Feb 19, 2015 Urban design

At the design symposium Semi-Permanent in Auckland this year, “architectural delineator” Nat Cheshire gave an acclaimed talk. This is it.

This story was first published in the September 2014 issue of Metro. Photos by Jeremy Toth.

I work across sites that cover 10 hectares of this city’s core. Our studio has in the past three years built two dozen projects covering four city blocks in downtown Britomart. We have invented the emergent City Works Depot . We have built new buildings and old buildings and theatres and laboratories and offices and shops and dispensaries of social harm.

At some stage in the midst of assaulting the city, we also made two small houses in the countryside. This is one of them.

At the outset of this project I showed our clients a photo of an old, blackened, cast-iron Chinese teapot. I said we wanted to make them houses like that teapot.

We wanted to make houses that did not look like buildings. We wanted to make houses that had the silent potency of the unfamiliar. We wanted abstraction and tension and fear and love and hope and darkness and humility and the scent of burnt wood and anything but indoor-outdoor fucking flow.

I am not going to talk any longer about houses. I just wanted you to see this one because it is complicit in the Modernist revolution that wiped away 3000 years of near-linear evolution in art. In place of that slaughtered history, Modernism has laid before us unprecedented creative freedoms. It is our collective responsibility to continually and aggressively exploit those freedoms, and lead this culture boldly into its own future. In the face of your own extraordinary lives, I don’t know what else to offer you but my own. I am not an architect. But I am trying to make architecture.

My name is Nat Cheshire. I share a studio with 25 people who I love. We trained as architects. Now we design city blocks and teaspoons and edit menus and build websites and send light fittings to Italy. I have been gathering my thoughts on the transfiguration of our city, and the life our small studio has lived in the service of that transfiguration.

This is what I think.

THE CITY WITHOUT HOPE

This was once a city without hope. Auckland had suffered too long from diffusion. Its tiny population was smeared like thin, rank butter over a huge isthmus. Auckland was a city in title alone. In truth, it was barely a collection of villages. In truth, I didn’t believe in it any more than you did. In the void left by hope lives selfishness. Throughout my childhood it was selfishness that defined power in our city.

I grew up watching our city tear itself to pieces.

I grew up the son of one of the bravest architects this city has ever produced. I clambered over building sites and followed my dad around with a toy hammer and baby-sized tool belt.

Yet somehow I never thought what he and his comrades did was anything other than absurd and in any case impossibly painful. These few giants still swung clubs at this vile city and roared unwavering in its face. We were simply too broken to see what they were starting, or to believe that it was anything other than heroic martyrdom. They were superheroes without an audience. This was our fault, not theirs.

By the time I finished school, almost everyone had left this place.

This was once a city without hope.

I stayed. I stayed because I believed that upon the shoulders of those giants, ours might be the first generation to effect global change from this little place at the bottom of the world.

Motivated by rage and disdain, I tried to join their fight in the darkness, a child among angry men. I put on bow ties like a knight puts on armour.

I started a studio of two people in my parents’ spare bedroom. During the day I studied, during the night I worked. I was 19. I averaged $4.65 an hour over four years. I published nothing. I affected few. But I learnt. I worked furiously. I changed the lives of those for whom I worked. I believed that to be worth the pain and the exhaustion. I still do.

THE PHONE CALL

At 23, I closed my own office, to join my father’s new studio. I was terrified of working in his shadow, but exhilarated at the chance to wrestle with the opportunities through which he daily stalked. Our studio was six people. For five years I worked for Pip. He and his team fought long and hard to shape a master plan for Britomart. I struggled to keep up. I took comfort in an apartment I made that sought to make manifest the clarity I thought existed in architecture, if only architecture might listen to art. I pursued the delights of our craft and reeled at the chaotic exhilaration of building. I pursued abstraction and reduction and the energies of crystalline geometry and the bodily discomfort of an impossible object.

Then, one day, I got a phone call. It wasn’t for me. It was lunch time. I didn’t eat lunch. In the absence of the grown-ups, I raced down the hill and met a couple of Britomart’s development managers who were trying to corral an unbelievably hungry kid called Nick, from Milton.

This kid Nick wanted to make a big bar in the wrecked hulk of an old building. He could barely keep his fucking eyeballs still. He didn’t care about hope or darkness or romanticism or giants or children. He just cared about delivering the extraordinary to a city bloated on banality. He thought he could just punch a hole through Auckland. And really powerful people were taking him seriously.

Collectively, these looked like people who might yet have the strength and positioning to redefine everything about the way we work in this city.

They cared nothing for process or professionalism or authority. It wasn’t like these things were ignored. It was just like, for them, they did not exist. All that mattered was the extraordinary future. It seemed worth sacrificing almost everything to try to keep up.

THE BEGINNING OF EVERYTHING

I returned with charcoal in my hands. I worked through the night and tore his ideas to pieces and put them back together on a mountain of butcher’s paper. We met on Tuesday morning. He said, okay, fine I’ll think about it, but here’s this hotel idea that I’ve been working on, my architect doesn’t get it and keeps feeding me shit, and there’s no money, but you seem hungry so maybe you want to have a go at it. I asked him to sign a fee letter that would pay us if he went ahead and built our idea. He said no. He wrote me a letter back that said, in 100-point font: “Nat. I will not fuck you over.” That was all.

We ate lunch in his restaurant on Friday. I handed him a book we had made. It told a story about a new kind of hotel. He closed the book and said I had not been fucking around. I had not. I had not slept since Tuesday. He got me whisky and some chips.

At three o’clock, he phoned: “I just pitched our hotel to the owner of Britomart. He fucking loves it. He wants it open before the [Rugby] World Cup.” Within an hour the owner of Britomart called me himself. At five o’clock I stood in a boardroom with a man who built an entire city in Texas from the desert up. We looked out the window at nine blocks of downtown Auckland. He asked me what I had been doing. I felt that while the hotel had gotten me in the door, the real game was in the old buildings.

I looked out that window and tried to crystallise for him an image of our dream. I wanted him to see what we saw. I talked about what I believed Britomart had become, what I believed its most radiant future might yet be, and then the ways in which this kid from Milton with the shaky eyes would help us stride into that future.

He laughed and said okay, let’s build it. He looked at me funny. I guess he had already decided before I arrived. I felt small and exhilarated and a little bit sick. I left. We built it. I was 28. Our studio was 10 people.

Cafe Hanoi Auckland" width="623" height="415" />

Cafe Hanoi Auckland" width="623" height="415" />

THE DANGER OF EVERYTHING

We made a bar that became a bar and a restaurant, then became five storeys and two buildings of simultaneous adaptive transformation. In their pursuit I almost lost everything. I had always worked hard. Now I was meeting people who worked even harder. I lived in the city. I would wake and leave for work each day at four.

I picked my way through nightclub queues and vomit to work in the darkness before the phone rang. Often the phone rang anyway, and I would not even make it as far as the studio. The site consumed me for days at a time. All I had ever made was an apartment. Now I roamed an enormous dripping hulk, wielding millions of dollars’ worth of material and hard, brave labour. I barely slept.

At the apex of my delirium I found myself in an airplane toilet measuring the width of the room with my shoes and vomiting at the imminently-built errors my discoveries implied. In that toilet I discovered for the first time my own cliff-edge. I discovered later that if you know where that cliff-edge is, you can then use all of the space leading up to it, all of the time. I gleefully abused this knowledge.

But this is architecture. Architecture is art taken from the cotton wool of the gallery, where even a light switch is an intrusion, and dragged out into the most violent and chaotic commercial space I know of.

Architecture is standing in the middle of a dark studio at 4am weeping with rage at your own ineptitude and fear, and pushing through anyway, in order that that art might survive.

THE MIDDLE OF EVERYTHING

So we just built. We built like crazy in this rabbit warren of old brick and pigeon shit and timber harder than steel. We tore the thing apart with diggers and made a bar out of decadence and decay in equal measures. We set billion-dollar, hand-made glass mosaics amongst crumbling brick and filthy plaster. We made bars out of old bolt boxes and the kindling rippings from our waste timber. We turned underwater rubbish dumps into luxury. This was my first bar.

Simultaneously, we made a restaurant out of second-hand chairs and even worse plaster and this idea we had — called “humble special”. It was an idea that sought to unlock the free potentials of aged, distressed and humble objects by choreographing their decay, then setting them in tensile opposition with small moments of soft refinement. We wrote a script: A small door behind the bar opens onto a common service stair. At its bottom, a compressed, subterranean corridor of crumbling concrete and brick, punctuated by three small doors. The darkness is lifted only intermittently by fire-proof mining lights.

We figured that, if it was bad, we might as well make it really bad. There could only be a jewel at the end of a journey like this. So we made a jewel at the end. This was my first restaurant.

THE HANOI LESSON

During the day I spewed out drawings over the walls and fought furiously to get permission to trade. During the night I oiled steel bar stools and hung speakers and painted cabinetry and scraped the walls above Hanoi’s door to reveal this one little bit of Vietnamese green that by divine providence lay between layers three and four in a hundred years of accumulated beige.

Then one night we opened the doors.

It was a Tuesday or Wednesday. Outside was a wasteland of gravel. There was no PR, no advertising, no sign outside the door, no reviews. There was not yet, really, any Britomart. By eight o’clock that Friday night, there was a wait list of a hundred. People turned up at Hanoi and said “Two hours? Okay, put me on the list.”

Then 1885 opened.

Grown women queued the length of two blocks to fight their way in. They drank and fought and fucked and vomited all over our child.

We huddled around computer screens in a back-room coat cupboard, watching in awe as a thousand dollars scrolled by every minute. We reeled at the potential of what this might signal for our once-tired city. All of a sudden Auckland looked really, really hungry. Reverse emigration had flooded us with globally sophisticated denizens who had left cities like Tokyo and Melbourne and New York and Shanghai. They brought with them an appetite for the life they had left behind.

We realised in those first few nights that if you committed totally to delivering quality of experience above all other things, this city would eat you alive. It was like we had just opened a door, and our whole world had turned inside out through its aperture. Over and over, all people said was, “This does not feel like my city.” People imagined that in here, they were somewhere else. What was most exciting was that we were changing not just what this city was, but what it imagined it might yet become.

Imagination is hope. Hope is all we needed.

ACTION

In a situation like this, nothing is a sensible alternative to action. Theory and premeditation and care must be thrown aside in favour of commitment, speed and the stomach to survive in the violence that speed demands of you. In this jet-stream, building feels more like street fighting than architecture. We did not stop or breathe or sleep.

We felt like we had found a loophole in the matrix of the city.

We set out to take this fucking city back as fast as we could. We made bars out of old carparks and shipping containers and the surrounding dereliction. Five weeks in, I got another phone call.

It was my birthday. The kid from Milton said, “Happy birthday, to commemorate the event I had a baby. And you have to finish my bar.” I turned up on site at 4am the next morning. I did not leave for a month. Somehow I kept my part of the studio going. I wielded a nail gun and led a site of seasoned men and drunken bargirls waiting for a finished bar so they could serve liquor rather than drive power tools. I drove cherry pickers down empty Britomart streets at 3am. I lied to the authorities.

I lied so badly that when an officer turned his back I turned and sprinted into 1885, down to the basement, and locked myself in a toilet cubicle, lest he discover the extent of my deception and indict me on the spot.

I stayed in that cubicle for half an hour. Then I finished the kid’s bar.

We raced on. We built a whole block from refrigeration panels and perforated metalwork from some guys who make fire trucks. We made them, from first briefing to the switching on of the last LED, in barely 12 weeks.

We made restaurants out of poison and butcher’s paper and snakes and saints and skulls and upturned buckets and the sensuality of women with flowers in their hair.

We made offices out of mathematics and shops out of apple carts. We made salons out of fur and flowers. We made buildings out of paint and walls out of 2000 smashed plates. We hired maître d’s and picked flowers and lit candles and wrote menus and drove cherry pickers and wrote speeches and made guest lists for billionaires.

We tore at the professional boundaries of architecture, transgressing fields and abandoning professionalism outright. Hopped up on adrenaline and fear, it felt like we were changing the whole city. By the time of the Rugby World Cup, we had nine live construction sites in Britomart alone. If you were still in this game at the end, you could barely breathe.

Every Friday night, to try to stay alive, we would build ourselves a bar. Six of us kids from different worlds all fighting and failing side by side. Broken furniture and stolen candles and an iPhone with the volume turned up. Near pitch black. A tiny loading dock the floor; the pit of a lift shaft the bar. A wheelbarrow wheeled through back corridors into a heaving nightclub. Barrow filled with ice and champagne and liquor and glasses and sugar. Food run from the club and passed through a hatch. Cigars and furs and rags and fear and exhaustion. Our own “Drunk in Love”.

We called this IKTO. I Know The Owner. I learned in IKTO something important about loneliness. I made a diagram of it. It is an asterisk. The wedges between each line define a discipline.

Architect. Restaurateur. Developer. Physicist. Painter. Everything. The broad tails of those wedges are filled with the huge mass of each discipline’s practitioners. Their sharp, hardened tips define instead the rarefied space at the leading edge of each art. The harder you pursue that sharpened tip, the fewer those who can properly know you. But here, at the centre of this diagram, the fewest people are crammed together the tightest. Here, despite the incongruence of our respective arts, we find ourselves far closer to each other than to the regular body of our own professions.

Here, in the centre, there is camaraderie to be found in a mutual loneliness.

I turned 30. Our studio was 18 people. The air felt on fire.

THE NEXT BIG PROJECT

It was over. The Rugby World Cup. We didn’t really know it was on. We stopped making IKTO. Then we made it one last time, and put a till in it, and opened it. It was never the same.

We kept racing. A real estate agent introduced me to two really unusual carparking operators. They loved Britomart. They had bought a big carpark with some old sheds on it. The carpark just happened to comprise four hectares of central city, placed and scaled so as to bridge in one move the gulf between the city and Freemans Bay. They described their hopes. It was the Thursday before Easter.

I sat up all Easter and wrote everything I knew about the city and how it could be changed and why they should believe in that change. I sent it to them on Tuesday morning. I wrote 4000 words.

The last 80 read: “We won’t fuck around with urban design and arrows and axes. We will just outline the big gains to be made now, and then how these might be refined as the project develops. Then let’s just start. We will be setting out to make a project so successful that it energises the city as a whole, and so carefully balanced that it maintains that energy for decades more. We think City Works Depot has this potential. I’ll see you in an hour.”

I think they loved it. They bit down hard. We started immediately. We remade the City Works Depot in less time than it took us to get approval from a corporate client for a chair we had chosen for them. There was an extraordinary day when it just happened. I walked into a meeting with the owners. We sat and talked for several hours, trying to manage a contractor who was in crisis.

While we were in there, a blog appeared. We had these now. It included a brief notice about Al Brown’s new bagel shop out the front. I got up to walk out of the meeting and could barely get out the door. It was like a thousand people had arrived in an hour. There were queues 50 long reaching out almost every door — not just Al’s. People covered every surface we had made to sit on, and everything else too.

Where once there were a few solitary guys in beards pushing motorbikes around, now there heaved silk dresses and bespectacled hipster kids and corporate refugees of the offices that lined the ridge above us.

The place had hit its tipping point. It had both critical mass and bold unfamiliar quality. The city had noticed. It literally happened in an hour. It hasn’t stopped. The City Works Depot now exists. I still find that kind of shocking.

The difference for City Works Depot was that Britomart already existed. Britomart had become the monster against which not just this place but everything we were involved in seemed now to be measured. It had changed the way we understood the potential of our own city. We turned back to Britomart and said we needed to do to its days what we had already done to its nights. We needed to make it as good at 1pm on a Saturday afternoon as it was at 1am on a Saturday morning.

We started by fixing the thing we’d already made.

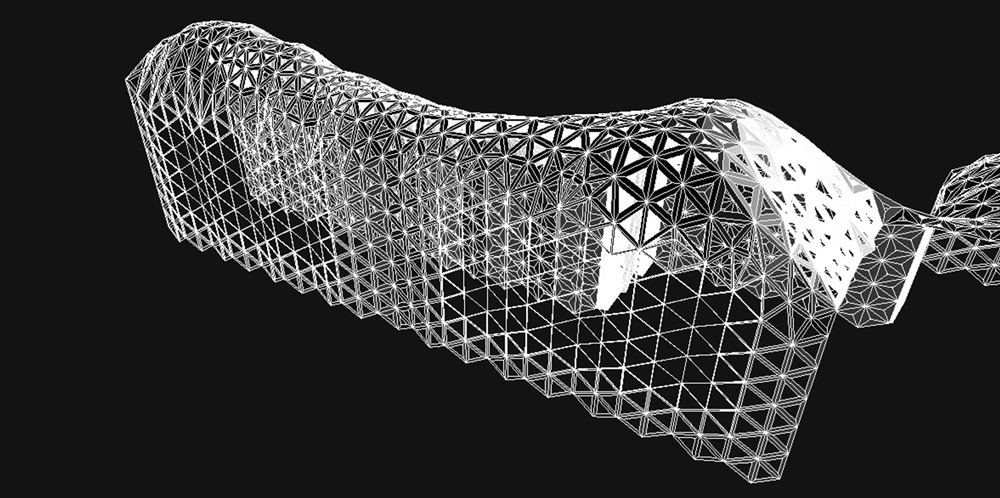

From there, we started on an idea for a whole city block

that became pavilions

that became a garden

that became a garden restaurant

that became a laneway

that became the aggregation of four rubbish rooms into a tiny unwieldy new tenancy

that became a scripted mathematical tool

that became a single net surface absorbing every retarded undulation into a singular fluid world

that became a parametrically defined system of contraction and dilation relative to its proximity to the transparency of windows and the opacity of those awful gib board walls

that became a fractal system derived from the Arabic mathematics of moucharaby

that became 1200 panels individually cut directly from the computers of our studio that became an ambition to deliver a completely immersive environment of transportative power within these little rubbish rooms

that became the manifestation of our delicate cave-like dreams into a finger-tip-scaled sensitivity that we hoped would quietly scream our commitment to the reconciliation of technology and humanity and above all make people feel deeply, bewilderingly excited in the otherwise familiar back streets of their own metropolis.

By now our studio was 24 people. It was hard to tell what all of them were doing. We had become so committed to the idea of the total environment that people were as likely to be dying fabric or stitching handbags as they were drawing buildings.

LESSONS

Enough. In 10 more years we will look back on this short period and not believe that so much could possibly have been changed so fast. Think back four years. There is no Britomart, no Wynyard Quarter, no Imperial Lane, no City Works Depot, no Osborne Lane, no Ponsonby Central, no Elliott or Lorne or Fort St shared spaces, no Q Theatre, no new City Art Gallery… There was barely an Auckland at all.

I have learnt three things about the mechanism of this kind of radical change.

First: that the simultaneous convergence of commercial benevolence, political mania and cultural sophistication is the sparkplug.

A few bold entrepreneurs pursuing quality collided with each other and competed in a model of development that looked more like benevolence than self-interest. A city council had just consolidated a long-impotent hydra into a single beast with the scale to make bold plans, the resources to execute them, and the nous to stay out of the way of a good thing. A GFC flooded the country with globally brilliant denizens fresh from Tokyo and New York, prepared to suffer almost anything in order to either produce or consume the quality of experience they had abandoned.

All three of these things happened at the same time. Their collision generated demand, supply and the political nous to recognise and keep clear of the beautiful mess that ensued. Their collision sparked an extraordinary environment of change.

Second: the accelerant of that change was the discovery of high-speed, small-step organic growth as an alternative to the arrogance of the autocrat’s master plan. You could see it first in our food and clothing. As our lives grew increasingly technologised we reflexed, demanding a counter-balance of archaic detail, hand-sourced provenance and personal participation. The city modelled its change on these same appetites. Every scrap of change in this town has been organic. That earlier list is defined without exception by projects that have been grown or grafted rather than made. Every new thing is now made from an old thing. Britomart, Wynyard Quarter, Imperial Lane — all of them. This is an age of improvisation.

The third thing: if you can get this far, the whole system becomes self-perpetuating. Extraordinary new spaces now open so quickly we cannot keep pace. They are so strong that they do not cannibalise each other, but reinforce each other.

They generate a culture of competitive brilliance. In the face of that culture, the weak and the uncommitted simply get slaughtered. This is a necessity. After three decades living in a city of weakness, I have no pity for those fallen.

THE FUTURE

We live in a small place in a time where smallness is no longer a constraint.

Instead, it is a conditioner for massive change. There are few places on Earth that one might change so radically, so fast. Almost none of them are in the West. We are politically and economically stable, geographically isolated, socially sophisticated, unencumbered by deep history and, as a consequence, nimble enough to turn on a dime. This is the opposite of the thunderous momentum of a global metropolis like Manhattan. We live instead in a place in which almost everything is enormously more malleable than it appears. We live in a place where the actions of the individual can yet affect the lives of the whole.

We must not waste this.

It should be dawning on us that at this moment of our maturation our great opportunity is not the resolution of national identity that has so burdened this last century of art. The idea of New Zealandness in art must die. We must be past this already. Fantails are birds and ferns are plants and rivers are water and farmers kill sheep so we can eat their bodies. It’s not that these things don’t matter. It’s just that there’s so much that matters more. What matters most now is only the work, in its own terms.

Abandon your metaphors. We need to understand that the work we make here must not just be good here. It must be good everywhere. Fuck it, it would already be good everywhere. Our opportunity now is to engineer a reflexive cultural imperialism: to use our little cities as the launchpads from which to reach into those global cities that have the hubris to think they are finished, and start leading them rather than just learning from them.

In place of that world’s history and bigness and wealth, we have now laid out before us such unprecedented creative freedom. It is our collective responsibility to continually and aggressively exploit that freedom, and lead the world into its own future. For the first time in my life, though, I do not know what that future ought to look like. This — this not knowing — this is all I might ever have hoped for. In the absence of knowledge, I have found hope.

THE END

I will walk off this stage empty. An hour ago it meant everything to be able to speak to you. Now it is spent, it feels like nothing. And all I want is to work again. I guess I have given you everything I have. I hope it is worth something to you.

Tonight you will walk back out into our city. Believe with conviction that your most exquisite present will be created solely from the depths of your hunger for the future. The urgency of this potential ought to make you burn with lustful impatience. This is a city and a country and a culture in the thick of radical transformation. I believe without reservation that the scale and speed and appetites of our time make this best place on Earth from which to tear an entire culture to pieces, and rebuild it. All I fear now is that I do not have enough adrenaline or blood or luck to play my part.

I used to fear that we might not be good enough. I used to fear that we might never have the opportunity to find out. I do not fear this anymore.The world outside these doors has changed. We have changed. The exquisite future is real. It is possible.

It exists. It is ours. Do not rest.