Sep 4, 2024 Society

On a November afternoon in 1975, Joe Hawke was motoring along the Waitematā in his little boat. There was a big hui coming to town, a reunion for land marchers who had passed through on their way to Wellington a couple of months earlier, led by a famous and fearless kuia from the north, Whina Cooper. It’s customary in Māoridom to manaaki a visiting delegation and feed them well. The chiefs who had gathered in Waitangi in 1840 nearly stormed off when the British didn’t feed them the night before the Treaty was signed. The hapū of the central Auckland area, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, wasn’t going to let that happen on this occasion.

When the fishery officers pulled up beside Hawke’s boat, they peered in and saw a mighty haul of shellfish, far more than the 40 pāua allowed between the four on board. “They wanted to know whether I had a permit,” Hawke later recalled. “I said it was hanging on my wall: a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi.” Ngāti Whātua had been fishing the abundant waters of Auckland’s harbour and gulf for generations, from well before the Europeans, their governments and their fishery officers had arrived. Ngāti Whātua had never asked for a permit, because they had never given up their customary rights to gather and fish for hui and tangi. Indeed, even the dodgy English version of the Treaty explicitly protects Māori fishing rights. For Hawke, the encounter was just the latest slight against his people.

Ngāti Whātua had gifted what is now Auckland’s central city in 1840, its people establishing themselves across the bay at Ōrākei, presuming the Crown would honour its promise of a reservation. Instead, the Crown immediately went about stripping them of the rest of their land, using underhand purchases, Native Land Court judgments and other schemes to seize more and more acres. They’d been stripped of their harbour, too; reshaped and polluted by the mercantile city, the feeding grounds withered away. By the time Joe Hawke was born, in 1940, all that was left of Ngāti Whātua’s land was a small papakāinga at Ōkahu Bay, the fate of which would set his life’s path. When Hawke was 12, the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth paid a visit and the government wanted to take her for a ride around Tāmaki Drive’s picturesque bays. But there was a so-called “dreadful eyesore” along the way: the Māori village at Ōkahu Bay. To clear it up, the authorities labelled Ngāti Whātua squatters and moved to demolish the houses and marae before torching the rubble. A young Joe Hawke was there, watching the flames flicker and the smoke billow into the air. His people were then evicted, scattered across the city, landless on their own land.

That history and Hawke’s assertion of customary rights didn’t hold much sway over the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and Hawke was detained and brought before the courts, where he was convicted and discharged. Outraged, he hunted for a way to fight back. He had read in the paper that Parliament had recently passed a new law, the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, which had created a new semi-judicial body known as the Waitangi Tribunal. So he filed a claim. It was stamped with a case number: WAI 1.

Two years later, Hawke and about 50 whānau made their way into town and gathered in the ballroom of the Intercontinental Hotel, decorated with plush velvet seats, crystal chandeliers and oil paintings in extravagant frames. In an awkward scene, the first head of the Waitangi Tribunal, chief judge of the Maori Land Court Kenneth Gillanders Scott, sat at the front of the ballroom with a Tribunal member on each side of him. “It was simply off the wall to have Maori kaupapa in a situation like Buckingham Palace,” Hawke told a New Zealand Herald reporter in 2000. “We saw the futility of it and couldn’t stop laughing.” The laughs turned to bemusement when Hawke stood to present his case. Gillanders Scott told him he couldn’t do that because he wasn’t a lawyer. He didn’t need to be a lawyer to speak for his people, Hawke argued, but the Tribunal chairman wouldn’t relent. A lawyer was eventually found, but then Hawke would speak only in Māori, forcing the judge to wait while another Tribunal member, Graham Latimer, translated. It was an inauspicious start for the new commission of inquiry.

The Waitangi Tribunal was the great gamble of MP for Northern Maori and Minister of Maori Affairs Matiu Rata — an attempt to give effect to the deafening calls for the Treaty to be honoured. Amid a new wave of Māori protest, with its land marches, sit-ins, petitions and picketing, there was growing anger at how the pact that formed this nation had been disregarded by one side, as the Crown and successive New Zealand governments pursued policies of invasion and assimilation that left Māori all but landless, languageless, cultureless and impoverished. Since 1840, iwi and hapū had petitioned the government, taken legal action and called repeatedly for the Treaty to be honoured, only to be ignored at every turn. By the 1970s, polite appeal was turning ferocious as frustrations grew, moving from the select committees to the streets.

Rata, a quietly spoken man, had been born in Te Hāpua, the country’s northernmost settlement, in 1934. His father, Āta, died in a logging accident 10 years later, leaving his wife, Mereana, widowed with four children. Confronted by the choice of staying in the north or finding work, Mereana relocated to Auckland — part of the great urban drift — where she took up a job as a cleaner, the Ratas sharing a ramshackle house in Freemans Bay with 11 other families. It was a life of abject poverty. “Politics was not academic for us,” Rata would say, “it was very real.” He was 12 when he started work as a farm labourer and later a merchant seaman, joined the Labour Party during the waterfront dispute of 1951, and was working as a spray painter and union organiser for the railway workshops when, in 1963, the MP for Northern Maori, Tapihana Paikea, died. Shoulder tapped to run for Parliament, Rata won the byelection, aged 28. After the Third Labour Government was swept into power in 1972 on a surge of popular support for Norman ‘Big Norm’ Kirk, Rata became a minister.

Rata’s 1975 law was a hard-fought compromise that pleased few and did little to placate the protesters. But it was also subtly radical in a way few saw coming. For the first time, Te Tiriti was enshrined in legislation, and over the next 50 years it would force something of a reckoning, with far-reaching consequences for Crown–Māori relations, the recognition of tangata whenua, and how the law, courts and government operate. Most significantly, it made New Zealand’s history known, breaking the stubborn myth that this country was — somehow — founded peacefully, and still had the best race relations in the world. “To the Māori people, [the Treaty] is a charter that should protect their rights,” Rata told Parliament on introducing the Bill. “[It] is primarily aimed at satisfying that honour. It will also give physical and lawful sustenance to the long-held view that the spirit of the Treaty more than warrants our country’s continued support.” The Treaty was not a historical relic but a living instrument. It was a constitution.

Rata had originally wanted nothing short of the full ratification of Te Tiriti, making its terms enforceable through the courts, but his Labour Party colleagues wouldn’t have a bar of it. He then proposed a non-binding commission of inquiry to investigate both historical and contemporary claims, for both central and local government. But Cabinet didn’t like this either, sending him back to the drawing board. What finally emerged was a sort of rolling commission of inquiry where anyone of Māori descent could file a claim, no matter their role or status, if they believed the government of the day had breached the Treaty, either through law, policy, act or omission. With a judge at its head, and backed by a panel of Māori and Pākehā experts, the Tribunal would then decide whether to accept the claim. If it did, what followed was a long process of inquiries, interviews and investigations, involving written reports and oral hearings. The Tribunal was authorised to determine the Treaty’s meaning and effect, and compile its findings and recommendations into often-lengthy reports, sometimes over several volumes. Disappointingly for Rata, though, that was as far as its power went: none of its work would be legally binding on the Crown. But as an inquiry instead of a court, the Tribunal was also given much greater flexibility in what it investigated and how it went about doing so. It was the first judicial body to incorporate elements of tikanga and mātauranga — completely foreign to Pākehā courts at the time — as well as iwi and hapū oral histories. It also provided a legal process for the Crown’s crimes to be publicly aired and investigated.

“I think [New Zealand] was on a path where there would have been significant civil disruption if not for the Waitangi Tribunal,” says Carwyn Jones, head lecturer for the Māori laws programme at Te Wānanga o Raukawa. “Now you have a situation where all the political parties have the position of supporting the settlement of historical claims and recognising the harm that was done and the need to address those harms. That certainly wasn’t the case before the Waitangi Tribunal.”

Matiu Rata, 1972 by Robin Morrison

The new commission of inquiry had a slow start, investigating just 14 claims in its first decade. But these claims achieved small victories for several hapū. In Taranaki, the people of Motunui hold waiata that speak of the abundance of kaimoana along the reefs they’d fished for generations. By 1980, those lyrics were starting to ring hollow: the moana was ailing. All along the coast, towns, boroughs, meatworks and methanol plants had concrete pipes that pumped their waste and sewage straight into the sea. In the space of a couple of generations, the Te Ātiawa food basket had been destroyed. Elders spoke of people diving into the water and emerging with a rash, of surfers who watched toilet paper float by as they bobbed in the waves. Then, in 1981, Syngas was given permission to build a pipe to shoot the waste from its chemical plant straight on to the Motunui reef. No one had thought to ask the people of Te Ātiawa, and they’d had enough. The pollution was killing their way of life, they told the Tribunal, and had nullified their right to the undisturbed possession of their fisheries as promised by the Treaty. The Tribunal agreed, and after it released its report in 1983, the Syngas pipe permission was revoked. The New Plymouth City Council also renewed its entire sewerage scheme. But these were small-scale wins, and did little to address the overarching injustice Māori felt or placate the demands of the new generation of Māori activists.

In 1978, the Tribunal came back with its ruling on Joe Hawke’s WAI 1 claim: ultimately, the case was thrown out on a technicality because he had not been “prejudicially affected”. It didn’t matter much — Hawke was now otherwise preoccupied. On the rolling meadow above Ōkahu Bay, he had set up a ramshackle encampment overlooking the great Waitematā. It was prime property, and also stolen land.

Takaparawhau, or Bastion Point, had been taken over for defence purposes during the Russian scare of the late 19th century, but the Crown didn’t give it back when the Russians didn’t show. In 1977, the Robert Muldoon-led National government tried to sell the land for a subdivision. “It was a rather grandiose idea for rich people,” Hawke recalled in 2018. “Ngāti Whātua was nowhere in the scheme of things.” So he swung into action, occupying the land and refusing to leave for 506 days. Bastion Point became the site of one of the country’s most famous protests, and supporters joined from across the country as a makeshift village of tents, shacks, kitchens, gardens and a marae named Arohanui grew. Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei were landless, Hawke said, and had nothing to lose by holding out. That determination would be sorely tested when, on 25 May 1978, the coercive arm of the state swung into action against Ngāti Whātua once more. Six hundred police officers with dark trenchcoats and white helmets surrounded the encampment and marched in, wielding their batons. A digger dropped its arm through the roof of Arohanui. It was Ōkahu Bay repeated — 222 people were arrested, including Hawke, who called the eviction a “monstrous, barbaric, idiotic act”.

He filed another claim to the Tribunal, seeking the return of the land at Takaparawhau. As luck would have it, by the time hearings got under way in 1984, there had been a change of government. This new government was looking to pass a law, drafted by the attorney-general and Minister of Justice, Geoffrey Palmer, over what the Waitangi Tribunal could do. Instead of examining just present-day claims, it would be allowed to inquire into Treaty breaches dating right back to the signing in 1840. “I never got as much mail opposing anything as when we did that,” Palmer told RNZ in 2017. “People hated the idea; there was a lot of racism. They just felt that Māori shouldn’t have these things… The public doesn’t really understand properly; they didn’t understand the settler government injustices that were inflicted on Māori.”

Debate over the proposed changes was fierce. A National Party MP described it as the “most dangerous Bill that has been introduced”; Palmer argued in return that New Zealand would collapse as a democracy if the government failed to address its past; and iwi and hapū watched keenly, ready to pounce. After the amendment act passed, in December 1985, there was finally an avenue to obtain legal recourse for over a century of injustices. It was like a pressure valve being released, Carwyn Jones says.

Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei revised their claim and this time, instead of the farcical scenes of the hotel ballroom, the Tribunal came to Ōrākei Marae, on the edge of Bastion Point, where Joe Hawke stood before them once more. “A lot of people, predominantly the younger people, did not know there was a tangata whenua resident in Auckland. We are reasserting our authority to be tangata whenua here,” he said. “I’d like [the Tribunal] to acknowledge the wounds of the tangata whenua. I’d like them to explain to us as tangata whenua how these injustices, the wounds that have been heaped upon our people, eventuated.”

Over a week of hearings, the Tribunal heard first-hand stories of what happened at Ōkahu Bay. The ultimate shock of the 1952 eviction proved too much for the kuia, Ani Pihema said, and several died in quick succession soon after. Tribunal members heard how the water ran off Tāmaki Drive and flooded the urupā whenever it rained, how the marae they were sitting in was built on land Ngāti Whātua didn’t own. Tōhunga Māori Marsden told the Tribunal that a tribe’s mana is derived from the whenua and tūrangawaewae. Without those two things, the mana of a people is diminished. It’s hard to have a place to stand when there’s nowhere to stand, a situation he described as a “humiliation”.

The resulting report found that the Crown had breached the Treaty when it failed to ensure a reservation, it failed again when it took the land at Ōrākei, and again when it evicted the people from Ōkahu Bay. The issue was about more than compensating for land loss, the Tribunal found — it was about re-establishing Ngāti Whātua on their ancestral land with a secure economic base. In a letter accompanying the report, the Tribunal wrote: “The story of Orakei gives sharp relief to the same problems that beset other people in other places and covers national policy from 1840 to the present day. For Orakei is a microcosm of the country.” The government was forced to relent, returning Bastion Point along with $3 million in compensation.

“In this report we have tried to balance a mass of official opinions and records with the story Ngāti Whātua know,” the Tribunal said. “To capture the latter we spent time with the people, shared their meals, listened to them and discussed with them at their marae.” This was a groundbreaking approach, says Carwyn Jones, as it allowed a comfortable space for Māori to share their histories in a way that upholds tikanga. “It means that when you’re sitting in a wharenui which has carvings of the ancestors that people are talking about, and the stories of those ancestors that people are talking about, that evidence is heard very differently and received very differently.”

Holding the hearings on the marae, instead of a gaudy ballroom or a sterile courtroom, celebrated the kaumātua whose knowledge filled the claims. A witness could stand, surrounded by their people, and launch into a free-flowing kōrero, recounting the origins of their people, the relationships of their tribe and the deeds of their ancestors. Not in a legal manner, but in the manner of a tupuna. Significantly, the move also brought the judges and the Crown’s bureaucrats before the communities who carried the grievance, to hear powerful testimony of the wrongs and their effects on whānau. “I heard some of the most amazingly painful and difficult and wonderful stories,” Justice Joe Williams, a former Tribunal chair who now sits on the Supreme Court, told broadcaster Moana Maniapoto in 2021. “Although iwi focused on what had been lost, the claims themselves were held on marae and ended up always being a celebration of survival. Truth and reconciliation in Aotearoa was never self-pitying. It was self-righteous and self-empowering.”

To read a Tribunal report is to open a window to the inglorious foundations this country is built on. Thousands upon thousands of pages of research from decades of inquiries form a detailed catalogue of invasion, atrocity, deception, misdeeds and bloodshed that stretches from the Far North to the Deep South. Margaret Mutu, a professor of Māori studies at the University of Auckland and a claimant for Ngāti Kahu, says the Tribunal’s most important work is bringing the truths held by iwi and hapū, but often ignored by others, out of the dark. “The facts that were uncovered, once they were uncovered, you couldn’t hide them,” she told me. “It was a huge shock for Pākehā New Zealand, because in the process of colonisation and dispossession, there had been a deliberate mythology developed amongst the Pākehā community in this country that all they had done was brought benefits and good things, and any Māori who complained was not the norm.” But now that their breaches were in the open, the Crown could no longer look the other way. In the 1990s, the National government under Jim Bolger and the first Minister of Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations, Doug Graham, started a process of negotiating settlements with iwi around the country. It was a tortured and protracted process that led, ultimately, to most iwi settling for compensation amounting to less than 2% of the value of what was taken.

As soon as the historical floodgates were opened in 1985, whānau filed hundreds of claims, swamping the Tribunal with work. In order to cope, it merged many of them into what became known as district inquiries — such as Te Rohe Pōtae for the King Country, or Te Paparahi o te Raki for the tribes of central Northland. For nearly 40 years, the Tribunal has been holding hearings on shaky trestle tables, under the gaze of poupou, in small marae and community centres up and down the country, in a series of inquiries that have often been slow, painful, expensive and intensive for hapū who have few resources. To read a Tribunal report is to gain an insight into the exhausting, multi-generational nature of a claim. It’s rare that the person who submits a claim on behalf of a tribe lives to see the report published. The first pages always form something of an ‘in memoriam’.

Following the death of Norman Kirk and the Labour Party’s loss at the next election, Waitangi Tribunal architect Matiu Rata was dumped as Māori affairs spokesperson, in 1975, and then demoted to the backbenches, in 1979. He quit the Labour Party in response, going on to form the new party Mana Motuhake, but failed in a bid for re-election in the subsequent byelection. His days as an MP over, Rata went home to Te Hāpua, where his people were looking to bring their own cases to the Tribunal. Who better to help lead these claims than the man who made it all possible? The hapū of the very tip of the North Island are surrounded by the sea; their long sliver of land has the ferocious waves of the Tasman Sea on one side, the calm blue of the Pacific on the other, and an impressive duel of oceans coming together at the top. The Muriwhenua people had intricate traditions tied to their fisheries. They could read the waves, tides, currents and clouds, and would sail as far afield as the Kermadec Islands using techniques passed down through generations. When Europeans arrived, the people of Muriwhenua began making handsome sums from their fishing operations. In 1840, 61 of the area’s chiefs signed the Treaty, with its explicit guarantee of sovereignty and undisturbed access to fisheries. By the end of the 19th century, however, they had been cut out, explicitly banned from the commercial harvesting of kaimoana. Fish stocks were plundered by commercial fleets throughout the 20th century until, in the 1980s, the government proposed a new quota system that excluded Māori. It was an obvious breach of the Treaty, so Muriwhenua took the problem to the Tribunal, and the government was forced in the late 1980s and early 1990s to set aside a portion of the new quota for Māori fisheries.

Then it was time to address the issue of land loss. The Tribunal, in 1997, concluded that “with nearly all their usable land gone, Muriwhenua Māori were reduced to penury, powerlessness, and, eventually, state dependence”. Fifteen years later, one of Rata’s hapū, Te Aupōuri, would reach a settlement, agreeing to the return of land including parts of Cape Rēinga and Ninety Mile Beach, $21 million and, significantly, an agreed historical account and Crown apology.

Matiu Rata would never see the fruits of this labour. Just a few months after the Muriwhenua report was released, he was driving home after a meeting in Auckland. As his Nissan wound its way along State Highway 1, just outside the village of Te Hana, a car coming the other way crossed the centre line and collided with him head on. He was rushed to hospital with critical injuries, but died eight days later on 25 July 1997. He was 63.

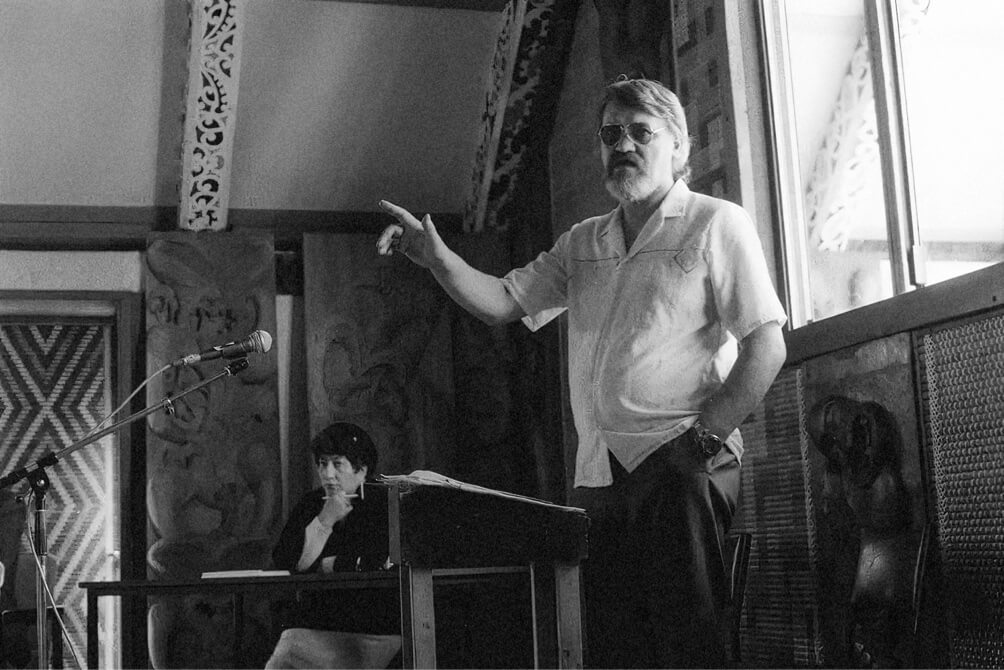

Joe Hawke speaking. Waitangi Tribunal, Ōrākei Marae, 1985 by Gil Hanly

In the early 1980s, the Department of Maori Affairs had set aside some cash for various groups to spend promoting te reo Māori “as they saw fit”. One of them was Wellington-based Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo, and its founder, Huirangi Waikerepuru, decided to spend the money by taking the Crown to the Waitangi Tribunal. He wanted the Tribunal to recommend that Māori be made an official language, that a Māori language commission be established and that the government support Māori-language broadcasting and bilingual education. When hearings were held over four weeks in 1985 at Waiwhetū Marae in Lower Hutt, busloads of people travelled there from all over the country. The Tribunal heard from elders who had been struck for speaking te reo at school, and saw the language wither from their lives and communities. It heard from young activists fighting for language survival, who said access to their native language was a birthright. It heard how native schools were created in Māori communities, designed for assimilation, and how the language had been ignored by officialdom. The language was a taonga, protected by the Treaty, and without it, the Māori culture would die.

WAI 11, as it was known, was a groundbreaking claim, the first that was not related to natural resources or one specific iwi or hapū. Instead, it was a claim for all Māori against every branch of the Crown. The destruction of te reo had been enabled by every lever of government, claimants argued, from the education department that discouraged it, to the state-owned radio that refused to broadcast it, to the Parliament that refused to legislate for its protection. This combined effect had seen the language of Aotearoa nudged to near extinction, with only 5% of Māori children able to speak it. The Tribunal, in its 1986 report, said te reo Māori was indeed a taonga. The Crown had signed a treaty and, therefore, had an obligation of “active protection”. The government was embarrassed into action, making te reo Māori an official language, establishing a language commission and funding Māori broadcasting a year later.

The thematic examination of issues that span the entire government, and their effects for all Māori, can be an ambitious exercise; such examinations have kept the Tribunal busy for lengthy periods of time. Known as kaupapa inquiries, these broad inquiries involve years of work and have, so far, looked into the inequities Māori face in the health system and education, the loss of control over intellectual property and mātauranga, and how Māori became one of the most imprisoned populations in the world. As the historical inquiries wind up — the Fifth Labour Government in 2006 set a deadline of 2008 for lodging past claims — the kaupapa inquiries are now in the 2020s becoming the Tribunal’s predominant focus, a return to the remit it was given in 1975.

The Waitangi Tribunal has, over nearly 50 years, become the first port of call for concerned Māori whenever the government announces a policy or an action that is likely to undermine the Treaty’s promises. During the Rogernomics blitz of the 1980s, when the government was zealously selling off state assets and putting others into the control of profit-seeking state-owned enterprises, the Maori Council rushed to the Tribunal to delay any land transfers. Many of the forestry plantations, power stations and other infrastructure the government was trying to transfer were built on land that was taken by nefarious means. If it was sold, it would become private land, taking it beyond the powers of the Tribunal and off the table for settlements. The Tribunal’s findings, and a subsequent challenge that went as far as the Court of Appeal, effectively enshrined the principles of the Treaty as part of the basic common law of Aotearoa. As recently as May this year, the Court of Appeal held that the Waitangi Tribunal “has a role of constitutional importance”, with the Treaty today far from a “simple nullity” — as Chief Justice James Prendergast had notoriously dismissed it in 1877 — but a “major source of this country’s constitutional makeup”. Indeed, many of the Tribunal’s findings, interpretations and recommendations have worked their way into common law or been folded into legislation. More than a century after being dismissed as a nullity, the Treaty is finally being acknowledged as a constitutional document.

But that doesn’t necessarily make it loved, especially among Pākehā. “The Waitangi Tribunal would certainly win no popularity contest amongst the wider community,” Joe Williams once wrote. A former chair, Justice Eddie Durie, had to delist his phone number and address, so intense was the torrent of hate mail. During the 1990s, when the settlement process was beginning, claimants would find bullets in their letterboxes; fear merchants drummed up hysteria that the powerless Tribunal was a front for a Māori takeover. “When you have a commission of inquiry — which is a judicial body — issuing reports which talk about these unspeakable atrocities, the whole country was stunned that the Tribunal would, one, make these findings and, two, dare to articulate them,” Margaret Mutu says. “So there was actually quite a backlash. They did not want to hear any more, so they started attacking the Tribunal, they wanted it abolished, and they wanted to stop the talk.”

Though the Tribunal remains one of the key avenues for addressing Māori grievances, it isn’t universally adored by Māori either. Claimants have long complained of its cumbersome, complicated and under-resourced processes. Small whānau, sustained only by volunteers and generational self-belief, are often pitted against government legal departments fronted by king’s counsel. Taking a claim on behalf of a whānau often exacts an immense toll, with many people having dedicated their entire lives towards having their grievances heard and settled.

Then there’s this: the Waitangi Tribunal is still a Crown institution, fronted by judges who have sworn an allegiance to a monarch. For Māori to have a commission of inquiry that is only able to issue recommendations that can be ignored by the Crown is hardly the partnership, equity and tino rangatiratanga promised by the Treaty. It’s “another, browner, part of the coloniser’s legal system”, said longtime Treaty lawyer and activist Annette Sykes in a forceful lecture in 2020. “Once the courts got hold of Te Tiriti they went on a frolic of their own, developing Treaty principles that simply affirmed Crown sovereignty and showed contempt for tino rangatiratanga.”

Eddie Durie speaking. Waitangi Tribunal, Ōrākei Marae, 1985 by Gil Hanly

On 10 October next year, the Waitangi Tribunal will be 50 years old. Nothing can stay the same for half a century, and as Carwyn Jones says, no doubt some things should be changed or reviewed. A healthy discussion about its role in the 21st century would probably have merit. But, he adds that the Tribunal is likely to remain relevant for some time yet. “While the Crown is still continuing to take actions which are in breach of the Treaty and are prejudicial to Māori, I think the Tribunal still has a very important role in pointing those out.”

In the first five months of the year, the Tribunal agreed to hear four urgent inquiries alleging that the coalition government breached the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. The threshold for urgent inquiries is normally high. Yet the decisions in question — abolishing Te Aka Whai Ora, mandating referendums to establish Maori wards in local government, promoting the use of English over te reo Māori in the public service, and removing references to the Treaty in the Oranga Tamariki Act — had unusually acute consequences. Now, the government is signalling it will proceed with a review of the Tribunal, a move that could be read as potentially retributive.

Today, on the sunbathed hill of Takaparawhau can be found the grave of Joseph Parata Hawke, who died in 2022, aged 82. He was farewelled with a massive tangi at Ōrākei Marae, attended by the deputy prime minister of the time, Grant Robertson. “When we come to this land, we come humbled,” Robertson said. Hawke was laid to rest on the land he fought so hard to have returned, looking across the glistening harbour, busy with sailboats, ferries and cargo ships, where he had had that momentous run-in with a fishery officer 50 years earlier.

–

With thanks to Gil Hanly and the estate of

Robin Morrison.

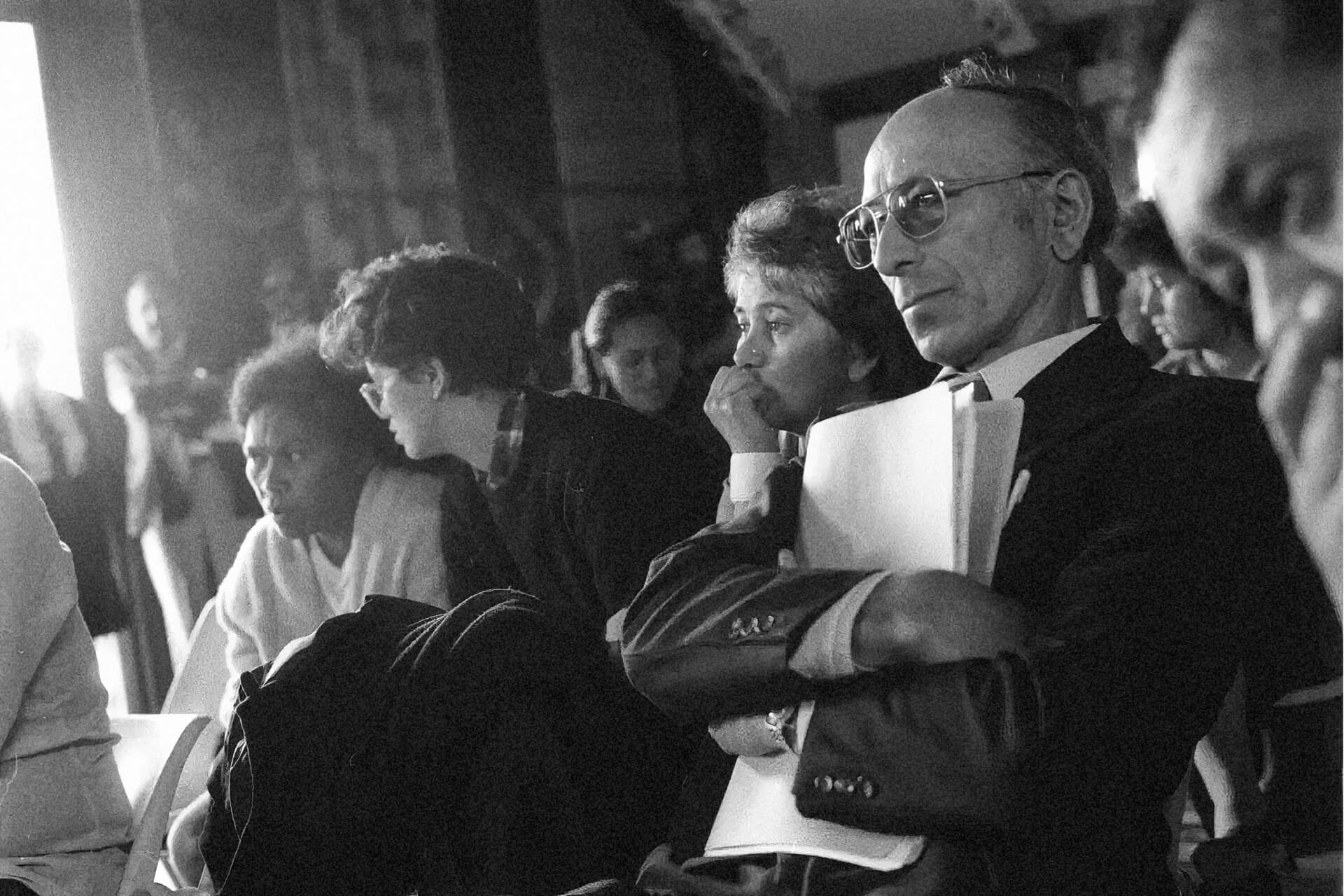

Lead image: Ranginui Walker and group listening.

Waitangi Tribunal, Ōrākei Marae, 1985 by Gil Hanly

This story was published in Metro N°443.

Available here.

This story was made possible by

NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund