Jan 9, 2016 Books

One of the most influential writers of his generation, Bill Manhire shares his son Toby’s love of language and quick, inquiring mind – if not, as Sarah Lang discovers, his passion for cricket.

This article first appeared in the December 2015 issue of North & South. Main photo by Ken Downie.

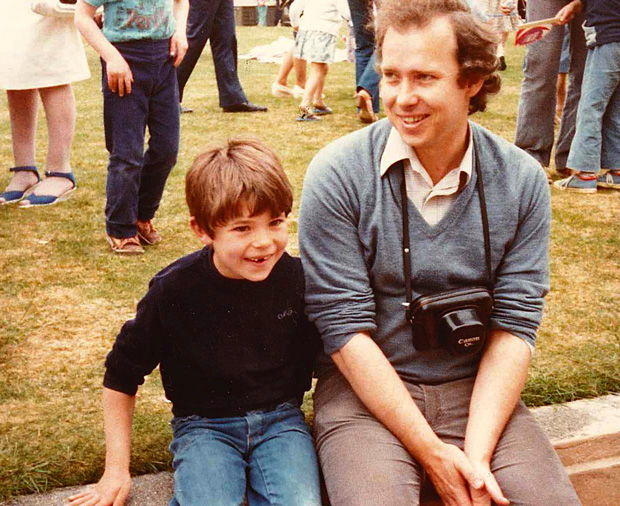

In his central Wellington apartment, Bill Manhire is leafing through some family photos near a wall of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and the “Katherine Mansfield Birthplace” sign he found on a roadside. The son of a South Island publican has never been a garrulous type, but warms up a little talking about his son, Toby, now a journalist in Auckland. “He was a gorgeous boy,” he says.

Bill and his wife, Marion McLeod, a longtime writer and subeditor for the Listener, brought up Toby and older sister Vanessa in Kelburn, where Bill lectured in English at Victoria University. In 1975, Bill founded Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters (IIML), the creative-writing programme that would have a major influence on New Zealand literature.

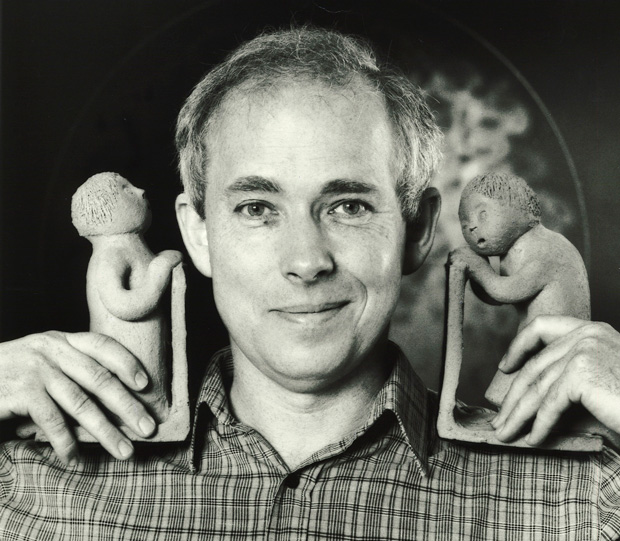

Meanwhile, he wrote a lot of poetry and some short fiction, edited many New Zealand poetry anthologies, and received numerous fellowships, awards and honours, including being named New Zealand’s inaugural poet laureate. He’s also collaborated on albums of poetry set to music with composer/jazz pianist Norman Meehan, on science and art projects with the late Sir Paul Callaghan, and on books with the late Ralph Hotere (the artist, a close friend of Bill’s, was Toby’s godfather). In 2013, Bill left IIML to write fulltime.

Both Toby and Vanessa share their parents’ love of words and stories. An editor for Otago University Press, Vanessa also works remotely for the Cambridge University Press. “She is the proper scholar in the family,” says Manhire.

While living in London for 12 years, Toby was editor of the Guardian newspaper’s comment (opinion) section, before returning to New Zealand with his family in 2011. He lives in Pt Chevalier with his wife, Emily – head of development for film company Libertine Pictures – and their children Alexander, five, and Tessa, three.

As a freelancer, Toby contributes New Zealand-based features to the Guardian, writes weekly columns for the NZ Herald and Radio New Zealand online, and is politics editor for The Spinoff website. He’s also edited two books: WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy and The Arab Spring: Rebellion, Revolution and A New World Order, a collection of journalism from the Guardian.

In November, Toby stopped by the capital for LitCrawl, to revive the famed pub quiz he and a mate used to run in Pt Chev. At the same time, his father proved he’s still no slouch on the work front.

On November 12, The Stories of Bill Manhire (Victoria University Press, $40) – a sublime collection of short stories both old and new – was released at Unity Books. The following evening, Bill performed in a concert for the Wellington launch of the album Small Holes in the Silence by Meehan (piano), Hannah Griffin (voice) and Hayden Chisholm (saxophone), who created new jazz music from old poems by the likes of Tuwhare and Baxter, and also from three new Bill Manhire poems.

Bill Manhire, 68

“I was in the delivery room when Toby was born. That was unusual then for fathers, but our GP let me go in if I promised not to tell any other patients. Toby arrived pretty quickly, and he’s still a speedy fellow. As a toddler, he was quite reckless at the playground and he’s never really lost that quality – not recklessness, exactly, but resourcefulness and courage. Much more than I have.

Toby was cooking family meals at seven. We always had our meals together – and a lot happens at mealtimes. You find out stuff the kids are doing, you talk about the evils of Robert Muldoon. We didn’t have a dishwasher, so I’d usually wash and one of the children would dry. So, oddly, doing the dishes was a bonding time.

Toby always loved cricket. When he was about 12, the family were reading at our Waikanae bach when Toby looked at us and said, ‘How the hell did I end up in this family? All you do is sit around reading books!’ He picked up his cricket bat and stormed out. We did practise a bit of cricket together, and I coached his cricket team one year, which can’t have been fun for the players. I once wanted to be a stage magician so I had a magic kit, and was a very bad amateur magician at the kids’ parties. I’d make cigarettes disappear up my nose and produce eggs from trouser bottoms.

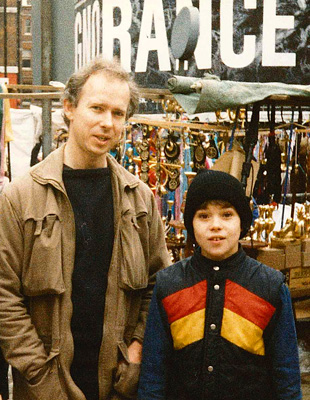

When we lived in London for a year, we took Toby and Vanessa to a small demonstration by expat New Zealanders during the 1981 Springbok tour. At five, Toby might have understood why we went, and he did understand that’s why we wouldn’t let him play rugby. He says the world has lost a great rugby player because we made him play soccer. I also remember taking the kids to the public gallery in Parliament when the Homosexual Law Reform Act was passed in 1986. We lived in London again in 1987 and, at 11, Toby was taking the Underground to explore London, far more than we knew then. He was always a very independent kid.

At high school, Toby was a drummer in a band. My wife and I would go to the bach and leave the band to destroy the neighbours’ lives. There were obviously parties – sort of failed attempts to tidy up the house. Toby was also drummer in the Guardian’s in-house band.

We encouraged him to do first-year law, but it wasn’t for him. Obviously we wanted him to do what made him happy. Toby wanted to be a playwright and wrote a couple of really good plays. Now, as a journalist, he’s an interesting person to talk to and ask about what’s going on in the world. We have quite similar takes on things, and he’s interested in a world that overlaps with my world [of writing]. We’re pleased he’s done well; it was obviously nice to have a son running the Guardian’s comment pages.

But the thing I’m proudest of was his decision that, if he and Emily had kids, he’d do half the childcare. And he’s totally done that, while working a bit more than fulltime. I admire him for that – men of my generation talked about it, but didn’t tend to do it.

I was terrifically pleased Toby came home [to New Zealand]. He and Emily had wonderful jobs, but they wanted to be back here with time for their family. With Toby in Auckland and Vanessa and her family in Dunedin, we have to get off our bums and visit, and they zoom down here occasionally. And we all go to the bach. It’s nice to see Toby’s kids running around the garden and beach that he ran around on. And there’s nothing better than having a small child on your knee impatiently turning the pages of a story.

I Skype the little kids and talk to Toby quite a lot. He’s a very good father, better than I was. He has his bossy moments and a little of my cynicism, but he’s a definite evolutionary improvement on me. I’m a rather cautious, inhibited person. Toby’s got more grunt, oomph and energy. He can be pretty cheeky, mischievous and entertaining – and still be a serious person with a strong moral compass. I really like that mix.”

Toby Manhire, 40

“Dad’s always been laconic and relatively quiet – not one for demonstrative behaviour. But he’s also very quick and funny. There were plenty of laughs in our house, and he’d always do the magic at our birthday parties.

He had a good repertoire of tricks: eggs in secret compartments, steel hoops mysteriously intertwining, and I seem to remember rabbits coming out of hats. It was proper stuff that had an audience of five-, six- and seven-year-olds genuinely gasping with astonishment. I remember feeling quite pleased my dad was able to pull that off. He was probably training himself up for months beforehand.

Until my friends started coming over, I didn’t realise that having the walls paved with books – almost literally – was an incredible privilege. Our parents read chapter books to us in the evenings: Margaret Mahy, Maurice Gee. If one of us wasn’t sure quite what a word meant, Mum would leap up from the table and get the Oxford English Dictionary and look it up. It used to really annoy me, but now I do the same thing with my kids.

We also made wild and elaborate books by hand with our neighbours, the Grays, with stories about characters based on our family’s different personalities. Dad typed the words on his old typewriter. Our friends’ dad, John Gray – an architect – drew the pictures. One book was called Circus in the South, set at the South Pole. A bunch of Super-8 films feature Dad as a terrifying “Lurky Monster”, complete with those Groucho Marx-style glasses and moustache things, chasing the family around. I was about three and wobbling about wearing paisley underpants and my sister’s fairy dress. I’ve always been close to Vanessa, though for a while there I was probably a pretty beastly younger brother, and have certainly taken her for granted at times.

I have moments of déjà vu and nostalgia when I see my childhood relationship with my parents reflected in my relationship with my children. Alexander just sits down and writes about what he did on his holiday, and I see his grandparents delighting in his writing: excited and supportive but not at all didactic. I feel my parents were the same way with me. When I was 10, I had a poem called My Street published in a Sunday newspaper, about the things I saw and heard around our bach. I think my parents were quietly pleased.

I have moments of déjà vu and nostalgia when I see my childhood relationship with my parents reflected in my relationship with my children. Alexander just sits down and writes about what he did on his holiday, and I see his grandparents delighting in his writing: excited and supportive but not at all didactic. I feel my parents were the same way with me. When I was 10, I had a poem called My Street published in a Sunday newspaper, about the things I saw and heard around our bach. I think my parents were quietly pleased.

My family were always reading. I remember hanging around the bach with an Excalibur cricket bat, desperately trying to persuade them to come and play with me. Clearly my family are responsible for my failure to progress as an international cricketer. But Dad did spend many hours giving me slip catches.

I studied politics, theatre and film at Victoria, living at home the first year then flatting, and one year I edited the student paper [Salient]. Dad and I had coffee every week or so on campus. I don’t think I ever leaned heavily on him, but occasionally I’d ask for bits of advice, which I probably took for granted. I’m sort of embarrassed to say this, but at university, with quite a rare surname, I sometimes felt weighed down by expectations of me as Bill’s son, or that my achievements were sort of nepotistic, but that washed away when I went overseas.

As a kid, we went to live in London twice, for about a year when I was five, then again when I was 11. We were living in Bloomsbury, in a neighbourhood square of flats for overseas academics. Those were fantastic times as a family. So London was always alluring to me and I moved there as a 20-something. I got my foot in the door at the Guardian and refused to leave. We came back after Alexander was born. It was the draw of family and wanting your kids to run around barefoot at the beach, like you did.

We all meet up at the bach for holidays. Mum and Dad quite often stay with me in Auckland, and I’ll normally stay with them in Wellington. We see them most school holidays, and we’ll chat on the phone two or three times a week. Often I’ll put one of the kids on the phone to Nana and Billo, as they call Dad, and they’ll talk for 10 minutes, then pass the phone to me. When we’re chatting, I’ll quite often talk to Dad about my [Herald] column, which tends to be political. Politically, we’re roughly on the same page, though I’m not sure what page that is.

Dad and I follow each other on Twitter. When he and Mum were in London recently, and I was down in Wellington using their car, he tweeted something cryptic about a speeding ticket. I felt that tweet was possibly an indirect way of sending me a message, not that I’m making any admissions. But he never hit me up for the money.

Dad’s got quite a well-developed bullshit detector. I’ve probably picked up a certain amount of scepticism from him, by observation, not tutorage. But he’s also a humble and generous bloke who’s always had time for people looking for advice and help. I’ve been very lucky to have a father with so much knowledge – and [industry] gossip. He’s quite a good gossip, Dad. You wouldn’t think so because he’s quite inscrutable.

I’ve always been impressed by who Dad is, what he’s done, what’s he doing. His musical collaborations are just fabulous, and the new book’s fantastic. I feel totally proud of him. I really do.”