Dec 3, 2014 etc

At $5000 a week, the Capri alcohol and drug treatment centre has brought Hollywood-style rehab to Auckland. Its clientele has included society girls Millie Holmes and Keita Nobilo, MP Mark Peck, doctors, dentists and millionaire businessmen. But what really goes on inside Capri — and why are its competitors so suspicious of it?

This story first appeared in the April 2009 issue of Metro. Photos by Adrian Malloch.

Tom Claunch is Charlton Heston in Ralph Lauren. He is Rolex and diamonds, protein shakes and vitamin supplements, treadmills and tan. A preacher without a pulpit, staunch Tom Claunch knows right from wrong, black from white, heaven from hell. Follow me, says Tom Claunch, and you will be saved.

For 10 years, Claunch has been the public face of an intensely private service — drug and alcohol rehab for the middle class at Auckland’s Capri clinic.

To some, the Alabama-born recovered alcoholic is little more than a bombastic, blow-waved blowhard, a Southern chauvinist pig, a self-righteous self-publicist with a history of attracting controversy. They point to a TV3 exposé in February 2006 that showed Claunch acknowledging he had dispensed to a detoxing patient drugs prescribed by a Capri consultant doctor who had not even seen the woman.

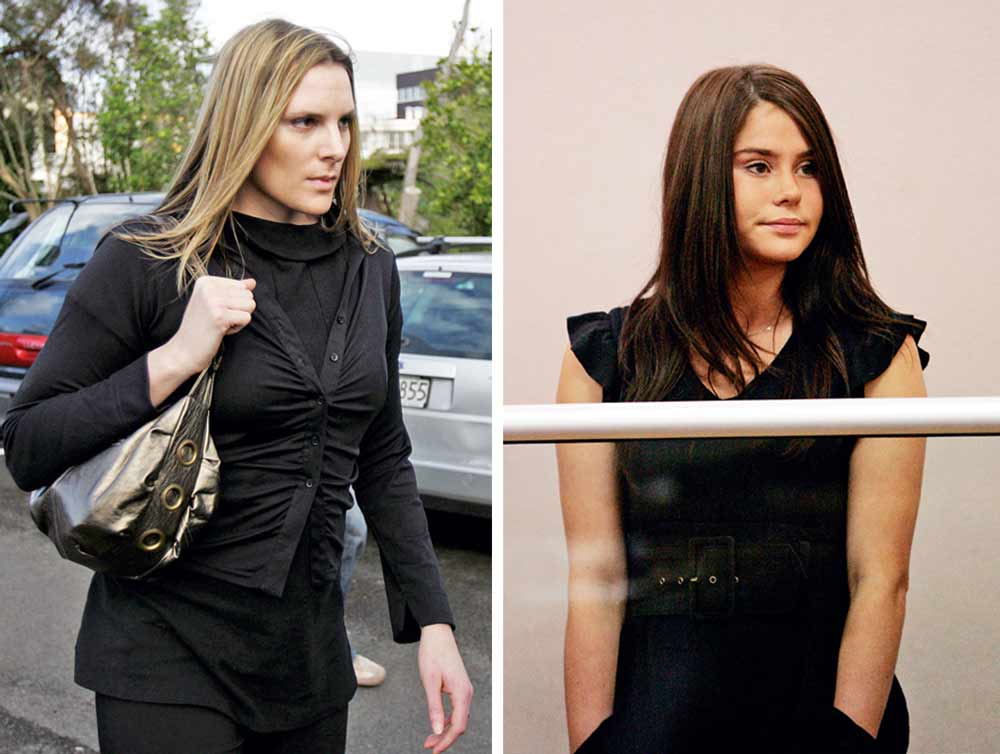

Critics also say it’s a no-no to talk about former patients as Claunch did about Millie Holmes last year, when he not only commented on her re-arrest on P charges, but finger-wagged in the newspapers, “I told you so.’’ And they claim he sexualised vulnerable addicts by telling the media Capri was treating “six absolutely drop-dead-gorgeous, 20-plus females from very prominent families’’.

And now Claunch, 69, has done it again. In December, he married glamorous 50-year-old June Venter, an alcoholic and former Capri client who continues to use the clinic’s after-care services — capping a romance that sparked an internal investigation and over which he offered to resign. The same month, he stepped down as director of the programme, handing the reins to social worker Dale Smith, the son of Capri’s businessman founder Guy Smith.

His departure came two months after that of Venter’s primary counsellor at Capri, Caroline Williams, the woman who blew the whistle on the relationship. She says that in September, a week after “vehemently’’ raising her objections to Claunch’s actions and demanding he be fired, she herself was sacked, along with two other staffers, as the clinic’s client numbers fell. She was told the clinic could no longer afford her services.

Dale Smith headed an internal inquiry into Claunch’s behaviour. “My finding was that I did not believe Tom’s practice was ethical in this situation,’’ he says. While he made “corrective recommendations’’, Smith says, the clinic could not take an employment case because there was no complaint from Venter, who “vehemently refuses to accept she is an injured party”.

Claunch remains an adviser at Capri, living on-site with his new bride and running daily motivational groups with its eight to 10 clients. Claunch appears bewildered by the fuss and outraged that anyone could question him or the relationship.

“I got a little angry about it because of people taking someone like myself who’s dedicated my whole darn life to this field and getting petty over something that I knew there was never any validity to. It’s so ludicrous to me. Here’s a 50-year-old woman and a 70-year-old man and people are acting like we’re some hormone-driven sex fiends. It’s just bizarrely stupid, if you ask me.’’ He says he was never his wife’s counsellor and calls those who raised it “busybodies’’.

“It’s so ludicrous to me. Here’s a 50-year-old woman and a 70-year-old man and people are acting like we’re some hormone-driven sex fiends”

The “busybodies’’ say the golden rule for sexual relationships in a therapeutic setting is either don’t have them at all, or wait two years before embarking on them.

Guy Smith says criticisms of Claunch in New Zealand drug and alcohol treatment circles are motivated by jealousy. “I know people don’t like him in New Zealand. It’s American cringe. But he has helped more people in New Zealand than anyone else. He has 37 years of knowledge. He will die on the floor looking after people.

“People who dedicate their lives to something like that are unique. He is charismatic. He is inspirational. He lifts people up and says, ‘You are not a second-class citizen, you have a disease.’”

Asked if he had been worried about Claunch’s relationship with June Venter, Smith says: “Of course I was, but what do you do? How do you stop lovers?’’

He says the clinic took all the appropriate steps to have the relationship investigated and cleared. “If anyone said he was a womaniser, that’s ridiculous. He’s worked here for hour after hour, seven days a week. He’s never gone out… A very lonely man.’’

Lonely, perhaps. Polarising, definitely. Popular, not particularly. So has Tom Claunch gone too far — and what does this all say about Capri?

If Capri clients are not drunk or high when they walk through its filigreed white wrought-iron gates for the first time, they might feel as though they’ve stumbled through the looking glass.

The path to the front door of the former family home in Waipuna Rd East, Mt Wellington, is dotted with homily-spouting animals. The donkey with green flashing eyes brays, “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail,” the chained crocodile with Peter Pan’s alarm clock in his jaws croaks, “Once was hooked but now I’m free,’’ and even the baby elephant chips in, “Never, never, never forget how BAD it was.’’

Gilded lions prance around a swimming-pool-sized spa in the conservatory where group sessions are held, whopping gold-and-crystal chandeliers grace the foyer and most main rooms, and rearing horses guard the rear gate to the Waipuna Lagoon.

Capri feels like Dynasty on steroids. The eccentric style is that of the home’s long-time owner, Guy Smith, a property investor, alcoholic, former car salesman and women’s hairdresser, who until January lived here with his wife Sue. They shifted out so the clinic’s main treatment facilities could be transferred from next door into their residence, freeing up the original clinic base for Tom and June Claunch to use as a home. (Claunch had been living in a “doggone laundry room’’ in the basement that once had been so damp that mushrooms sprouted under his computer table.)

When Tom Claunch helped Guy Smith get sober 10 years ago, the Capri dream was born. Smith had been into treatment so often that he called himself an “international detoxer’’. Seven months after Claunch helped him to get dry, Smith bought the house next door to his home to set up a programme to “treat people like me’’. Claunch became the clinical director and Smith a lecturer and “recovery coach’’. Sons Dale and Aston Smith joined the staff in subsequent years — Aston as a recovery coach and now administration director, after his own battle with drug addiction. Dale’s wife, Michelle, a primary school teacher, is also on staff as a family and children counsellor.

There is criticism among Capri’s competitors of the credentials of some of its counsellors. One is convicted drug dealer and former panelbeater Brent Smith, 46, who began counselling at Capri last November just 13 months after his release from jail and less than two years after he stopped abusing methamphetamine. So far, he is a Capri success story.

Smith was bailed to Capri in February 2007 after his second drugs bust. His devastated family — he is the son of former Ombudsman and prisons boss Mel Smith — paid more than $20,000 for his eight weeks of treatment before his sentencing. In jail, he studied an Open Polytechnic course in psychology and, once released, took a handyman job at Capri, continued his studies and quickly began taking sessions as a recovery coach before moving into counselling.

While former addicts often become counsellors — at Auckland’s Higher Ground treatment programme, for example, 60 per cent of its counsellors are in recovery — most publicly funded centres require a minimum of two years’ sobriety before employing an addict in that role.

While Brent Smith doesn’t think the transition from addict to counsellor has been too fast, he acknowledges that living and working at Capri has its drawbacks. “I’m still involved with the same sort of people — addictive people.’’

Dale Smith says Brent’s “inside knowledge’’ is invaluable for clients who quite often comment, “We can’t fool you, can we?’’

Brent Smith does not underplay how hard it is to let go of meth — particularly for young people. “The drug gets into the rewards system of the brain where the neurotransmitter dopamine is produced. It spikes the production of dopamine to 1200 units. The normal reward process, like orgasm, peaks at around 120, cocaine is about 300, the opiates are just over 200 units. You take away the drug and the brain isn’t producing the dopamine, so everything is dark and grey and you can’t see purpose or beyond the day. It’s a dark place to be.’’

The first day Metro visits Capri, which is now run as a charitable trust, 10 patients are in residence — a full house. Capri needs 1.7 new patients a week to break even. When it laid off three staff in September, it was getting only one new patient a week and was losing $60,000 a month.

“Parents… say, ‘We don’t want our son or daughter going into treatment with their dealers and gang people… and getting worse.”

Today’s group includes a doctor, a lawyer, a “very prominent’’ businessman, the mid-20s son of an extremely wealthy New Zealander, and the daughter of a millionaire businesswoman in Australia. “All of these people are who we’re targeting,’’ says Claunch. “They are middle-class and professional people who have a desire to get well. If you talk to the young people’s parents, they say, ‘We really don’t want our son or daughter going into the treatment programmes with their dealers and late-stage crims and gang people and learning how to use drugs and getting worse.’ Now that probably doesn’t happen, but the parents think it’s true.’’

A few weeks ago, says Claunch, Capri treated a surgeon who came in for two weeks to detox after falling off the wagon despite six years’ sobriety. After that fortnight, he went back out and did a week of operations before returning to finish his treatment, apparently without his employers knowing where he’d been.

Is that taking flexibility too far — and should his supervisors or hospital have been told? Capri’s medical consultant, Dr Greig McCormick, told Metro he had a statutory obligation to talk to the Medical Council if he knew a colleague was impaired. “I talked to him and didn’t consider him to be impaired.’’

If professionals like the surgeon didn’t go to Capri, says Claunch, half of them wouldn’t go anywhere. And then they’d keep deteriorating until they “hit rock bottom’’. Capri appears to offer the more comfortable awning above the concrete pavement.

Wednesday nights are family-group nights at Capri and the no-exit street outside is lined with Mercedes, Audis and BMWs. About 40 husbands, wives and parents hear Claunch speak in the lounge. The group Claunch jokingly calls “the despicable drunks and disgusting drug addicts’’ adjourn to the conservatory in a separate session with a counsellor.

“We had a lady here who said to me, ‘You mean I can’t even have a drink at my daughter’s 21st?’ I said, ‘No, you can’t. How old is your daughter?’ She said, ‘Five.’’’

Multi-carat diamonds flash across the room. A young mother cradles a baby. A slim grey-haired mother takes copious notes. Claunch outlines the Capri programme and its abstinence-based principles, talks about the importance of the “black book’’ clients fill out daily about their feelings and plans, and how the addict’s lifestyle has to change to achieve sobriety. “We had a lady here who said to me, ‘You mean I can’t even have a drink at my daughter’s 21st?’ I said, ‘No, you can’t. How old is your daughter?’ She said, ‘Five.’’’

There is a ripple of laughter. It doesn’t last for long.

As the meeting ends, Claunch gets word that a former client, who went through Capri six months earlier for alcoholism, has died, apparently of a drug overdose. He looks as though he wants to cuss.

It’s ironic that in a service where confidentiality and discretion are all-important, Capri has been publicly defined by its clientele — glamour girls Millie Holmes and Keita Nobilo and MP Mark Peck among them.

“I’ve been sober now for four years,’’ says Peck, who left Parliament in 2005, “and I attribute quite a lot of that to the month I spent at Capri. It wasn’t cheap, but it was a small price to pay. I was going through a lot of fear. I had a high-profile job, was a public figure and I felt as if I needed a bit of space. It worked for me.’’

An alcohol-fuelled car crash forced him into treatment. “Lying upside-down in a broken car on the Queenstown-Invercargill highway was my epiphany. The façade I had put on for quite a period crumbled.’’

There was no magic about what Capri offered, he says. “For me the treatment was the ability to sit down and talk to other people with the same problem. I felt embarrassed about the opulence of the surroundings. I couldn’t have cared less if it was a tent on the Desert Road… it wouldn’t have bothered me in the slightest. I would have gone anywhere.’’

On reflection, he says, he was so motivated “I probably could have done it without Capri. I was so desperate that it wouldn’t have mattered where I went, but I’m grateful that I got the time I did there.’’

Intriguingly, Peck’s ties to Capri after four weeks’ treatment remain strong four years later. After our interview, he calls the clinic to warn its staff about the questions the journalist is asking.

Two years after her very public drugs downfall on P charges, and on remand on a further methamphetamine charge, Millie Holmes says she no longer wants to talk publicly about her time at Capri. Heiress Keita Nobilo, of the famous wine family, who was in treatment at the same time, told Metro in an email that while she, too, did not want to speak about her treatment, she was doing well and grateful for Capri’s help.

Broadcaster Paul Holmes says he doesn’t know how Millie is doing now, but in those dark days after her arrest there was nowhere else but Capri to go. “My daughter’s arrest happened on a Sunday, out of the blue,’’ he says. “It just hit us like a train wreck. Can I describe the process of getting to Capri versus somewhere else? Easily. There is nowhere else. There is nothing else as far as I know. There is nothing else with a track record, nothing else that has been around as long. There is nothing else.’’

“All I say is, thank Christ it was there,” says Paul Holmes. “Now of course it’s not cheap, and I’m very lucky I could afford to pay”

Holmes sent Millie to his wife’s sister to detox, but at the end of six weeks she was admitted to Capri. When he dropped Millie there for the first time, he found the environment “reassuring’’. “She was shown to a little double bedroom. It was homely, it was feminine, it was comfortable. It had a place for you to put your pictures and precious things. All I say is, thank Christ it was there. Now of course it’s not cheap, and I’m very lucky I could afford to pay. But they don’t chase you hungrily for bills and they make it clear to you that should she ever need to go back, they will take her in, and I was under the distinct impression that up to a year or couple of years there would be no more charge. They are not, I believe, voracious.

“They always showed my daughter kindness and understanding and patience and they showed the same to us. You can only offer support and love and love and love again. Until hopefully a person wakes up to themselves.’’

While $5000 a week is often quoted as Capri’s price, Guy Smith says clients coming in for three to five weeks will usually get a week thrown in free. The price also covers a year of extended care — weekly evening meetings and an open-door policy, meaning former clients can join therapy groups with current patients.

Holmes admits “at least one of our family is of the view that it’s a bit loose out there, that people can come and go a bit easily. It bothered me, for example, that my daughter got a cellphone so quickly. The worst thing for someone in that situation is to be in possession of a cellphone, I would think. A cellphone is anarchy. A single addict is a cartload of monkeys. You put 20 addicts together and you’ll have a truck and trailerload of monkeys.’’

Claunch says families are often looking for something more like jail than treatment. “They want long term, they want it harsh. They talk about boot camp and teaching discipline. They think they are bad people needing to be good rather than sick people needing to be well.’’ He says if clients don’t learn how to make decisions, follow directions and be responsible while in treatment, the chances of them doing it when they’re out is “practically zero’’.

Holmes says the fact a private facility has to exist at all is an indictment on the health system. What’s desperately needed, he says, is more free, public detox beds and rehab facilities. “Should there be a place for pampered little rich bitches? No.’’

He is aware of the criticisms that some Capri counsellors don’t have the credentials for the work. “I don’t really know what their qualifications are but I know the principal people have been to hell and back. I know they’re real. I know they’re true grit. You can have all the bloody medical degrees and qualifications in the world, you can have the flashest psychologists and psychiatrists in the world, but if they don’t understand addiction in their heart, they’re as useless as tits on a bull. It takes addiction to understand addiction.’’

Tom Claunch understands addiction. He found sobriety in an Alabama “insane asylum’’ 37 years ago and has devoted his life since to helping others get dry and to training addiction counsellors. The son of a colonel who fought in the Second World War, Claunch spent much of his youth on US military bases. His family were God-fearing — grandfather was a Baptist preacher — but they attended many different churches, including non-denominational services on the bases.

Ask him to describe his religion today, however, and he thunders that it’s “the silliest question I ever heard. I’m just a bona fide Christian. How do you describe a religion? I hate it when Kiwis get all secular and start putting people down who have a decent belief. It just irritates me because I come out of a culture where the exact opposite is true. We tend to wonder why people don’t have a belief… if you come from the Bible-belt where I grew up.’’

I try a different tack. “Well, there’s obviously a wide range of how people choose to worship…’’

That fares no better.

“Do you go to church?’’ he asks.

“No.’’

“Have you studied the Bible?’’

“No.’’

“Then that question is a non sequitur. You don’t know what you’re talking about.’’

After a further history lesson about Abraham, Jews, Christians and Muslims, Claunch stops suddenly. “I don’t mean to be condescending or anything, I have a difficult time with people criticising anything…’’

“Who’s criticising?’’ I ask. “I haven’t offered one word of criticism.’’

You don’t argue with Claunch. He baulks at questions about his Southern roots and how he adapted to New Zealand culture. “That’s a rather racial statement — you don’t know a thing about me,’’ he snaps.

Asked what it was like growing up on military bases, he says, “That’s a very strange question.’’ Likewise, “How did your alcoholism start — were you always aware you had a craving or was there a trigger?’’ attracts more scorn. “Would you mind getting educated occasionally?’’

Then he launches into the genetic links to alcoholism. His maternal grandmother was a bad alcoholic, her brother was an alcoholic, one of her sisters committed suicide. “I had massive problems from the first drink I had at 17 till the last one I took at age 31.’’ At 17, he’d gone out with a bunch of mates. They’d parked the car and drunk vodka and orange. “I got drunk and disruptive enough that they brought me home and propped me up against a tree in the front yard and left me there.’’

He began drinking in earnest at university, but when he began teaching, he became unemployable. “I was getting drunk, missing work… I was big into what they called in south Alabama ‘heck-raising’. It’s a nicer word than hell. I had always wanted to be a good guy and to pay my bills and get a decent job and find a good wife and have some kids and be honest and trustworthy and have friends, but I was never able to do that until I got sober.’’

Claunch’s first wife stuck by him during his alcoholism and early years of sobriety — they had two kids, but amicably divorced after 21 years. He later wed a psychologist, but their marriage ended in the mid-1990s before he moved to New Zealand.

The man who brought Tom Claunch here was former US Navy commander Jere Bunn. They’d met in the 1970s when Bunn was commanding officer of the Navy treatment centre in San Diego and Claunch was president of the then National Association of Alcoholism Counsellors (NAAC).

Bunn says he wishes he had never brought Claunch to New Zealand. “I had an inkling that Tom was difficult to deal with ahead of time but I had the arrogance to believe it was something I could control, so I’m just as much at fault as he was.’’

Bunn came to New Zealand to head Queen Mary Hospital at Hanmer in 1993 and headhunted Claunch to run a counsellor-training scheme. The relationship between the former friends deteriorated when Queen Mary’s board chairman, businessman John Beattie, tried to introduce a business model to the then-privatised, financially struggling hospital and identified Claunch as the man who could introduce the changes Bunn wasn’t willing to make. Bunn accuses Claunch and Beattie of secretly conspiring to oust him.

A group of alcohol and drug workers who felt ill-treated by Claunch invented a new word for the experience. “We said we’d been Claunched”

Says Bunn: “I confronted Tom and basically said something was happening behind our backs and he denied it forcefully. Two days later, I got the call from John Beattie saying he was going to put Tom in over me. That’s when I blew my top and said, ‘Absolutely no bloody way.’ For a guy to do that behind my back…Integrity and loyalty are of great value to me. I was sabotaged.’’

In a deal to go quietly, Bunn started up a service at Queen Mary to audit and evaluate company employee assistance programmes. He returned to the US in 2006.

He says that over a dinner in Melbourne in the 1990s, a group of alcohol and drug workers who felt ill-treated by Claunch invented a new word for the experience. “We said we’d been Claunched. And they agreed I’d been Claunched worst of any of them.’’

Bunn says that when he was at Hanmer, Claunch rode a Harley-Davidson and drove a Corvette. He was driven by ambition, says Bunn; the need to be top dog. Despite that, says Bunn, he still liked him and had let go of his resentment. “I have a vision in my mind when Christ went to the temple and found the money merchants. If Tom had been with them he would have said, ‘Christ, let’s see if we can cut a deal.’’’

Claunch says Bunn was the only person in New Zealand who he thought knew more about addiction treatment than he did. “I have great respect and admiration for him. John and the board appointed me CEO instead of Jere and he was rightfully offended. In retrospect, I was disloyal to a good friend and wrong. I regret the whole issue and thought that I had made amends to Jere long ago.’’

Another who feels Claunched is George Thompson, the former director of Warburton Hospital in Victoria, which specialised in drug and alcohol treatment. “He tried to get rid of me,’’ says Thompson. He says Claunch, whom he describes as “big, bold and brassy’’, wrote to the chairman of the Warburton board suggesting Claunch replace him.

Thompson says Claunch trained him at Edinburgh in 1990 and he brought him to Australia three years later to train staff there. “It was the worst mistake I ever made in my life.’’

Thompson says he managed to get Claunch out of Warburton, but the resentment remains. “My only hope is that he falls off his perch.” Claunch is “overpowering”, he says. “In this business you work with people who are damaged emotionally, and not only have you got to be squeaky clean, you have to be seen to be squeaky clean.’’

Claunch describes Thompson as a “nice young man’’ but acknowledges he wrote to hospital management suggesting they “terminate George for cause and I stand by my consulting recommendation at that time’’. He says he did not have designs on Thompson’s job “in a small 15-bed unit in a Seventh-day Adventist hospital in an obscure Australian village’’.

Thompson and Bunn both question the ethics of Claunch’s marriage to June Venter, and Bunn also raises issues with the fact that Guy Smith was a former patient of Claunch’s when the pair set up Capri.

Claunch says he had no “fiduciary relationship’’ with Smith. Bunn says because he lived in Smith’s property, the payment was “in kind’’.

Like her husband, the new Mrs Claunch is mystified and hurt by all the fuss their relationship caused at Capri. “It was unbelievably upsetting.’’ She says after questions were first raised by Caroline Williams in February last year, they temporarily broke up. “I didn’t realise at that stage that Tom was so serious. He said he’d probably have to make a big decision in his life and I said, ‘Before you go any further, this is your work, this is your passion, people need you and there are lives to be saved and if that has to be, we just cannot see each other.’ But I was devastated. I talked to my family and said, ‘It’s crazy, what are we doing wrong?’”

She says that when she was first admitted to Capri nine years ago, she hardly saw Claunch, and although she attended his motivation sessions during her two weeks in therapy in September 2007 after a relapse, “He wasn’t my counsellor’’. She says despite the fact he was then clinical director of Capri, he was not in a position of power over her.

The pair met outside Capri at Elim Church, where both worshipped, and began going out early last year, about three months after Venter left Capri. Claunch asked her to marry him in November and the pair wed in two ceremonies — one in Alabama in December, the other at Elim in January.

It is not the first time Claunch has had a relationship with a former patient. In 2003, a Capri client alleged that a friend of hers, another Capri client, was dating Claunch. The woman herself had not wanted to complain and the friend’s complaint to the Health and Disability Commissioner was not taken further.

Claunch says that although he did have a relationship with the former client, it did not start until she had been “clean and sober’’ for two years. He says “the whole affair was fully open’’ but their brief relationship was destroyed by the “major flap’’ the friend made.

His offer to resign from Capri last year over his second relationship did not mean he acknowledged any impropriety. “I’d decided June was more important to me than this little job here, but the board decided that was not necessary.’’

As we speak in Claunch’s lounge, a visitor arrives. A middle-aged woman shuffles into the room. She appears barely able to utter a syllable. If she is not dying of the drink, it’s clear she has been at least very badly injured. Tom Claunch puts a welcoming arm around her shoulder and walks her into his office. The woman’s daughter had begged for his help the night before and Claunch agreed to try. Even his critics will agree he has a helping heart.

There is philosophical antagonism in the public service against an elitist provider like Capri, despite the fact it takes no money from the public purse. Though the abstinence-based programme it offers is solidly based, there is concern some staff do not belong to a professional counselling body and are therefore not bound by a code of ethics. Since taking over as director, however, Dale Smith, a registered social worker and member of the Association of Social Workers, says he wants counselling staff to join the Drug and Alcohol Practitioners’ Association, something Claunch did not feel was necessary.

Quiet, bespectacled Smith is Claunch’s opposite in every way. He shuns publicity. (After initially agreeing to be interviewed for this report, he cancelled our meeting at short notice and said he would take only written questions.) With Smith at the helm, you can expect Capri to slip from the headlines. A rehab counsellor at Rotorua’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital for more than three years before he began at Capri, Dale Smith says he has “an ongoing project this year to review our policies and procedures and ensure our staff follow these’’.

He says he was in an uncomfortable position conducting the investigation into the relationship between Claunch, his boss and mentor, and Venter, a client, and he and the board sought legal advice as well as advice from the office of the Health and Disability Commissioner.

After concluding Claunch’s relationship with Venter was not ethical, Smith directed him to review acceptable clinical practice, had the Capri board develop a policy on staff relationships with clients so future breaches did not occur, and instructed all clinical staff to attend monthly ethics sessions.

Perhaps the biggest question of all is “Does Capri work?’’ Even Capri doesn’t really know for sure and its competitors say they don’t know enough about what it does to have an opinion. Dale Smith refuses to divulge their “informal’’ results because “We have competitors.” Claunch believes the outcomes compare favourably with the best international centres, which claim long-term recovery rates of around 60-70 per cent.

Claunch doesn’t particularly care about his own popularity, or his critics. “I am either an unrepentant Southern gentleman or a male shogunist [sic] pig. I do not stand on unnecessary political correctness.’’

He is bullish about Capri and the “unfounded criticism’’ of rivals. “I do not think we have any competitors, as that would imply some equality.’’

Yes, he says, he talked about Millie Holmes; yes, he used “sexist’’ language. “The truth of what I strongly and unashamedly pronounced may have helped some young recovering people avoid what happened to Millie. As a father and grandfather of ‘gorgeous and beautiful’ girls, anything I can do to maybe help some young women avoid these really degrading and abusive consequences will be worth any heat I might receive.

“Everything I have done in over 35 years in the field was motivated by wanting to help others as I was helped. Perhaps I have been over-zealous or too intense at times. However, I bet you can find far more people who are grateful at being Claunched than those who regret it.’’

Editor’s Note: Tom Claunch died in March 2013.

A week of Capri

8.30am: Morning meditation. In a 45-minute session led by Claunch, clients read books from addict fellowships — there’s a fellowship for almost every kind of addiction, Alcoholics, Gamblers, Overeaters, Narcotics — even Emotions. The clients choose and discuss an edifying “soundbite’’ or uplifting quote that they’ve gleaned from their reading.

9.30: Life planning. Clients discuss what they’ve written the night before in their “black book’’ — how they felt, which “step’’ they’re working on and why, what they learned about themselves, and their goals for the day. Their daily recordings help them chart their recovery.

11.15: Recovery education. Videos or tapes are played or Claunch will give a lecture based on what clients say they want to learn about.

Noon: A meal prepared on the premises by a chef, who’s also in recovery, which Claunch says is “as good as anything you’ll get in Newmarket or Ponsonby’’.

12.45pm: Dale or Michelle Smith runs an hour-long small-group therapy session, where the clients share feedback and feelings.

2-4: Clients have one-on-one counselling three days a week. Those not in counselling are encouraged to exercise or take art or music therapy.

4-5: Study group.

5.30: Dinner.

On Monday nights, clients attend Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings, which they are strongly encouraged to continue when they leave. Wednesdays are family education nights, and on Thursday afternoons there are “community outings’’ to Kelly Tarlton’s, the museum or fishing. A barbecue and 12-step study group on Thursdays precedes a “sober fun’’ night out bowling. Dinner on Friday nights is a pizza party, and there’s a roast on Sundays.

Consultant psychiatrist Greig McCormick sees clients who need him on Tuesdays.

Morning meditation sessions are also held at weekends, but families can visit in the afternoons.

On Sundays, clients are encouraged to go to church.