Apr 21, 2015 Books

A man answers his door early one morning to discover an old friend standing there. The friend has a story to tell.

A young student befriends a brilliant outsider at university and through him is drawn into a world of complexity and glittering promise beyond his imagining.

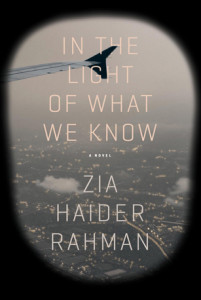

They’re storytelling archetypes, the pair of them, and for his first outing as a novelist, Zia Haider Rahman has used not one but both. In the Light of What We Know is like that: full to bursting with ideas and bound together with a precocious literary skill. If you sometimes think, does any novel need this much in it, that’s not to take away from the enormous pleasure to be got from exploring all that content.

It’s 2008, London, the year of the Global Financial Crisis. US-led troops are deeply mired in Afghanistan and our two protagonists — an English Bangladeshi called Zafar and a Pakistani Englishman (the unnamed narrator) — have both have reached a state of personal ruin, though in very different ways. How did they get there? For the narrator this is a coming-of-age story, never mind that he is already a middle-aged man.

The book has been praised as a great “21st-century novel”, which means not just that it exists in the aftermath of 9/11, but that it does this from outside the perspective of middle-class white Britons and Americans.

There are lessons in geopolitics. The Bangladesh war of secession from West Pakistan in 1971 left “three million dead, hundreds of thousands of women raped, an entire generation of professionals… exterminated”. In Kabul, when the UN and the NCOs arrived, locals who spoke English well were lured from their jobs as teachers and business managers to the better-paid life of drivers and other Western servants. The individuals were better off but the country became less productive. Meanwhile, the Taliban sold their homes to Western diplomats: real-estate values went through the roof and the Taliban made money.

There’s anger running through this story, and you don’t want to look away. Yet if Rahman seeks to confound any simple understanding we might have of these countries, that’s far from his only goal. He’s also determined to appropriate English literature. On every page the book channels, comments on and pays homage to the great novels and other works that have gone before — often quite explicitly.

There’s fun in this: oh, you think, we’re in Graham Greene territory, and now it’s Coleridge, and just in case you were in any doubt up pops someone reading The Quiet American or dealing with an albatross strung round their neck. So to speak. The book is openly informed by Somerset Maugham, John le Carré, George Eliot, and non-English writers too, especially V.S. Naipaul and Tolstoy.

Most of all, though, it’s Evelyn Waugh and F. Scott Fitzgerald: Brideshead Revisited and The Great Gatsby are the two great pillars off which this novel swings, and Sebastian Flyte and Nick Carraway haunt its pages.

Literature and politics, and that’s not all. Gödel’s mathematics — the Theory of Incompleteness — provides another framework (don’t worry, it’s explained), and there is also much to do with philosophy, particle physics, carpentry and other building trades, history, the scientific method, the English language (got the hang of anaptyxic epenthetics?), psychology, law, accountancy… Zafar and the narrator are Oxford educated, you see, and what good’s a brilliant education if you don’t know stuff?

And yet, of course, that’s their problem. They don’t know stuff. Both men are largely ignorant of their wives, struggle to understand the forces acting on the world around them, know less about their own national histories than they would like.

Rahman’s imagery can be vivid: “her wrecked teeth, like a mouthful of broken cigarettes”. He has Zafar quote Virginia Woolf (“Of course love is the only thing that matters to us — just think of all the delusions we maintain in order to preserve it”) and then transcribes in a narrator’s footnote the Woolf original, which is not as elegantly phrased as his own. He is nothing if not confident.

And this: “He left her with her circle of admiring men… men ever gravitating towards her, as ripe apples to the soft earth.” Metaphorically rich, with a charming nod to Newtonian science, and freighted politically too. They’re in a UN bar in Kabul, where “the music was loud… a volume to muffle the clamour of sexual gambits unbuckling over the scene… this is the freedom for which war is waged.”

Best of all, Rahman knows how to construct a tale, and naturally enough in such a self-aware novel, he tells us with a metaphor: “The exquisite handling of information, its measured holding and release, like an inch on the reins of a dressage horse.” The phrase is used in relation to English aristocrats, but it’s true for everyone else in the story too, and for the story itself.

There is knowledge of the world: those who need to break free of the past and have the means to do so “will not escape the requirement of violence”. And there are delicious insights. “You’re not a trusting fellow,” a spymaster tells Zafar, “but you very much want to trust and in the right conditions you will do so.” When would that be? “When you believe you are taking principled action.”

And, finally, when Zafar has told his story and disappeared again: “What I will not hear now is that beat of one’s own heart audible only in the presence of human affection. His absence will be felt.” Nobody does measured heartbreak half as well as the English. Wherever they come from.

The book ends with a photograph of two friends, and the narrator’s reassurance that friendship, if it’s profound enough, will sustain us. Yet his friendship with Zafar has fallen apart, and as this book is a homage to the history of the novel, we can assume it has reached the stage of postmodernism. Everyone and everything — photos included — bears unreliable witness.

At one point, as if to explain his enormous canvas, Rahman quotes Italo Calvino: “Literature remains alive only if we set ourselves immeasurable goals, far beyond all hope of achievement.”

He also declares this: “Everything new is on the rim of our view, in the darkness, below the horizon, so that nothing new is visible but in the light of what we know.”

In the Light of What We Know interrogates that idea for all it’s worth. It’s a splendid read.