the cost of bringing it up to earthquake standard?

In the end, perhaps, locals would be pleased to have some proper public toilets.

A couple of days into December, on a Thursday evening, K’ Rd is a vision of what it might be. While nearly 1000 cyclists gather for a ride on the new Nelson St cycleway, the street has its groove on with a First Thursdays event.

The Superhero Second Line band swings its way west, east and back again. Short films from the NZ On Air-funded K’ Rd Stories project screen in nooks and crannies — bars, a barbershop, galleries. Crowds drift happily along. The only flaw seems to be that half the shops didn’t get the memo and have closed early.

The street works well when there are people on it. Back at the turn of the millennium, when K’ Rd’s club culture was ascendant (it has been hurt by a 2014 council licensing regime forcing bars and clubs to close by 3am), it was often a mad, happy scene.

When Flying Out — the distribution arm of the Flying Nun record label, which moved into the old Shaver Shop in 2015, along with its associated companies — staged a music festival across six venues in September, that worked too. The people who came for the shows also ate and drank there. The logical step would be to occasionally close the street to traffic, but this is not a favoured precinct like Federal St and that’s not going to happen.

Tonight, Carnivorous Plant Society, denizens of The Audio Foundation, which was granted the use of a basement in Poynton Tce in 2011, have come up the stairs to play their freak “cinematic jazz” in St Kevins Arcade. The place is packed, people are cheering and Reid is sitting, smiling, sharing a table and a bottle of wine with Rose.

Reid can afford to relax. Kermode has just signed off with the arcade’s long-running underground music venue Whammy Bar, which, along with 37 other St Kevins tenants (including more existing businesses than initially seemed likely), now has a long-term lease. Everyone’s rents are up, but the arcade looks cleaner and brighter than it has in years.

Reid can afford to relax. Kermode has just signed off with the arcade’s long-running underground music venue Whammy Bar, which, along with 37 other St Kevins tenants (including more existing businesses than initially seemed likely), now has a long-term lease. Everyone’s rents are up, but the arcade looks cleaner and brighter than it has in years.

Former Coco’s employee Emma Lyell has taken the Alleluya space with her partner, longtime Metro illustrator Tane Williams, for a new cafe, Personal Best. It will share the communal area, according to time of day, with just one other restaurant: Gemmayze Street, an “authentic Lebanese concept” by Samir Allen, who has worked at The Grove and Baduzzi and is a former resident of one of the arcade’s apartments. They’re set to open later in February.

Reid will call a few days later and acknowledges the project has been a learning experience: “You’re dealing with something that has its own character and soul, so it’s sensitive, yeah. It means so much to so many people. It’s finding that balance — improving it without alienating the existing client base and the businesses that are there. We’re getting there. It’s still a work in progress.”

Amid the First Thursdays hubbub, I bump into Hilary Ord, founder of the Verona (“I don’t get free drinks there any more — well, depending who’s on,” she says). Ord has just seen Reid, and congratulated him on his venture. “He said, ‘You fired me twice!’” she laughs.

What was he like back then? “Oh, he was a brat. He also said, ‘I bought this for my daughters.’”

So perhaps Reid, who has spent the past decade and a half doing-up-and-flicking-on, really is in it for the long term. And perhaps K’ Rd will change Paul Reid as much as Paul Reid changes K’ Rd.

Perhaps, like everyone else, he’ll have come home.

Main image: The Superhero Second Line band performing in K’ Rd during a “First Thursdays” gig in December. Kate van der Drift.