Nov 24, 2022 Art

There are two ways to think about the Pacific Ocean as it pertains to painters in Aotearoa. It either informs the artist’s life and work in innate ways, or the artist thinks nothing of it. For many Māori and Pacific artists, Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa is a body and an ancestor and a connective passage, alive and mythic at the same time. In the European tradition, artists and thinkers have tended to accord landscape a ‘reality’ and disavow the sea as beautiful, an abstraction, tracing a distinction between the symbolic materiality of earth and the mutable and unsettled ocean. It’s a tension that has both animated and been examined in Western arts and science for centuries. This conception diminishes our read of the Pacific Ocean, despite its sublime power — an irony given ‘Pacific’ derives from the Latin pace, later ‘peace’, when the epithet Mar Pacifico or ‘peaceful sea’ was bestowed upon the blue chasm by a Portuguese explorer in the 15th century.

In On Beauty and Being Just, theorist Elaine Scarry proposes a throughline between beauty and justice, arguing that beauty is a categorical principle of social equality. Beauty has, in Western contexts, been demoted within political life as insubstantial, disparaged as a seductive distraction from the collective possibility of egalitarianism. By contrast, Scarry contends that beauty can produce a profound aesthetic occasion that destabilises our individual condition, thereby advancing an ethical encounter of the collective and moving toward questions of justice. Beauty is, then, both leveller and utility, from which equality can arise. It is, Scarry proposes, a “radical decentering”.

The slim volume surveys arguments on beauty from classical through to mid-20th-century philosophers, including Simone Weil, who maintains that beauty determines we “give up our imaginary position as the centre”, and Iris Murdoch, who describes it as “unselfing”. Considering Kant’s aesthetic categories (an analysis that divides the domain of beauty between the beautiful and the sublime), Scarry writes: “The sublime is male and the beautiful is female, the sublime resides in mountains, Milton’s hell, and tall oaks in a sacred grove; the beautiful resides in Elysian meadows and flowers. The sublime is night, the beautiful day… the sublime moves, beauty charms.” The sublime is, she continues, an “aesthetic of power”.

As with desire, beauty is mimetic; it elicits action by what it confers upon us; it incites imitation and reproduces within us; finds expression in sensorial occasions, a “criss-crossing of the senses”, producing works of art, literature, poetry, music. An encounter with beauty can obliterate the self.

The ocean and beauty are both qualities that viewers often reach for — for better or worse — when they encounter the paintings of Anoushka Akel. Better, because both are identifiably categorical and aesthetic arrangements to which Akel’s work relates. Worse, because beauty is contested territory. In contemplating art, ‘beauty’ is a readily seized descriptor that risks lifeless thinking — that a painting be described as ‘beautiful’ is so unconsidered an adjective it is often rendered moot.

Anoushka Akel is a Tāmaki Makaurau artist who was born in 1977 and works primarily across painting and printmaking. Of Lebanese and British/Pākehā descent, Akel has an orientation and disposition that distinguish her from her peers. She seems to possess that rare and particular quality of anachronism held by the wise; displaced, somewhat alone, shadowing herself, somehow both born too soon and too late. Her career has tracked not an obdurately ambitious path but one guided by intuition and discernment.

In Wet Contact, an exhibition from earlier this year at Michael Lett, Akel presented abstract, oceanic paintings; surface fields of muted teal, blue, violet and grey alit in moments with bitter orange and fiery coral. Unframed canvases were marked with horizontal forms and line work that suggested borderlands of mind and body and the turbulent rhythms and heavy depths of the ocean; of fins, cresting waves, currents, eels , teeth, rising masses, estranged limbs and anatomy. In the paintings could be found, as in Akel herself, the subterranean, the psychologically penetrating, the beguiling, the uncertain; they were the surfacing of a mercurial unconscious. Wet Contact was shown in the airless basement lair of the gallery. It was a bookish show, Akel says. While making the work, she read with an intense degree of close study, which she says felt like “going under”.

The alterity of the body, the mind and the self — specifically the self in relation to the first two — occupies Akel. There is an evasive, distancing quality to her work — at times a menacing and sublimated anger. In some measure, the concentrated layers of her paintings appear to communicate those old tensions of the sublime and the beautiful. As with Akel’s thematic interests in power, love and embodied knowledge, her explorations in the fields of cognitive psychology, psychoanalysis, poetry, literature and science, they are not diametrical categories but adjacent; affiliated in mysterious negation.

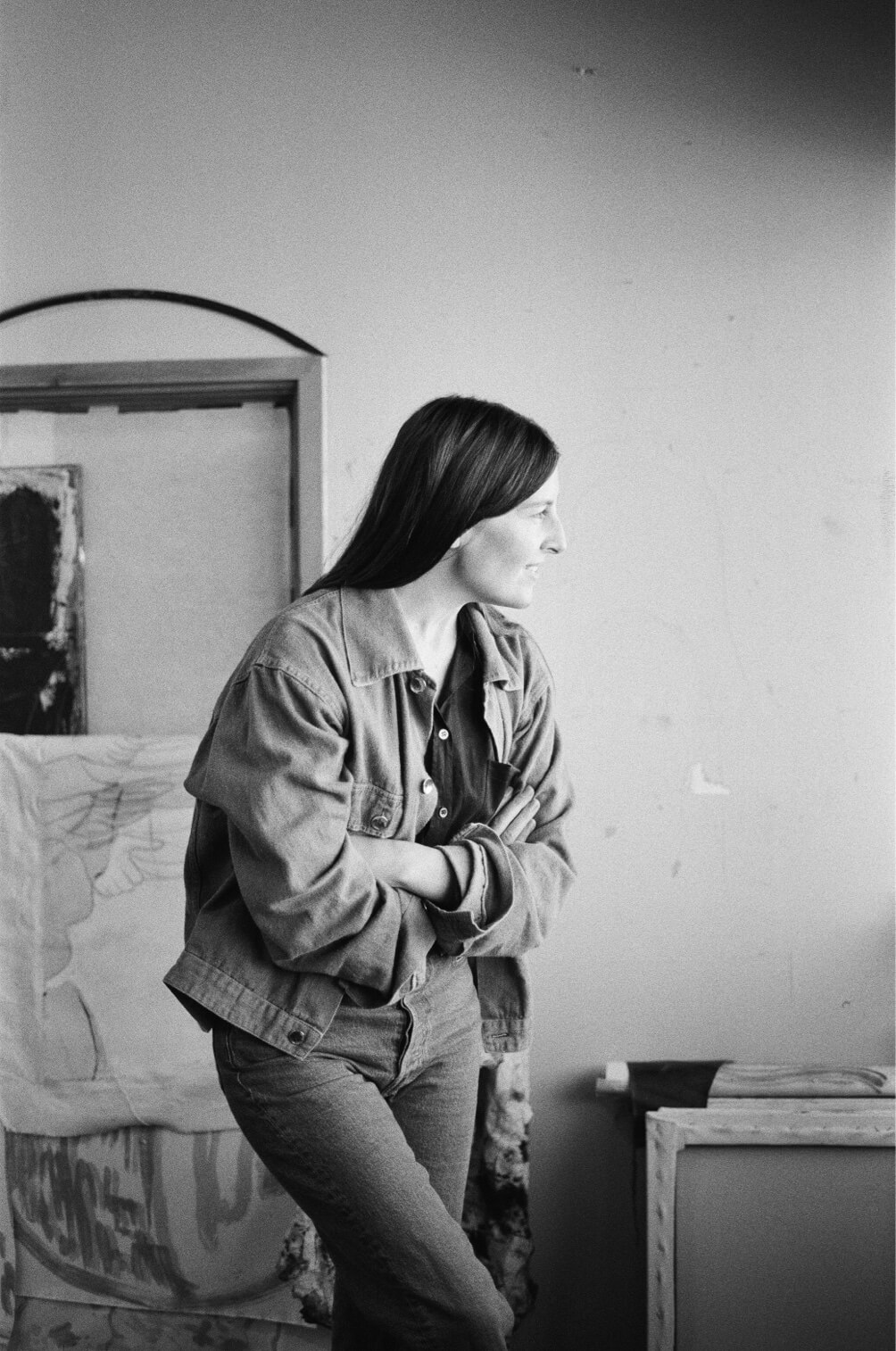

As an artist who has exhibited widely, represented by one of the country’s most esteemed galleries, Akel has arrived at an interesting moment in her career. We meet over several afternoons, turning to evenings of roaming conversation at her studio, a light airy space inside Samoa House, overlooking Karangahape Rd. The walls are studded with paintings and studies, drawings and quotes scrawled at slant on paper. Books and vestiges of ideas carpet the floor. The quiet of her studio is punctuated by rolling sirens and the hiss of bus brakes below. Broad windows offer a wide view over the kinetic street toward Maungawhau, rising above grey rooftops in the distance.

Birdlike and slight, Akel carries both an elegance and a teenage slouch; she has long silken hair and wears oversized 90s sweaters. With disarming intellect, she talks discursively but with measured composure — sharing with startling generosity, then withholding within the same sentence, constantly deliberating and adjudicating or negating her own statements and thoughts. She is contemplative and analytical, philosophical and funny; equally Anoushka Akel tender and sharp; a study in contrasts. Together we discuss her recently lauded show; the ruptures of Covid and of motherhood; her confidants and peers; her commitment to her intellectual and literary preoccupation; and her more recent interest in epigenetics, ancestry and lineage.

Wet Physics, oil on canvas at Michael Lett gallery, image supplied

Akel’s relationship to literature animates not only her work but the relationships formed around her practice. She has been having an unfolding conversation with a psychoanalyst friend over recent months, and the transcript is a penetrating and probing dialogue between two friends intellectually invested in human mechanics, cognitive processes and the expressions of each other’s inner lives and histories. Writers were central to her practice for Wet Contact, and she drew in particular on poets Adrienne Rich, Alice Oswald and Lisa Samuels — though she was “wary of illustrating somebody’s writing”. Particularly affected by Samuels’ essay “Membranism, Wet Gaps, Archipelago Poetics”, from which her title Wet Contact stems, Akel enlisted the poet and academic to write an accompanying text for the show. Lines from Adrienne Rich’s epic Diving into the Wreck were another key point of departure: The sea is another story / the sea is not a question of power / I have to learn alone / to turn my body without force… I came to explore the wreck. / The words are purposes. / The words are maps. / The thing I came for: / the wreck and not the story of the wreck / the thing itself and not the myth…

The paintings in the show were made during lockdown, with no sense of an exhibition on the horizon. Akel emphasises that the peculiar quality of time during that period shaped the work. Frustrated by being unable to work in her studio and by the closure of Mossman, the gallery that had until then represented her in Wellington, she made a decision to orient her life by the axiomatic “I here now”, or “we here now”. Akel reads me a quote by fellow New Zealand artist Vivian Lynn:

I decided that many years ago my life and work were about I here now. Wherever I was in the world, this was my anchor. Being grounded in I here now has been essential, I think, in stopping sliding into generalisation, nationalism, universalisms, maybe romanticism, and so on.

For Akel, this means: “I have to bring my life and practice closer together.” She describes seeing a vision of herself in her car, saying, “Being a parent means there’s a lot of movement and there was a moment where I thought I was going to lose the studio… I thought my car could be the studio, drive it to the park… It was always, ‘How do I make this work?’ Sometimes it’s a survival game, honestly.”

Did she feel unmoored, then?

“I did and I didn’t. It was the first time I felt, ‘Forget the audience!’ I don’t need an audience. I felt this in response to an interview I’d been doing for a book, and I felt I was taking in all this pressure and all these demands and had this amazing moment where I pushed it all off me and out into the world.”

There is a melancholy to Akel’s paintings that stands in contrast to Akel herself, who is not. Akel is at times vexed by perceptions of her work. She’s aware that her surfaces are beguiling, that her use of symmetry and a largely monochromatic palette support this reading, but she struggles with the disconnect between the work that goes on in her studio and its reception. “That there’s not more complexity of emotion, of reading, it makes me feel like I’m missing something… When people only use the word ‘beautiful’ at me — and I don’t mean to sound critical, because I know that I have trouble articulating my painting — I’m always surprised. I worry that I’m not actually communicating anything. If that’s the only word that’s going to be attributed to my lifetime of painting, then I should probably just cut out the huge amount of questioning going on and make life easier.”

Unsurprisingly but regrettably, an artist’s persona also factors into the way their work is perceived. And Akel is personally beautiful, technically and objectively. Perhaps it follows that artists tend to resemble their work — beauty begets beauty, after all. Someone once told Akel that she ought to make a “really ugly painting if you’re frustrated by this idea of beauty”. But, she says, “embarking on something purely about aesthetics is not interesting to me”.

In a recently published book, The Dialogics of Contemporary Art: Painting Politics, edited by art historian Suzanne Hudson, to which Akel contributed artwork and a dialogue, she contends with the sense of belonging in her early years as an artist: “For many years I thought that I needed to earn the right to be an artist, that I needed permission. This meant spending too much time with art histories that were unhelpful to me as a then-young woman.”

Akel did, however, always know she wanted to be an artist. Growing up in Tāmaki Makaurau within a diasporic and complex family dynamic, Akel took refuge in art. Her mother is British and her father a Lebanese New Zealander, born in Whakatāne. (His father was born in Beirut and migrated to Wellington as a child in 1922, becoming a paediatrician.) When Akel was seven months old her parents divorced, and her father moved to California, then later to Prague, where he now lives teaching law and making films. Akel has a journalist brother in New Zealand and a half-brother in New York City. She herself, here in Tāmaki, is married to a sound artist/designer and together they have a young daughter.

Anoushka Akel

Akel was not acculturated within Lebanese culture and it is not necessarily an identity she claims. “There is a distinction between calling me a Lebanese artist and an artist with Lebanese (and British/Pākehā) heritage. The former implies that your cultural identity is very much front and centre of your practice, moving and shaping it more than other influences. In my case, I can’t and wouldn’t claim that right now.

“The lost or at least the disconnected part of my family history — loss as a result of pressure created by political conflict, by racist, colonial immigration policies and by historical family grievances — is one of several lines feeding into the practice. It sits contiguous with my interest in the transformation of materials, in physics, philosophy, human and non-human animal behaviour, and, of course, art history.”

Discussing family elicits some discomfort in Akel. Trying to marshal her life into a coherent order only reminds her of what can’t be quantified. To converse with Akel is to listen to the silences and the pauses; to listen not for what’s said; and to be reminded that biography is a conceit troubled by its own making that resists its own intentions to name and claim. In contempt of this, some facts: Akel was a precocious student who, during high school, took drawing classes with the late feminist figure Allie Eagle — the fi rst of several formative pedagogical relationships. Her early life was chaotic but stimulating; her father’s leftist politics and legal background invited her to challenge her thoughts. Drawing was a quiet space, which she sought for stillness.

Raised by a solo, full-time-working mother for a significant portion of her childhood, Akel found feminist politics at an early age. She remembers being changed in her classes with Eagle, convinced by her presence and politics. Akel went to Elam, where she felt she didn’t have much to say, then lived abroad for some years, during which time she rarely painted but made short fi lm sketches on her phone, and worked as an artist’s assistant in London. She went to Venice, to New York. Those years were about looking. Akel also worked at the Melbourne Museum on a show which surveyed three centuries of Italian art — a panoramic absorption in art history that Akel describes as “the opportunity of a lifetime”. Over the eight fallow years between her undergraduate degree and her master’s, Akel says, she inhabited the world with no determined objective beyond the osmosis of living. Artists (and writers) like to pretend that they emerge fully formed.

Akel, aged 31, initially returned to Aotearoa to undertake a master’s degree in documentary film with Annie Goldson at the University of Auckland. In class during the first week, listening to her cohort discuss the logistics and practicalities of filmmaking, she was hit with an epiphany: she was a “total fake”. Akel made two days’ worth of a documentary about the Elam mansions being razed and within a week enrolled in the master’s programme there instead. She began to develop a sense of conviction about being an artist. Peter Robinson was her supervisor, a great influence and mentor, and her cohort was fortifying: she marks out Luke Willis Thompson and Lauren Winstone as particularly close and intellectually challenging peers. Akel joined a small and serious group who privileged robust conversation, and over these two master’s years — as well as into the intermittent present — she was employed at the school to teach.

Two years after graduating, Akel was paired with artist Kim Pieters in a 2012 show at Artspace, Hopscotch, curated by the gallery’s Italian-born director Caterina Riva. It was a critical moment for Akel. The offer of the show surprised Akel, but from there, gallerists circled. She joined Sue Crockford Gallery, which closed six months later, leaving her in an indeterminate position. To align with a dealer is to foreclose other options — a tricky position for artists to navigate, especially younger ones. The social complexities and politics of the art world are notoriously fraught. Without representation for several years, Akel continued to make work, undertook a residency, and was included in several group shows including Necessary Distraction, a 2015–16 painting survey show curated by Natasha Conland at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

From there, she joined Hamish McKay Gallery in Wellington; had a daughter; won a substantial prize which allowed her to paint full time; and joined the gallery Hopkinson Mossman, latterly Mossman, where in 2019 she exhibited the acclaimed show Learners. In 2020, Mossman closed. That same year, Akel showed in Tokyo, and in March 2021, she was picked up by Michael Lett Gallery in Tāmaki. Michael Lett’s co-owner and co-director, Andrew Thomas, had followed Akel’s work through all these twists and turns. Of the 2012 Artspace show, he remembers that “the formal gestures in those paintings really resonated with me”. He also connected with Akel through hearing her speak about her work, which he found “delicate and precarious, yet confi dent and resolved both formally and conceptually… The material processes she was using felt very much her own.” The properties of water expressed in the paintings of Wet Contact resonated with Thomas, as they did with gallery associate and academic Victoria Wynne-Jones, who also has a long connection with and interest in Akel’s work.

Wynne-Jones describes Akel’s painting practice as singular; her paintings as objects that “work through and intuit entities and felt states that verbal language cannot keep pace with”. As with Thomas, she was initially drawn to the work through its formal interventions and colour palette, the “bruisey blues and violets”. Following Akel’s career from a distance, hoping an opportunity might arise to more formally engage with the work, Wynne-Jones was introduced to her during a 2019 series of artist-initiated group critiques that occurred in studios across the city. Akel, she remembers, possessed a “charming yet interrogative manner that caught my attention… she is an artist that operates with a tremendous amount of sensitivity.”

Wynne-Jones recalls noting a shift in Akel’s work in a Hopkinson Mossman show where, she says, the work became “more fleshy and bodily”, and where, she continues, their mutual concerns converged. On reflection, she describes her work as “not really of or about bodies, but more dealing with the forces that bodies are prey to or enact: rubbing, touching, pressing, perceiving, reflecting, contemplating, adoring, insinuating, dominating… the ways bodies affect and are, in turn, affected.” That supreme matriarchal art figure, Louise Bourgeois, maintained that you can accept your life or you cannot. If you cannot, you become a sculptor. Bourgeois is, like Akel, an artist concerned with what haunts her margins.

Examiner, oil on canvas, 600x450mm, image supplied

“You can have such large experiences with art,” Akel says. While history’s shadow travels through the self and finds its residue in memory, Akel restates her concern with inhabiting the present, the now. It is something to do with an increase in confidence — while, she goes back on herself, “never wanting to be a senior on a subject”. On the phone one evening, Akel mentions that she has, during these past weeks of talking, become less afraid. As an artist you travel in and out of your interests, she says, and particular to this period of her life is an embrace of aspects of her heritage that were previously more marginal. She has proceeded into her own history with renewed interest, connecting with relatives and researching her diasporic heritage. There is perhaps something in the act of disclosure that loosens personal narratives; to speak aloud and attempt to cohere your life might precipitate a reassessment of thoughts and beliefs. What you resist might catalyse the unexpected and expand your sense of what is known and possible. This is operative in Akel — and it is what she hopes her paintings might do.

An artist does not ever arrive. A work of art, or a body of work, might try to express the totality of an artist’s idea and intention but art is, ultimately, a pursuit that resides in the abiding in-between. To answer the call of fidelity to feeling is a costly ask. To meet and get to know an artist like Akel, who shapes her life inside and around her practice so that the two might fuse, is to realise that there is no other answer, no other life.

–