Jan 19, 2024 Books

You’ve probably been stopped in your tracks by Rewi Thompson’s work — on Wellington’s waterfront, or in a residential street in Kohimarama, or at the Ōtara Town Centre — but never knew the genius behind the design. Fittingly, Rewi: Āta haere, kia tere by Jeremy Hansen and Jade Kake is a biography like no other. Thompson did not leave a great body of built or written work before his death in 2016 at the age of 63, yet he is widely regarded as a visionary designer by his clients, students and New Zealand’s architects. By interviewing 35 of these close associates, researching a large archive of the architect’s drawings and notebooks, and asking other authors for creative responses, Hansen and Kake present a fascinating account of Thompson’s unique design methods that were based on his deep understanding of people and the whenua.

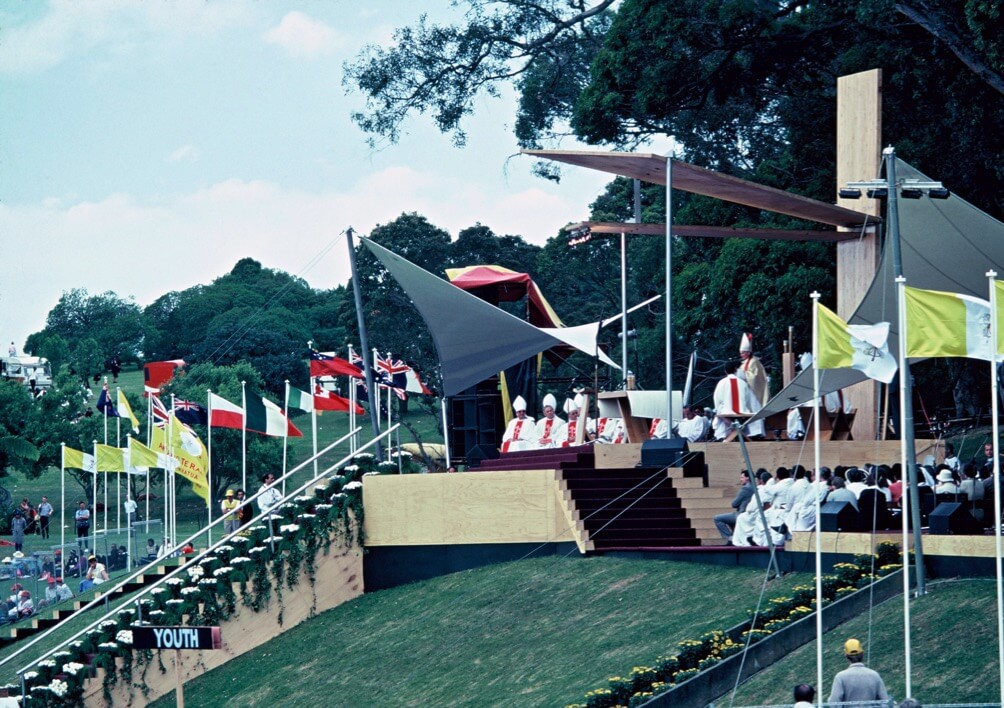

The authors also shed light on what happened to Thompson’s career after a rapid upward trajectory in the 1980s seemed to tail off in the 90s. Personal loss, the lasting effects of the 1987 stock-market crash and illness all but closed the door on that life journey, but this led to other opportunities in teaching and consulting that have left a lasting, positive impression on generations of architects and the lives of thousands of building users. The book lifts the lid on what happened to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa concept design pitch completed by Thompson in collaboration with Ian Athfield and internationally acclaimed architect Frank Gehry, which was, controversially, not shortlisted for consideration. It sensitively considers Thompson’s relationship with his Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Raukawa heritage and its bearing on his design philosophy and the definition of him as a Māori architect. Rewi is richly illustrated with Thompson’s drawings and photographs of houses, civic works, hospitals, exhibitions, educational, mental health and correctional facilities, and a canopy, altar and throne for Pope John Paul II’s 1986 visit to Auckland.

I was interviewed by Hansen and Kake for Rewi in my capacity as his friend and teaching colleague at the University of Auckland’s School of Architecture and Planning, which was recently renamed ‘Te Pare’ in honour of Thompson’s same-named educational philosophy. With the book now published, I had the opportunity to catch up with the authors to ask about their approach to the biography and what they learned about Thompson and Aotearoa New Zealand architecture through its writing.

Deidre Brown: Kia ora to both of you, and congratulations on the book. I really, really enjoyed it and felt that it captured who Rewi was, and also signalled very clearly, partly through the words and experiences of others, how important his contribution to architecture has been and his continuing legacy. And of course his drawings are just amazing.

As a first question: what led you to team up and choose to write about the career of Rewi Thompson?

Jeremy Hansen: I knew Rewi a bit when I was editing HOME magazine. I started there in 2005 and I kind of stalked Rewi because I really wanted to see and publish his house. I got in touch with him, and he very gently steered me away from the possibility of photographing the house because he said it wasn’t complete to a standard that he’d want to showcase. He steered me towards a home he’d designed in Newmarket instead, which you wrote about, Deidre. I kept encountering Rewi over the 11 years that I edited the magazine, and stayed in touch with him afterwards when he was working for Isthmus Group creating the Everyday Homes group of state-owned houses in Northcote shortly before his death in 2016.

After he died, the memory of him and his work stuck with me. Jade and I are friends and we happened to have a conversation about this one day. We both felt that a book on Rewi would be a great way to draw attention to his brilliant work and his contribution to architecture and architectural education, and we should try and do that.

Jade Kake: We got to the point where we were thinking, ‘Well, someone should do something, and maybe it should be us.’ We saw the enduring value in the work that Rewi had done and felt it was a story that needed to be told, so we just started the process. It was really critical to us that Lucy, Rewi’s daughter, agreed to the project happening. Thankfully she was really supportive. And I guess from a personal perspective, the reason I was keen to tell the story is because, although I didn’t know Rewi super-well personally, I’d undoubtedly been a beneficiary of his work and his influence. I felt that it would be nice to speak to that, to be able to tell the story of how graduates and architects like myself and of my generation have really been able to have these careers because of people like Rewi and others who’ve laid that foundation.

Jeremy: Although Rewi didn’t do heaps of high-profile built work, what he did build was very striking. When I would show friends images of Rewi’s house, for example, they would be taken aback. They were amazed by it, but they’d usually never heard of him. Buildings like Puukenga [the School of Māori Studies at Unitec] and Wellington’s City to Sea Bridge sat outside architectural orthodoxy in a way that was really intriguing. It all led to this desire to try and understand a bit more about Rewi’s motivations and creativity and share what we learned in the process.

City to Sea Bridge. Photo: Paul McCredie

Deidre: You’ve both hinted that Rewi didn’t leave behind a great body of work, but the book clearly shows he was a visionary. What do you think was Rewi’s greatest contribution in his lifetime, but also his enduring legacy?

Jade: It’s a big question, and it’s a tricky one to answer because he resisted being easily categorised as a Māori architect. I don’t want to narrow it into something like, ‘He made Māori architecture more of a thing in Aotearoa’, because that’s not how he would have thought about it. But he was really concerned with people and place and being of this place and thinking about things in a holistic way. Maybe his enduring contribution was to expand our minds about what architecture could and should be in this country, both in terms of outcome and process.

Deidre: The book’s structure is innovative — it includes interviews, often published verbatim, with 35 people. Some of them worked with Rewi in architecture, or in teaching, and you interviewed his daughter, Lucy, about living in the house he designed. To me as a reader, it almost felt like a 360° view of a person’s life, hearing all these voices. I’m really interested to know why you chose this approach instead of a singular biographical narrative.

Jade: Rewi was a multi-faceted person, like we all are. And I think there’s a lot of beauty in being able to show someone in a holistic way. I think it can be really limiting if you’re just focusing on the architect as a mythologised figure, and the diversity of perspectives helped us end up with a well-rounded picture of the person.

Jeremy: I think we were both instinctively resistant to this idea of a ‘definitive’ biography. Neither of us felt we could put ourselves in positions of being authorities on this man. We also talked about the books that we liked. One that kept coming up was Le Corbusier: Le Grand [by Jean-Louis Cohen and Tim Benton] which is almost like an archival document. As a reader you feel you have this privilege of leafing through the archives yourself, but somebody’s taken the care to guide you. I’ve also always enjoyed simple question-and-answer interviews: as a reader, you feel like you’re almost engaged in a conversation with the person speaking. Hopefully the visual nature of the book and its chatty text makes it feel accessible, so that non-architects and people who don’t know Rewi can dip in and out of it easily.

Deidre: Rewi was influential but his career was not straightforward, if I can use that as a term. Can you talk about some of the challenges and opportunities he faced?

Jeremy: Rewi graduated from architecture school in 1980 into this slew of hugely important projects: he designed a tent for the pope to sit in when he came to the Auckland Domain; he designed the canopies over the Ōtara Town Centre; he designed 20 state houses at Wiri for Housing New Zealand; he entered the Te Papa design competition with Ian Athfield and Frank Gehry; and he designed the City to Sea Bridge. Then things seemed to suddenly go quiet. I started the project expecting a single clear answer to why that was, but it was complicated. The 1987 financial crisis put a lot of architects out of work. Rewi’s wife Leona became really sick for quite a prolonged period, and he moved his office home to take care of her and Lucy. After Leona’s death, a lot of people told us that Rewi understandably seemed lost in a fog of grief. He seemed to find it more difficult to build a practice around himself to a scale that enabled him to compete for and take on larger projects. And he slipped into a collaborative mode of offering consultancy advice on other people’s projects rather than leading them. I feel a twinge of sadness as I talk about it, because I think about the buildings that Aotearoa could have had if Rewi’s trajectory had continued in the same way. But as we were doing the book, I realised that didn’t mean his influence waned. He became so important as a university teacher.

Ōtara Town Cenre. Photo by Sam Hartnett

Deidre: There are many different voices in the book — some of them are very influential in the profession of architecture, others are influential clients. We learn a great deal about these people. What did all of these discussions with practitioners, clients, whānau, students, colleagues in education tell you about New Zealand architecture during Rewi’s working life?

Jade: He saw so much change in his time practising architecture. The thing that I really reflected on is that he was starting out before the Māori renaissance. He grew up being an urbanised Māori in Te Whanganui-a-Tara and probably grappling with what that meant for his identity. It’s pretty typical of that generation where maybe they’ve been raised away from the hau kāinga — they do go home, but they maybe have a less strong connection to it than their parents.

It’s a really interesting period of change. The parents of children like Rewi are grounded in the culture, but are being told that for their children to succeed, they need to assimilate. It’s quite a thing to grapple with if you’re a visibly Māori person in an environment that’s still very racist and trying to make your way and prove you’re credible as an architect. I think that Rewi probably felt that people would try to dismiss him because he was Māori, rather than seeing that as a strength.

People would try to put him in the Māori architect box and he would be like, ‘No, I’m an architect. I don’t want to be a Māori architect.’ I could see why he said that at that time. But then society changed so much. We had the Māori renaissance, we had this big resurgence around the Land March, the Waitangi Tribunal, and reclaiming our language and the kura kaupapa movement. All of these socio-political things that were going on tangibly impacted New Zealand society, including architecture, and those things happened during Rewi’s lifetime. He had only just started out when that was happening, and then suddenly there were all these opportunities that didn’t exist before, and being Māori was valuable in a way that absolutely hadn’t been earlier.

Something that [Rewi’s friend and colleague] Mike Barns said is that Rewi came to his culture and identity in his own time and through his architecture. I thought that was a really astute observation. You see it in Rewi’s work and the way he writes about it, how he came to his own relationship with his Māoriness in his own time. As he matured as a practitioner, as an architect, that became a source of strength, that he was grounded and connected in his Māori identity.

Deidre: Rewi’s daughter Lucy donated a large collection of his drawings, models and sketchbooks to the University of Auckland Library, and you spent a lot of time analysing the collection. Everyone in the book agrees that he was a gifted designer. What did you learn in the archives about his design process and what made it special or unique?

Jeremy: The archives made us realise the book was doable. We were really worried about how we would illustrate a book that only had a limited number of built projects that were photographed. So when we discovered this incredibly rich resource, we knew it would hold the book together and enrich it visually. I think we learned from the archives that his design process was kind of relentless. He would draw and draw and draw: there were so many versions of projects in which he was considering and testing a really outlandish range of possible architectural responses.

Rewi’s daughter Lucy told us that he was always drawing at home, when they were out to dinner, on napkins, all that kind of thing. Ideas were just percolating the whole time. The other thing it gave us a sense of is how chaotic his mind sometimes was, because the archive was not an orderly place — the university archivists had begun the task of making it orderly, but you could tell that filing systems were not Rewi’s top priority, which was really endearing as well.

Jade: Rewi also left behind all of these notebooks and there’s just amazing stuff in there. Mussel fritter recipes and rugby tactics. There was also a drawing of a client he mustn’t have liked, some funny, angry comments around this man in a suit. It’s really hilarious.

Deidre: A thing that pops up through a lot of the interviews was that people commended him on his ability to turn an artistic concept into a building, which is probably the most difficult thing that an architect has to do.

Jade: He had this really pragmatic, practical background as a structural engineer as well as a wild, expansive imagination. I think that combination was a winner because he was able to think conceptually and have the concept drive his architecture all the way through to a practical built outcome.

Jeremy: His own house is a good example of this. One of the reasons it’s so revered is because it’s such a radical concept, but it’s also an expression of the possibilities and practicalities of built structure. As Rewi said repeatedly, it was primarily designed as a nurturing, functioning home for his whānau. The way it holds all those things together is really remarkable.

Papal Shelter

Deidre: Rewi worked with Sir Ian Athfield and Los Angeles-based Frank Gehry on an unsuccessful entry for the architect selection competition for the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa project back in the late 1980s. This was just a couple of years before Gehry won the commission to design the Guggenheim Bilbao. Can I ask: was the loss here not getting a big Gehry building or not getting a big Rewi building?

Jade: I think that combination could have been potent. All three of them are really interesting thinkers. Their proposal probably would’ve been quite a risky project, and maybe the appetite for risk just wasn’t there.

Jeremy: There’s something alluring about a lost project that wasn’t realised, especially when the authors of the project collectively offered so much potential. That story is a story of Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation at that time. There were absurd things in the brief like the need to preserve the V8 racetrack around Wellington’s waterfront. That was something that Rewi, Athfield and Gehry ignored. They proposed a museum that reclaimed land from the harbour and stretched out into it. Rewi and Ian Athfield were both fundamentally collaborative people, and it seems that Frank Gehry is of a similar bent. It’s really hard to let go of the possibilities that building might have delivered to us.

Deidre: You’ve touched on this already, but you quote Rewi as saying, and he wrote this himself, that he did not think of himself as a Māori architect. Do you think he was?

Jade: It depends what you mean by that. I think early on he was just trying to defend his position as an architect. But Rewi really was a Māori architect because of the way he was practising in a kaupapa Māori way, especially as he got into those later parts of his career. And I mean that in a positive sense, perhaps rather than the way it might’ve been thought of early in his career.

Jeremy: One of the many things that was fascinating about doing the book was watching that definition of what being a Māori architect means shifting and changing during Rewi’s lifetime, but also for him personally. In a way the book is a story of his journey, but also the journey of the professional and national culture around him.

Jade: I don’t know why this came to mind, but I had the idea of picking whakataukī for each of the chapters, and I think that was a nice way to capture the way Rewi thought. He was really concept-driven, philosophical and poetic as well as pragmatic in his approach; whakataukī are often very pragmatic or instructive or have some really specific meaning in there, but they’re also poetic, and make you think, and can have multiple meanings. I thought that was a nice thing to do, to connect with the way that I had grown to understand how Rewi thought.

Rewi: Āta haere, kia tere by Jeremy Hansen and Jade Kake

Massey University Press, $75