Dec 13, 2018 Books

A son’s poignant tribute to his mother is a reminder that nothing can really prepare us for the death of a beloved parent.

An extract from Dear Oliver by Peter Wells (Massey University Press, $39.99). Peter Wells is a writer of fiction and non-fiction, and a writer/director in film. He has won many awards for his work in both print and film, and is a co-founder of the Auckland Writers Festival.

‘It’s Bessie.’

What else could it be? I enter strange space, feel an almost delicious apprehension that Bess could be near death; it’s followed quickly by a sense of fright. Is she going to vanish from my life?

Bess versus Bessie. Bess is my preferred name: it’s classy, infers a connection with ‘Good Queen Bess’; it was also what her family called her. Bessie is what the name plate says on her studio door. (A name plate that can be easily removed and replaced with another name, from a similar era: Hilda. Mollie. Thelma. Maggie.)

‘I’m afraid Bessie is starting to behave inappropriately.’

I can’t remember if these were the exact words. Nurses, people in public life, have to be so careful of terminology. But the basic tenet was — trouble ahead.

A sense of panic overtakes me. ‘What’s she been doing?’

‘She took her clothes off in the lounge downstairs.’

I feel appalled. Deeply appalled. I also feel pity. Most of all I feel mortification. Shame.

This is what comes from pretending she is Bess rather than Bessie. Bessie is who she really is. ‘Bess the Mess’, as I used to call her, only partly humorously — chagrin stuck in my craw — when I was looking after her seven years earlier and she had the episode which announced her dementia. I was trapped in her townhouse for Easter weekend, trying to answer her psychotic trajectories with reason, as if by simply reducing everything to rationality it would diminish the chaos. After three or four days I was the one who was going insane.

Then she stabilised and slowly returned to her recognisable self. I’m not so sure now if this ‘recognisable self’ isn’t a fiction I have created. I am not sure my mother isn’t in fact an entirely fictional being who I have spent my life creating. I can’t explain this strangely powerful connection of a son to his mother — a homosexual son to his mother. Barthes said ‘my mother is my inner law’. Proust’s idea was that his mother spent her entire life preparing him for her death, readying him for that moment when he found himself ‘motherless’. Alone. (This was foreshadowed by that crisis that opens In Search of Lost Time, where Marcel calls out for his mother while lying in bed.) Barthes talks in terms of abandonitis. It is no respecter of intellectual status, this harrowing, constant need, interwoven as it is with hate and a deep desire to escape. Shut up, Freud, we’re not really interested in your tidy cul-de-sac. We’re in the wide, open prairie here.

But I’m also unwaveringly aware Bessie is only herself, and I attend her and watch her, much as a zoo keeper might attend to an animal he has bonded with, come to love, whose sickness he watches with a queasy feeling in his stomach. There’s complicity, a realisation that he has spent his life caring for the animal but it could not care less. The animal is demanding its own wairua, is maintaining its own obdurate independence, by deconstructing, by manifesting the deep irrationality which is sickness and death.

‘What exactly has she been doing?’

I’m aware my voice is filled with an almost reverent horror. But there’s also something else, a spark of hilarity, even pleasure in knowing that she is making a mess of herself. This is quickly cancelled by a deep sense of pity that she is betraying herself, her presentation of a self. Bessie, who is courteous, almost innately well mannered, who even now tries to introduce me, again and again, to other inhabitants at the home: ‘This is my son, Pete.’

‘You’re all I’ve got,’ she says to me at times when we’re alone. I hate this. Or when I leave, and I bend down to kiss her cheek, she grabs hold of my hand and holds on tightly. ‘Thank you, Pete, for all you do for me. I’m so grateful.’ But when I relax and feel pleased, she adds, ‘Look after yourself. You’re all I’ve got.’

There it is, the toxic mixture of pity, love, blackmail, need.

‘Poor Mum.’

‘Yes, I know. I hate to see your mother like that. She would hate it.’

I recede further into shock. Deep shock. My mother. Taking her clothes off in public. Her old body. Exhibitionism.

‘We got her into her room. She couldn’t make sense of what she wanted to say. She thought she was constipated.’

‘What are we going to do?’

This was the beginning of another stage of her deterioration. I came home and couldn’t tell Douglas. I couldn’t bear to put it into words. I was frightened he might laugh — not cruelly, but because it is horribly funny. Bess, the daughter of Jess, Gestapo officer of the manners police, taking her clothes off in public.

How bad was it going to get? What could I say when people asked, ‘And how’s your mother?’ I couldn’t articulate what was happening to her. All I could say was, ‘Not good. She’s not so good now.’

I dreamt up fantastic solutions. Sedating her. Keeping her in her room. I thought very clearly about suffocating her with a pillow. I went through how I would do it — visit her in her room as I always did. Nobody else was ever there. But I always came up against the snag: I would be observed entering her room and I would be the last person to see her alive. Besides, when I got down to it, I could not live with myself. I also knew she would fight. That incredible willpower that dominated her life, that sped her on, recklessly almost, to her one hundred and first year — she would fight against me stifling her. I could almost feel, in premonition, the slim column of her neck rising up against the pillow. She would kick, maybe even bite. (This is what she does when she starts to undress again during the drinks session a few days later. Has she become a figure of fun? Do they all shrug and laugh about her? Or is it a horrific presentiment of what is to come for them, too? Is it her ‘raging against the dark’?)

‘We got her into the toilet. Then she walked out with her trousers round her ankles.’

I have to laugh then. Anabel does, too. Apologetically.

‘It’s all you can do in the end. Laugh.’

I feel fear and horror. Most of all I feel shame. But also chagrin. I think back to [my brother] Russell’s death and Bess’s — Bessie’s — breakdowns. Both of them took up so much space in my life (I recognise this is a selfish thing to say) with their bravura crack-ups, their showy descents into madness. Then I think further and deeper into whether this undressing is not endemic to our family, like a strain of madness. What is this writing, anyway, but a form of undressing? I undress my family, I even undress myself. It is compulsive, as if my sanity, my life, depends on it. I humiliate my family by revealing flaws, secrets.

Or is it the other side, an inextricable part of the closed, closeted, highly mannered façade we sought or seek to present? Isn’t this form of writing itself the presentation of a façade? I do not download my own pathetic untruths, failures, the sense of time overtaking me and rendering everything I’ve done trivial and senseless, worthless as a piece of space junk.

She is daily growing more and more tired. I think I recognise the look a cat has when its kidneys suddenly stop functioning. You know there is no looking back — or even forward — as the intermediate days will be taken up with the messy, sad, horrible business of preparing for death. I text a close friend: ‘Bess is checking out.’

‘It’s a shame she can’t just drift away in her sleep,’ I say to Anabel over the phone.

She doesn’t reply but I sense there is empathy in her silence.

But this is too tidy. We’re not in a tidy zone now.

I take a photo of her on my cellphone. I put it on silent and archive my mother’s face, as if to record it for when she is no longer there. For days afterwards I gaze at this image in which I can see both exhaustion and a kind of immutable dignity.

But it becomes ‘inappropriate’ as she gets so old — the mismatch between age and desire. Or is it that old people are not allowed the pleasures of sex? Or has it in fact nothing to do with sex and desire? And is the shame I feel — now this is true — because I wonder if I am infected with the same inappropriate shamelessness? One could call it desperation. In my emotionally complicated childhood and adolescence, I essentially shut down. I came out in my early twenties but my sex life, as could be expected, was chaotic. I was always searching for a monogamous relationship founded on intense, almost overpowering love — what I came later to recognise as a folie à deux, perhaps an echo of the love affair between Russell and me, or between Bess and me.

It wasn’t until much later that this spell ended. It seemed to die a natural death, and at that time in my life I became intensely interested in sex, and sex with a wide variety of men. It is not unusual for gay men from the repressive period to experiment with sex later in their lives. This is partly because the natural evolution of desire and play was stoppered by social pressure, laws forbidding it, stigma, shame. So I suddenly found myself as a man no longer possessing the charms of youth entering a sexual marketplace predicated on youth and beauty. This did not deter me. It gave me strength. And while there were humiliations aplenty (if I chose to recognise them as such), I also discovered a depth of sexual pleasure that helped me mature as a human and cast off the thrall, the frozen part, of my earlier life.

Yet the sudden eruption of Bess into a shameless sexual being (even if there was no overt sexual content in it) gave me pause for thought. Was this really what I myself was? A shameless man who had lost touch with what was appropriate? The keen pleasure I felt when I realised I could undress completely and no longer be ashamed about whatever faults my body had: this had seemed to me to be a major transition, even a key turning point in my life. I was lucky in that I had found in Douglas a partner who is loving and constant, who understood the strange malformation of my past. But I also knew the powerful allure of desire and the potential for anarchy it created.

All these complicated feelings were in my mind. The shame was about myself as much as it was about the shame of a one-hundred-year-old mother who had taken to undressing in public.

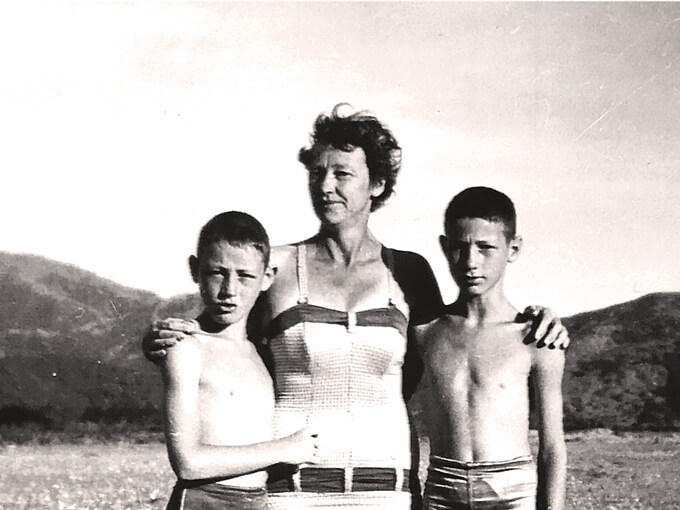

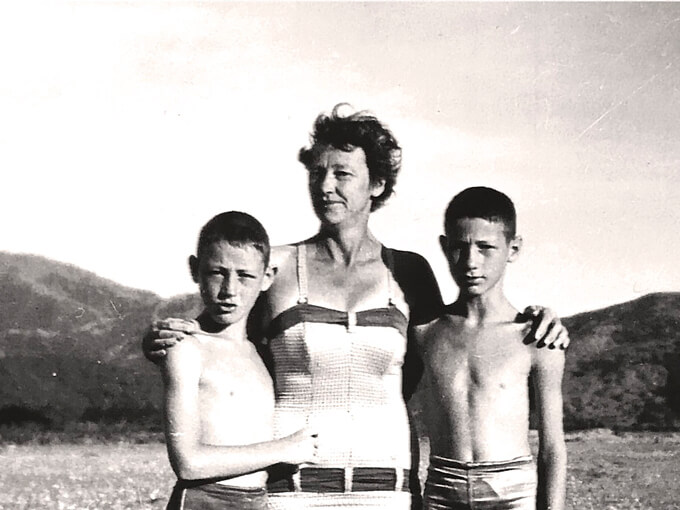

My parents had a separate tent. Russell and I shared a pup tent. My parents’ separate tent was so they could have sex, I see looking back. This explains why they had slipped into an easy, happy camaraderie. Gone was that niggling resentment, that totting up in the book of plaints, regrets, insults. Had Dad forgiven Bessie? Had he made a compromise, decided that he loved her so much that he would forgive, or absolve her, of her wartime lovers? They were happy. It was as if we had different parents — adults who were companionable, friendly. Dad enjoyed building fires and camping; perhaps it took him back to the best part of his war. But what I remember, because it was so unusual, was that we swam ‘in the nuddy’. Nuddy is a childish word that probably desexed the activity, giving it a slightly risqué emphasis. It was daring but lovely.

I still have an image in my head. The waves have made the golden sand as vast as a ballroom floor made of spun glass. In the glass is the sky overhead. We seem to be advancing into the sky itself, a form of heaven. And we are walking forward together, excited by the adventure of being naked — turned back into something almost biblical, a family salved of sin, existing briefly in heaven.

After the incident in the home, I wrote to Shonagh, and she replied: ‘You have said in your letter that she has suddenly been behaving outside her character, so that is a sign of an inadvertent decline due to great age. It is not really Bess doing that, whatever it is. So you do not need to worry or be embarrassed about whatever has occurred. It is not really Bess at all. It is some primeval sense of life and survival that we all may have hidden away somewhere in the recesses of our psyches, long overlaid with good manners, deportment, cultivation and much else, possibly even pretension. It may be an ancient remnant of prehistoric life when we had to find a waterhole by knowing the scent of water on the wind, or to know that danger lurked in the darkness when we had invented fire and could raise a burning stick in the night to show a ring of predators’ eyes glowing in the sudden light. It is an ancient primeval thing, like a howl echoing down a dark valley, so the end must be near, I think.

‘Douglas Bader (DSO, retired).’

Doesn’t this show the beauty of a letter sent at the right moment? I opened her letter up several times to re-read her words of wisdom and comfort. I kept the letter nearby so my fingers could touch it, or my eyes glance at it, as if it were a good-luck token.

I would carry on. Isn’t that what my background told me to do? To persist. This applied to my grandfather after the 1931 quake as much as to his daughter, who at almost one hundred and one had forgotten how to die.

12 March 2017

A young nurse, who is always pleasant, phones me to say Bess has vomited up something like coffee grounds. This is apparently a serious sign. Bess has some sort of internal bleeding, and the nurse seems to be saying she is entering a dying process. ‘Entering a dying process’. How absurd. She is dying.

Immediately I experience an outbreak of anxiety. It is hard to comprehend. Why am I feeling so anxious when I know she will have to die sooner or later, and some rational part of my mind celebrates the fact? It would be better for her to die rather than to enter a deeper state of dementia. Yet I feel an elemental panic. It is as if I was standing on a platform high up in the air and the floorboards under my feet have given way. Abandonitis.

I go down to visit her. She is lying on her side, asleep. She keeps murmuring, ‘Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear.’ Gradually she rises to consciousness, sees me sitting there, and tells me not to stay, to go home. She seems to think I have just driven down to Napier or wherever she thinks she is. Later she says to me, ‘Go, you mustn’t be late for school.’ I say I’m happy sitting there and she should just keep snoozing. I have brought a New Yorker to read and have my iPhone.

She gradually becomes more conscious and I ask her if she would like me to brush her hair. I pick up her 1930s silver brush with her initials elegantly engraved it, the silver almost black with tarnish, and I brush her hair slowly, thinking back to how I used to do this when I was an apprentice pouf. Her skull is so visible now. This seems to ease her. I make a cup of tea, put cold water in it so it doesn’t scald her, and give her a chocolate biscuit. She seems to be hungry. She sits up and sips the tea. After a while she asks me where the toilet is. She makes to get up and I panic at what I might be forced to see. Lecture myself about not being so selfish. She can’t get up from the bed, so I somehow wrestle her upwards from behind, my hands under her armpits, get her walker, and she manages to get into the toilet. I go and stand where I can’t see her. Eventually she finishes and I help her back to the bed.

‘You’re a wonderful son,’ she says. It is heartfelt.

We talk a little more. For the first time she acknowledges her own death.

‘What will you do when I kick the bucket?’

I’m not sure quite what she is asking me. I decide to say, ‘I’ll be very sad, Mum. Very sad indeed.’

I want to say, You have loved me unconditionally in a way no one else will ever do and we have had an enriching friendship. You who were worried I would always be poor as a writer have supported me. You have been a bewildering, spellbinding mother. I will be all right. And I have Douglas, and he understands me, knows what and who I am, is my rock.

But I don’t say that. I say something else, and I don’t know why: ‘Don’t worry, Mum, we’ll meet again when I die. We’ll be together then.’

It is such a curious thing to say, because I am unsure whether I believe this. One part of me, the rational part, sees it as a ridiculous statement. Some other fairy part of my consciousness holds out a hope it is true.

‘Well, let’s not think about that,’ she says in her pithy, down-to-earth way.

Later, settling down to snooze, she says, ‘I don’t know what happens.’

Finally I decided to go. I knew she didn’t want me too near her. She was too sick, probably nauseous. She complained of pains in her feet. I said, ‘I’m going to kiss you, but on your forehead.’

I kissed her on her forehead, right where the brain lies.

‘I’ll see you tomorrow,’ I said.

She seemed quite cheery when I left, or at least as if she had got some consolation from my visiting her. I am not sure if this isn’t an expression of vanity. Just before I left, a nurse came in, plumped up Bess’s pillows in a boisterous way, called her ‘darling’ and said to me as we stood at the door, ‘Knowing Bessie, she’ll probably be right as rain tomorrow.’

I got a sense of how popular she was with the nurses. Later in the evening I composed a funeral soliloquy which included the words ‘of good old pioneer stock’. I meant her peasant strength. Her ability to endure. But also something else to do with her humour, her practicality, her adaptability. Even as an old woman without power she managed to disarm by charm.

27 March 2017

Bess has been shifted to ‘the special care unit’. It’s in response to her undressing. You need to press a buzzer in order to get in, then you enter a neutral zone where another buzzer needs to be pressed to allow you to enter the ‘special care’ area. This is a ring of rooms around a forecourt, the whole area fenced off so there is no possibility of escape. Everybody in the unit has advanced dementia, but they are on the whole peaceful old people who have returned to the simplicities of childhood.

This is a step beyond the hospital, which is where Bess feared to go. Anabel had taken her down there on her own, and had rung and told me, ‘Bessie was peaceful and it went surprisingly well.’

Now I face the task of emptying out her studio, selecting clothes for a single room with a double-door closet. You are encouraged to bring personal items, and there is a box on the door in which you can place family photos — certificates indicating who the person once was.

I feel exhaustion at the thought of sorting through her possessions yet again.

We sit outside in the sun. I chafe her hands and she eventually responds with her customary ‘And what else?’ She also asks me ‘What’s out there?’, indicating with her head the rest of PA, from which she has been exiled.

On my way out I meet the young nurse who had told me Bessie was on the point of dying. I treat her as someone who has betrayed me. The nurses and staff outside ‘special care’ all ask me brightly, ‘How is Bessie getting on?’ I also feel they betrayed her. But the situation is more cut and dried. If she had not started behaving ‘inappropriately’ she would still be back in PA, in conditions which now seem to me paradisial.

Maria, the smiling matron of ‘special care’, says they will put a ‘onesie’ on Bess with a zip up the back so she cannot undo it when she wants to undress. ‘It’s to save her dignity,’ she explains.

I wish she had died.

Sometimes I think of her as she used to be. I see her in motion. I see her walking along energetically, on her way somewhere. She is full of purpose. She also makes small movements with her hands, as if she is in the middle of an animated conversation. She is ‘making a point’.

Packing up her room, throwing things away — I think of all the times I’ve done this — reducing possessions into ever smaller units. In all her drawers, behind cushions, in cupboards, endless tissues she has secreted ‘for a rainy day’. I find a questionnaire from PA: ‘What do you think of Princess Alexandra Retirement Village?’ She has filled it in with shaky but determined handwriting, all in capitals, ‘It is very boring but I suppose that is what these places are.’

Bess with her full engagement book, playing endless bridge, ‘off to a show’. ‘Let’s have a spot.’ ‘You do pour a good G & T, Pete.’

I go down to visit her. I dread the lack of privacy. I always used to take her up to her room so we could have tea together and talk in private. When I walk in, I ask, ‘Isn’t there a family room?’ There is. It’s not much more than a large cupboard and it has surplus equipment in it, but there are two armchairs. I get Mum in there and we sit down together. I close the door.

Surprisingly, she is quite focused.

‘How are you, Pete?’

‘How are you getting on?’ I counter.

She is mellow today and we manage to make a small picnic of chat. It feels, in the circumstances, like one of those days you unexpectedly go out and find the perfect spot, and the sun comes out, and you feel relaxed as time expands all around you.

I mention various family members and she knows who they are. She maintains eye contact and is philosophical.

‘You have a good time,’ she says to me when I stand up to go.

(Translation: I have had a good time, why don’t you?)

Then she says: ‘Look after yourself, Pete.’

(I translate this as: Be wary, I can’t look out for you any longer.)

Then she says, just before I go: ‘You go and do whatever it is you have to do.’

11 April 2017

‘I’m going to die.’

Bess said this five times to the nurse this morning. They tell me this when I come in. I sit with her. She is barely conscious. She is in pain, can’t get comfortable. Is nauseous. I sit beside her, and when she becomes conscious of me it is to deliver her verdict, typically plain and straightforward: ‘I’m buggered.’

She doesn’t even add my name. She has no time for courtesies. Time is running out.

She turns away and tries to sleep.

It’s time she is on morphine but we have to wait for the doctor to come to insert the morphine drip. He is busy, and when he arrives he indicates I may not want to stay in the room. I go and sit in the main room.

I listen to the quiz the nurse aide gives to the variously damaged old people sitting in a circle. None of them is in pain or even apparently unhappy. They exist in the tranquil now-time of childhood. It’s only their old bodies or rather their brains that have betrayed them. I try not to look at an old Pakeha man — he could have been a builder or a carpenter — who holds a doll in the shape of a baby. He hugs it to his chest.

‘What bridge was opened in 1959?’

There is a note of good-tempered belligerence in the nurse aide’s voice.

She repeats the question at least four times.

We hold hands.

‘Owww, your hands are so cold,’ she says in the voice of a spoilt little girl. I weep. We keep holding hands. She sinks into a morphine sleep.

I take my hand away when I realise she is in an uncomfortable position. I hear the nurse asking the old people in the lounge if any of them can sing a song. And suddenly a woman’s voice, surprisingly melodic, starts singing Cockles and mussels alive alive oh.

I find this very emotional. When she sings She died of a fever / and so no one could save her / and that was the end of sweet Molly Malone, the nurse aide says loudly, ‘Oh we don’t want to hear that’, but the old woman’s voice continues to the end: Now her ghost wheels her barrow / through the streets broad and narrow / singing cockles and mussels / alive alive oh.

It seems beautiful to me.

Bess is in her own world now, travelling inwards. I take one or two pictures of her. I don’t know quite why I do it, or even if it isn’t tasteless. But some other part of me is more basic. Storing up nuts for the coming winter.

I realise I’m exhausted. I’ve had two terrible nights of sleeplessness in a row. I can’t explain what’s happening to me. It is as if her soul is being wrenched physically from my body.

Maria, the matron, goes home, saying she will deliver a chair for me to sleep in. It doesn’t arrive.

The young doctor comes by, turning the light on. He says, ‘Bessie’s face still has a good colour. I don’t think anything will happen tonight. Of course we don’t know.’ (He doesn’t say the word ‘die’, which is somehow forbidden — too naked, too real.)

I look at her face in the light and see it is still quite pink. I suddenly feel intensely grateful: I might be able to go home and lie down flat on my bed and sleep. I know her ability to last. And I cannot take another night of sleeplessness. I’m a wreck.

I arrange that they will phone me immediately if there is any change. And as I walk outside I’m aware of the intense sweetness of the living world: plants, grass, sky — all seem miraculously alive, as they seem when you’re tripping. Maybe that’s what I’m doing. As is she.

12 APRIL 2017

The phone goes at 3.40 a.m. ‘Come immediately.’

I get up, dress and drive down there, but can’t get into the building. The doors are all locked; nobody answers the phone. I drive around to the closed front door, which has printed directions to go to ‘York Wing’, but there is no map of where it could be.

I go to the next door, knock on it and wait.

A nurse, passing by, sees me and lets me in.

‘My mother Bessie is dying.’

I get into special care where there is a nurse I have never seen before. She is on the phone.

‘She’s just gone.’

Do I imagine I see a flicker of guilt on her face?

I run into the room and Bess is lying there, so tiny, her mouth wide open, jaw slack. I kneel down by the side of the bed. I find I’m weeping, as if in a separate action which is not related to me. The words I say don’t make sense to me. ‘Oh Mum, Mum, oh Mummy.’ I touch her arm. It is warm. How could I not be there at the final moment? I sit there for a long time, incapable of leaving.

Aggy is in the corridor outside. ‘Phew, what’s that?’ one of the staff says. Aggy says, ‘Do you want to see it?’ The staff member says, ‘Come on, Aggy, we’ll go and clean you up.’

Throughout the morning various staff members come into Bess’s room to say goodbye. I’ve draped one of her coloured scarves over her face. It seemed wrong to leave her like that, her mouth gaping open. (Later I read that you are meant to prop a cushion under the dead person’s chin, so it stays closed. Why did I not have information like this? Because I never thought I would be in that situation.)

‘What a noble woman!’ one of the staff says to me after a hug. This pleases me, and seems to resurrect a Bess who was alive in the world. The young nurse who was so kind to Bess and to whom I was rude gives me a fierce hug. ‘She was so delightful.’ Anabel comes in, and I thank her for looking after Mum so well and for telling me that she was near death not so long ago, so I was better prepared.

I chide myself for not being there. It seems very cruel — I who have watched over her and guarded her to the last moment was not there when she died. I don’t know what happened — why I was called only at the very last moment. But I have to accept it.

Later I tell the two women funeral directors about her being only nine days away from her one hundred and first birthday: ‘She was tough, she was of pioneer stock.’ The funeral director, searching for a suitable cliché, says, ‘They don’t make them like that anymore.’

I leave the room.