Jan 22, 2016 Politics

The National Party is the most powerful political organisation in Auckland. But it doesn’t run the city. And, come the day John Key retires, who’s going to seize the chance to run the country? This summer, the power plays will unfold…

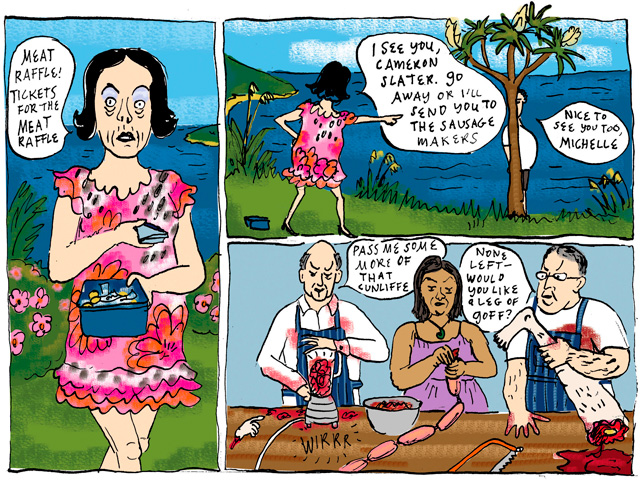

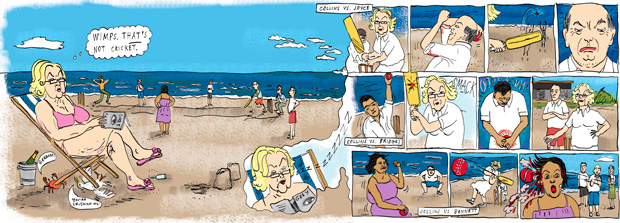

This article first appeared in the January 2016 issue of Metro. Illustrations: Sarah Laing. Photos: Simon Young and Getty Images.

In May 2015 at the Global Women annual retreat, held in the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Queenstown, Michelle Boag jumped to her feet with an impassioned plea. Global Women is a New Zealand organisation of women in leadership roles, and Boag is a PR consultant, confidante of Prime Minister John Key and former president of the National Party. What she said to the 85 women in the room was, “For the love of God, there must be someone here who wants to be mayor of Auckland!”

The very next person on her feet was Judith Collins. She does not want to be mayor of Auckland. She wants to be prime minister, and her recent reinstatement to the Cabinet takes her a step closer to that goal. But last May her prospects were poor. She had quit the Cabinet under a cloud in August 2014 and, even after she was cleared of the allegations of wrongdoing that led to her leaving, the PM had pointedly not reinstated her. It was a signal: Collins was supposed to find something else to do.

In Queenstown, she did not say she wanted to be mayor. On the contrary, she denied it. But her timing was impeccable: she wanted it known she was keeping her options open. She knew it never hurts to keep them guessing.

Collins is possibly the smartest politician you will ever meet, in the sense of political smarts. She’s always working the angles, playing the long game and the short, and she’s better at it than most because she really is smart and because she loves it more than most.

She’s also better at it because she has a purpose. Right-wing commentator Matthew Hooton calls her the only identifiable right-winger in the Cabinet. She has argued, as have Jeremy Corbyn and Donald Trump, that change — therefore progress, therefore social good — comes from the edges.

That’s a slight misrepresentation. It’s undeniable that change comes from the edges. But few politicians talk about that, because the prevailing theory of politics is that to hold the centre is to hold the power.

When you are dedicated to holding the centre, however, as Key and the National-led government have done so brilliantly for the past seven years, you are by definition not much interested in change. The centre is conservative. It’s not regressive — a centrist government will never undo gay marriage, say — but nor will it decriminalise marijuana. It’s where the status quo is preserved. It’s the place where as little as possible happens.

Collins wants change, and that puts her offside with all those in National who would rather remain becalmed in the centre than rock the boat. But that’s not everyone. She’s not offside with cocky upstarts who want to make a difference, because they identify with her. Collins has few friends in Cabinet, but she’s quite popular in caucus, and she’s popular in the business world too.

And because of that, and because she’s formidably skilled in politics and keeps herself in the public arena, Collins is the most important person after Key in the National Party in Auckland.

She isn’t in the inner core but she doesn’t need to be. At every turn she prompts the question: Will it be Judith or can we find another way?

Take the Auckland mayoralty. Michelle Boag does not like Collins. She’s been looking for someone to replace Len Brown since before the last council elections in 2013 — and Collins, until her Cabinet reinstatement, was almost certainly the person on the entire centre-right with the best chance of doing that.

For Boag, though, the question has effectively been: Who will save us from Judith? She asked Ralph Norris; he said no. She asked Rob Fyfe; no again.

And then, at that Queenstown meeting in May, up popped Victoria Crone.

Vic Crone, as she likes to be known, didn’t announce a run for mayor at the Global Women forum, but she did take Boag aside and tell her she’d been thinking about it. Boag didn’t even have Crone on her list, but at last, she had her candidate.

At the time, Crone was CEO of Xero’s New Zealand operation, having been wooed by Xero boss Rod Drury away from Chorus, where she was head of sales and marketing. That was in April 2014 — a mere 13 months earlier.

After Global Women in May, Crone went on to talk to “people in all walks of life” about whether she should stand, although she didn’t tell Drury. He found out about her intentions quite late and from other sources. Even Len Brown’s office knew about it before Drury did.

Crone, who is 42, launched her bid to be mayor at the Mind Lab, a bright-and-breezy IT learning facility with cafe attached overlooking the Domain in Newmarket. It’s a bit scruffy and a bit funky. The room was filled with women in business, people from the digital world and a couple of Auckland Future people — but no one identifiably from National. Boag was not there.

Drury was there, being supportive, still looking shell-shocked. Crone had resigned from Xero that day, and having his hand-picked New Zealand boss walk away after less than two years, to pursue a political goal he had not known about when he appointed her, was absolutely not part of his business plan.

Crone wasn’t introduced, there was no entertainment or promotional video, there was barely even a sense of occasion. She was dressed in a stylishly informal manner, in slacks, strappy sandals with heels and a loose-fitting top. It felt like she’d dressed for Saturday lunch with friends, although when I met her days later at the Xero offices, she was dressed in the same manner. Stylishly informal clothes are what Vic Crone wears to work.

And if you’re her, you have to be thinking, how hard can it be? Because this is what she’s up against:

Phil Goff, the unofficial official candidate of the centre-left, is 62 and wears a grey suit — all the time. Sometimes he takes the tie off. He launched his mayoral bid at the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron in Westhaven, in a room largely filled with other men in suits (most of them from the Labour Party). He projected responsible, centrist, business-friendly experience.

Also, to show he knew about having fun, he had Jackie Clarke as MC. She told jokes in a fast loud voice, working hard to get the energy levels up. She introduced Lizzie Marvelly, who was, she said, “unapologetic about using the F word”. Feminism, that is.

Marvelly sang “Generation Young”, a song that, despite its sentiment, has a melody so middle-of-the-road it would go down a treat in a retirement village. Goff may be fogeyish now, but that song surely pained him — at Marvelly’s age, he was a renegade hippie listening to Jefferson Airplane.

Clarke did her best to get the energy back up again with a version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” that was so hysterical Goff didn’t realise it was his introduction. When he spoke, noting that Fleetwood Mac had played the Vector Arena the night before, he said Stevie Nicks “gives hope to septuagenarians everywhere”. Nicks is 67.

He said his wife didn’t want him to stand: there was “a little opposition from my wife, Mary, who isn’t quite sure this is the right thing for family life”. He started to talk about the entrepreneurial scientist Paul Callaghan, but had a senior moment and forgot his name.

Everyone smiled bravely.

Crone is not in the National Party, although her critique of the council closely correlates to the things said by Boag, Sue Wood, Nikki Kaye, Cameron Brewer and all the other party members I spoke to for this story.

She says she’s all about “fresh thinking”. She criticises “serial politicians”, although she told me it wasn’t a pejorative expression. Quite reasonably, Goff is not alone in objecting to this: politicians on her own side also believe political experience is an asset.

Crone’s message is that she will bring a set of goal-oriented business management skills to the mayoralty. Five minutes in her company and it’s obvious she’s focused, a quick learner and used to getting her own way.

Kaye says Crone “sponges” — she soaks up information and ideas. Whatever the shortfalls of her thinking to date, says Kaye, Crone will fix them. ?And yet, for all the freshness and purpose, there is still the peculiar matter of Contact Energy. Four days before she announced her candidacy — that is, well after she had decided to run for mayor — Crone got herself elected to the Contact board. She was asked at the AGM specifically about a potential conflict of interest, and she assured the meeting Contact would be her “top priority”.

I asked her about that at her launch, and she said Contact and the mayoralty would “jointly” be her “top priorities”. She said she did not think there was a conflict of interest but would have to look at that when the time came.

I asked her again when we met later, and this time she listed her priorities as 1) mayor, 2) her children, 3) other things that would be decided, if necessary, when the time comes.

This is loopy. Contact is a major publicly listed power company that has a complex relationship with the Auckland Council — the mayor cannot possibly sit on its board.

Crone’s decision not to withdraw her nomination for the Contact board after she had decided to run for mayor, and her sliding answers to the question of priorities, shows a lack of political understanding and business acumen. She’s created a stick for opponents to beat her with, and in misrepresenting the situation she will have undermined the confidence of shareholders. She’s just done to Contact what she also just did to Rod Drury: if things work out for her, she will walk away from a major commitment she made to the company.

I asked Crone what on earth she was thinking. She told me some “leading people in the business world” and some “ex-politicians” had advised her it would be okay. That beggars belief.

It also reveals rather a lot about the state of the National Party and its intentions in Auckland. Despite everything, they’re not as organised as you might think.

In October, a group of about 80 National Party members and friends gathered at the Italia Square restaurant in Parnell. They were there to raise money for the party’s new vehicle for contesting the council elections, Auckland Future, and John Key was guest of honour.

Why a new group? Haven’t they got C&R already?

Yes, they have, but National is fed up. C&R, as Citizens and Ratepayers, used to run this town. But when the Super City was formed, it lost its majority, and even in the 2013 election, in its new guise as Communities & Residents, it failed to gain citywide traction.

When Auckland Future was set up, its leaders did not even bother to talk to C&R — although they’re all in the National Party together.

So why doesn’t the party run Auckland? This city is now National heartland. With the exception of the three South Auckland seats and Tamaki-Makaurau, National wins the party vote in every Auckland electorate.

It’s only about a decade since urban centres were heartland Labour. Even in the suburbs where National usually prevailed, Labour still polled reasonably well. In 1999, for example, in the five suburban electorates of Albany, Epsom, Pakuranga, North Shore and Northcote, National gained a total of 16,000 more votes than Labour. In those same electorates in 2014 (Albany had become East Coast Bays by then), National gained 80,000 more votes.

When Labour looks at those numbers, as centre-left strategist David Lewis says, it knows “it has to win those votes back or it cannot form a government”.

When National looks at those numbers, it asks itself, “If we’re so popular, why the hell can’t we win the council?”

It particularly asks itself why it can’t win the Shore. In the council election of 2013, the independent rightist candidate John Palino won the mayoral vote in all five of the ward seats north of the bridge. Yet the centre-right holds only one seat in those five wards.

And on it goes. The Waitemata ward contains 70 per cent of the richest suburbs in the city, but is represented by the unreconstructed old lefty Mike Lee and a local board full of Labour and Green types. Why hasn’t Waitemata turfed them all out and voted blue?

On the whole 21-seat council, seven councillors belong to the National Party and three more are Act or Act-aligned. Yet they don’t form a bloc. Only five consistently oppose Len Brown’s programme, and even they are in at least three different factions.

Brown, on the other hand, commands loyal support from seven councillors, and quite frequent support from another four — including three of the National members. There are five more who float.

Brown doesn’t even need all the centre-left votes, which is a good thing for him, because he can’t rely on them. Mike Lee is so vehemently opposed to Brown, he calls councillors on the left who support the mayor “collaborators”.

One reason there are no strong factions on the council is that Brown really is a centrist, and a skilled consensus builder, too. Most councillors accept the approach and do not welcome the idea they should be whipped into party alignment for the sake of it.

But they are also motivated by the wishes of their constituents, and by personal predilection. Many are former mayors or leaders from the old legacy councils and they’re not inclined to take orders from anyone.

The centre-right on the council is actually bristling with people who might have fancied they could unite the opposition to Brown, but despite their best efforts Christine Fletcher, Cameron Brewer, Dick Quax and George Wood have failed in the task.

To the National Party hierarchy, it has become clear that somebody needs to save the right from itself.

The job fell to Kaye, the Auckland Central MP, and list MP Paul Goldsmith, both government ministers. The first thing they did was call Sue Wood. Like Boag, she is a PR consultant and former party president. Wood wrote a paper for Kaye and Goldsmith setting out what she thought was wrong. In essence: no policy platform and no discipline.

She gets pretty fired up about it, she says, and you can see why. What are people doing in politics at all if they don’t have a programme and an agreement to stick together to achieve it? She says she’s been meeting the centre-right councillors, one on one.

When I met her, in her Parnell townhouse, she projected soft charm and a steely resolve. It’s a rare skill, to utilise both at the same time, and she will have been far more than a match for most of those councillors.

Wood also wrote that Auckland Future needed its own independent board — a contrast with C&R, where another former National Party president, John Slater, used to rule the roost. But when Auckland Future was publicly launched in mid-October, the board was led by Joe Davis, a deputy chair of the party’s powerful northern region. He didn’t last long. Peter Tong, a medical specialist, is now chair. The Cameron Slater gossip is that Davis wants to become East Coast Bays MP when Murray McCully retires.

Meanwhile, Wood has been appointed a fulltime organiser for Auckland Future (she told me she is unpaid) and Hamilton-based party activist Megan Campbell has been commissioned to draft the policy. Campbell calls herself a “liberal blue” and is a close ally of Nikki Kaye.

Wood says she’s met Vic Crone twice in relation to Auckland Future. There’s no plan, at this stage, for a formal relationship, but that may change.

Will Auckland Future work? The disunity on the council runs deep. Brewer, a party member and councillor for the Orakei ward, is sceptical. “Anything with ‘Auckland’ in the name,” he says, “they haven’t got a chance north of the bridge.”

(Brewer is retiring from the council. He’s moved to Riverhead, which is in Key’s Helensville electorate. Yes, he is interested in the seat.)

In fact, north of the bridge, where National is most keen to restore the natural blue, Auckland Future has already selected the first of two candidates for the Albany ward. Lisa Whyte is a member of two local boards, but she is also a failed council candidate, and she’ll be standing this time against the very people who beat her last time.

In Maungakiekie-Tamaki, Denise Krum is a safe and obvious selection: she’s the sitting councillor and is expected to hold her seat. Krum has jumped ship from C&R, and used to have strong parliamentary aspirations.

Elsewhere, it gets messier. In the south, several centre-right councillors and aspirants are competing for the nominations — and some may end up standing against each other. And in two key isthmus wards, Auckland Future won’t stand at all. One is Orakei, where local board chair Desley Simpson will take over the seat from Brewer. She’s the wife of National president Peter Goodfellow, and is likely to become the leader of the new council’s centre-right grouping — even though, curiously, she signed on with C&R instead of waiting for Auckland Future. That was strangely uncoordinated.

Orakei is a hotbed of blue intrigue. Brewer was unchallenged last time round, but in 2010, he won the ward as an independent, beating John Slater’s patrician C&R candidate Doug Armstrong and dividing party allegiances.

This time, Orakei Local Board member Mark Thomas, a loyal party member, is standing for mayor, although he has no apparent support from anyone on C&R, Auckland Future or the party itself.

Desley Simpson is a “character”. She has the kind of kitschy flamboyance you’d expect to find in a Westie, not a Remuera maven, and while deputy mayor Penny Hulse says she is “easy to caricature”, she also warns: “Don’t underestimate her. She works like a Trojan and she is not a puppet.”

Hulse likes Simpson. “I admire her ballsiness. When she signed the condolence book after the Paris bombings, she wrote, ‘It felt right to wear Louis Vuitton today.’”

Not everyone is enamoured. Christine Fletcher won’t like taking orders from her, and nor will George Wood. And Michelle Boag is not a fan at all. “Let’s be honest,” she told me. “She’s chair of a local board. It’s a big step up. I know she’s very ambitions, but I don’t really think she’s a leader.” Ouch.

Boag thinks Bill Ralston would make a good caucus boss. Ralston is standing in the Waitemata ward as an “independent”, although he’s also been an adviser to the National government and particularly to Kaye. They’re good friends. He doesn’t rule out caucusing with Auckland Future.

Why does Bill Ralston want to be a city councillor? Because door-knocking for votes will be more fun than wandering along Ponsonby Rd in your slippers to walk the dogs? Or because he is, as Kaye says, “a disruptor and an innovator”, and Auckland Council sure needs that?

Ralston is not a details person. Even he says that. I asked him about the big Franklin Rd redevelopment project, which is about to start. Which of the three proposals did he like best? He said he didn’t know much about them. He lives on Franklin Rd.

Good on sound bites, though. “If Len Brown can get his own way, how hard can it be?” The council-owned golf courses are an “outrage”. The cycle lobby is “ferocious”.

Kaye says Ralston has “the best instincts of middle New Zealand of anyone I know”. Boag says his lack of interest in detail is irrelevant. “That’s not important for leaders. Leadership is about force of personality and that’s all it is.”

Simpson v Ralston, then, with lashings of Fletcher? Assuming Ralston wins, of course. He was going to be competing against Shale Chambers, a highly regarded Labour policy wonk. But Chambers lacks the charisma to stand any chance against Ralston, and the City Vision team (Labour and the Greens) knows it. Mike Lee was going to retire, but he may be the only person they’ve got with any chance of keeping Ralston out. They know that too.

Despite the fractiousness, forming a centre-right caucus on council in order to control the city shouldn’t be impossible. But that’s not the biggest issue. What’s that caucus actually going to do? What will Auckland Future stand for if it gains power?

National, remember, has a remarkably mediocre record governing Auckland in recent decades.

The party is like a braided river with many tributaries: farmers, though not so much these days; compassionate conservatives like Bill English; neoliberals like Judith Collins and Matthew Hooton; centrist managers like John Key and Steven Joyce.

There is now also a strong group that might be called “new ethnics”. Chinese, Korean, Indian: all those ethnicities are in Parliament, as National MPs. Labour has none.

If Phil Goff wins the mayoralty there will be a byelection in Mt Roskill and the result is not obvious. Goff holds the seat with an 8000 majority but National won the party vote in 2014 by 2000 and in Parmjeet Parmar it has a good local list MP. She’s a doctor, and is highly regarded.

Asian communities have become more business focused and involved in politics. National has welcomed them; Labour has been dog-whistling over “Chinese-sounding names”. It’s very easy to see where all that is going to lead.

There’s another new group in National: the new urbanists. Think Kaye, and possibly also Vic Crone. They’re socially and environmentally progressive, and committed to economic strength through city-building. Like centre-left urbanists they’re likely to ride a bicycle, but they’re also more likely to support asset sales.

Kaye has been upholding the values of new urbanism since she was first elected in 2008, and when the government proposed to allow mining on Great Barrier Island in 2010, she got “slammed” by senior Cabinet ministers for opposing it. “It wasn’t an easy time,” she told me, but the PM publicly supported her right to say no, and that helped. Besides, she won.

More recently, Kaye has helped lead opposition to port expansion, despite the government showing no interest in becoming involved.

Will Auckland Future adopt her views on issues like this? It’s unlikely, because it will want to have broader appeal. Kaye says she expects to disagree with “20 to 30 per cent” of the policy, when it’s announced in late summer.

In National’s braided river, there’s a lot of commingling. Few politicians are purely one thing and not any part other. Yet everyone shares the belief that they are, or should be, the natural party of government. They believe they are better at it running things than anyone else, and therefore that it is their historic role to do so. Some of them think it’s their birthright.

It seemed, for a while, that one of Helen Clark’s greatest achievements in her nine years as PM was to destroy that idea. One of John Key’s greatest achievements has been to reinstate it.

So what happens when John Key goes? I talked to a lot of party members for this story and few were prepared to put anything on the record. Everyone believes he will stand for a fourth term, and win: “He really wants to beat Helen Clark’s record,” said one insider. Then he will retire.

There’s no obvious successor, no one who can claim to being an admired leader-in-waiting. No one has the numbers.

Paula Bennett wants the job, but there’s a theory she’s been over-promoted by Steven Joyce to expose her limitations. Jonathan Coleman, ranked fifth in Cabinet, has handled his Health portfolio with aplomb, but he’s a quiet Don McKinnon type: deputy, not leader.

Simon Bridges, now Transport Minister, has modelled himself closely on Key and has both mongrel and charm, but to date has failed to impress with any real sense of depth.

Joyce wants it but few in the party think he would be electable. After the Northland byelection, which Joyce ran and comprehensively mucked up, he’s not half so revered.

And there’s Judith Collins, who might not win a general election if she succeeded Key as prime minister, but sure would know how to rain down the fire and brimstone as leader of the opposition. She’s the galvanising one.

Most of the punditry inside the party goes like this. Key will win in 2017 and retire in 2018 or 2019. The new leader will probably lose the 2020 election and be quickly replaced, either by someone from the next generation — most likely Bennett or Bridges — or by Collins.

Who would the interim leader be? Bill English. He’d get to be prime minister, an ambition he is said to harbour still, and there’d be no shame, after his distinguished career as Minister of Finance, in taking one for the team. Of course, he might just think that was madness.

Here’s the thing about National, though: there’s no one else like John Key. When he couldn’t hammer in a nail on a hoarding during the Northland byelection, the clip went up on YouTube. It’s been watched 1.3 million times. And it didn’t hurt him.

The Xero offices, above the Paddington pub in Parnell, are surprisingly bleak. I’d expected character of some kind, to match the motivational jargon that spills from modern companies like this, but they’re barren. No distinguishing features, no aesthetic edge, not even any artwork to enliven the walls. An anonymous shell in which to conduct business.

Crone gets someone else to make the coffee, not pulling rank but because she doesn’t trust her skills with the Nespresso machine. She tells me about a survey that reveals only 15 per cent of Aucklanders “trust the council”. She says there’s an 83 per cent correlation of that figure to trust in the mayor. Of course, Brown is not standing for re-election.

There are two widely held views in Auckland. One is that the city has blossomed. It’s an exciting place to live and work and play. The other is that the council is wasting our money: spending is out of control and so is debt, and rates are too high.

They can’t both be true. Or can they?

The election next October — for the ward councillors and local boards as well as for the mayor — will be won by candidates whose messages around those two ideas make the most sense.

Crone and Goff were interviewed on Morning Report in mid-December. She talked about “perceived wastage”. She’s careful to use the qualifier. Goff agreed. “I would stop duplication and waste,” he said. “I think local government has to do more with less. I think the council has lost the confidence of the ratepayer.”

They tag-teamed each other. Interviewer Susie Ferguson asked them to name one thing they love and one thing they hate about Auckland.

Crone said, “I love the accessibility of the beaches. I hate the traffic.” Goff said exactly the same thing, although it did take him 127 words.

But of course there are differences. She’s open to debate on asset sales, while Goff has declared his complete opposition to the sale of “strategic assets”. What about golf courses? Goff thinks that should be looked at; Crone has not said anything yet.

Crone told me she has experience (as head of sales at Telecom and head of sales and marketing at Chorus) in turning organisations into the right size for them to function efficiently. That’s not language you’re likely to hear from Goff.

She says things like “my skillset is in engaging communities and driving outcomes”, and in the Xero office she jumped up to the whiteboard to draw diagrams.

In fact, her conversation tends to be speech bubbly, as if her thoughts are like those little clouds people draw on the board.

As examples of “fresh thinking” to resolve traffic congestion, she talks about driverless buses and working from home. But such “solutions” are far less radical than they seem. “She’s saying we don’t need to change anything because technology will do it for us,” says transport activist Patrick Reynolds. “It’s a do-nothing position.”

I asked her, what about a big programme to get parents to stop driving kids to school? She doubted it would work.

The most popular message in Western politics right now is: we need change. The system is broken and someone needs to come in and fix it. Trump. Corbyn. Collins. Crone.

Politicians like Goff, with experience of actually running governments, are in despair. How do you defend what has suddenly become indefensible?

And yet in many ways it is indefensible. Crone is right to say we deserve better. Can she make it better? It’s way too early to know. She hasn’t started well. But the people who know her call her a fast learner. Let’s assume that’s true.

Can Goff learn? Can he grasp the historic moment, utilising his experience and losing his institutionalised caution? Will this, finally, be his finest hour? We don’t know that either.

And what about the National Party? They’re not a party of change, but they can be pretty good at looking like one. Cameron Slater loves to sneer at Nikki Kaye, which can only be valuable for her and for the party. She gives it a veneer of modernity, and over time it could become far more than a veneer.

On January 27, John Key will make a major speech in which he will commit to funding the City Rail Link. Auckland’s time may finally have come.

So will Auckland Future (and Vic Crone with them) be a force for progress? Or is there still a risk National will resume its usual historical role in the city, and slump into mediocrity? We don’t know that either.