Jan 22, 2015 Urban design

Not so long ago, urban design badly lost its way in Auckland. Has it recovered? Simon Wilson reports.

This story first appeared in Metro, April 2009. Photographs by Simon Young.

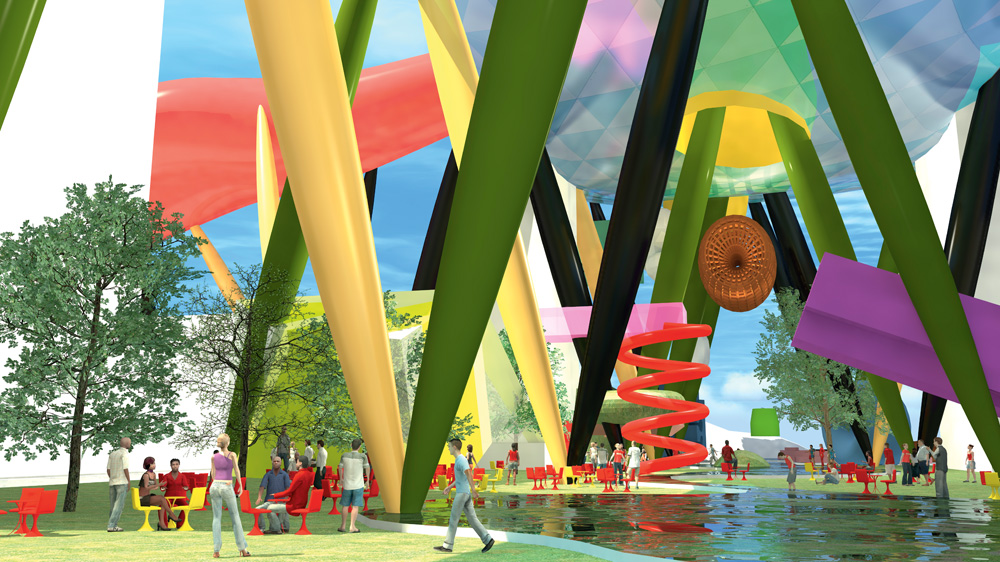

This is the Britomart square, though not as we will ever see it. In this concept plan by leading British architect Will Alsop and the Auckland firm Ignite, the square is dominated by coloured stalks supporting a building so high off the ground it offers shade but does not obscure the views from the other occupants of the square. The ground is landscaped, with grass, trees and running water.

The high building, within the diamond-patterned membrane, contains offices and a department store. On its roof, open to the public, there is recreation: eating and drinking, a cantilevered lap pool and more. Rising from the roof, a slender apartment tower. Two shapes thrust from the heart of the building out over Quay St, containing a five-star hotel and… a library!

How many rules in the District Plan does this break? Jeremy Whelan of Ignite reckons it’s 90 per cent compliant, but he is clearly an optimist.

That’s not the question, however, because the plan will not be built: Alsop and Ignite produced it as an exercise in creative thinking. Better to ask: why is there so little evidence of inspired creativity in the work of our own architects, developers and planners? Why is Auckland urban design so damn mediocre?

Fear not, there is justice in the world. The view from the Civic Building — the tower block near the bottom of Greys Ave that houses Auckland City councillors and town planners — makes Auckland look like the worst of East Berlin. Every day, they get to look out at the backs of the ugly apartment blocks on Hobson and Nelson Sts, unable to see the harbour bridge or the greenery of Freemans Bay, and getting just a peek of the lovely harbour.

In February, Cr Aaron Bhatnagar showed me this view from the “councillors’ lounge” on the 14th floor, itself a fairly ghastly wasteland of stranded couches. His party, Citizens & Ratepayers, allowed — no, let’s be accurate: it strenuously encouraged — this pillaging of the urban environment, and he is not proud of it. Chair of the city development committee, he showed me this view because he wanted me to know he understands. Things have changed. The bad old days have gone.

Indeed, in that same week the Auckland City Council finally and unanimously voted through changes to the District Plan that will, as Bhatnagar told the council, “help put an end to the chicken-coop apartments”.

It’s a new day.

No, wait. What? “Help put an end?” What does that mean? Are the bad old days over or not?

“The new regulations should put an end to the bad old days,” he confesses later, “but developers are always looking for loopholes in the District Plan. You can’t say for sure what’s going to happen.”

Hmm. What about buildings that were approved under the old rules and have not yet been built? Is there more Stalinist architecture still in the system? “I’m not sure of the details. You’d have to ask John Duthie. He’s got a list.”

John Duthie says he doesn’t have a list. He’s the general manager of city development, the top dog in the planning department. He’s been top dog since 1989; his father once had the same role.

A compact man in baggy clothes, Duthie likes to talk with enthusiasm about the future of “our world-class city”. He also has a thorough command of rules and regulations and a bureaucrat’s vague way with some of the trickier issues. He says any sites where a building consent was applied for after the new rules were proposed “a couple of years ago” will have had to conform to both sets of rules. That’s how the system works. But consents are valid for five years, he adds, so yes, “There might be some on the books from four or five years ago,” that wouldn’t fit the new rules.

Might be? “I’m not aware of any.”

Will he be checking? “Yes, we’ll be going back to check.”

And what will the council do? “I would think we would want to talk to the developer.”

In Auckland, there’s a gap. On the one hand, the natural attractions and the magnificent early efforts of the city fathers; on the other, the paucity of the whole post-war built environment. This gap is so huge, everyone responsible should hang their heads in shame.

Later, we asked which sites in the CBD had consented projects that wouldn’t fit the new rules. Council officers indicated there were probably a handful, and then said they could not identify them. So what of Duthie’s assurance they would be talking to the developers concerned? Is that going to happen any time soon? Duthie did not respond to further queries.

Right in the middle of the view from the councillors’ lounge, on the corner of Cook and Hobson Sts, is an almost-vacant lot containing a heritage building from 1885, currently known by the name of its last tenant, Canvas City. The site is owned by Korean company Dae Ju Housing Developments, which has already gifted the city such monuments to the future as the Victoria Apartments opposite TVNZ.

Dae Ju wants to demolish Canvas City and build more apartments. The council says it wants to save the building. For heritage campaigners, the fate of this building is a litmus test for the council’s professed new-found commitment to Auckland’s urban design.

Is this important? Even if you’re happy sitting in your car and don’t want to hear about light rail; even if you don’t mind what buildings look like; even if you don’t want to eat your lunch on the waterfront or sit under a tree with a cup of coffee, you might still consider it this way: good urban design makes money. In all sorts of ways. When people don’t waste time getting around, they are more efficient. When buildings are spectacularly good, they become tourist attractions. When people like the city environment, they want to come and work here.

Urban design starts with cars. Or, one should say, with making it easy, cheap, safe and enjoyable to do without them — at least some of the time. When the roads aren’t clogged, the buildings and public spaces of a city start to breathe a new life.

But regardless of what happens with transport, there’s still an awful lot that can be done with the built environment. British architect Will Alsop put one of his astonishing buildings into Peckham, London, as the new library. He was told it had to attract 12,000 readers a month. Now it gets 36,000. He created an extraordinary box on stilts for a design school in Toronto, and there was a 300 per cent increase in student applications.

Good design can change the whole culture of a city.

The Shame of the City

In Auckland, there’s a gap. On the one hand, the natural attractions and the magnificent early efforts of the city fathers; on the other, the paucity of the whole post-war built environment. This gap is so huge, everyone responsible should hang their heads in shame.

With a few notable exceptions, the gap exists throughout the modern greater urban area. Although this article is primarily concerned with the downtown and waterfront precincts of Auckland City, the argument holds for the rest of the city and for the wider region.

How did this happen? There are so many reasons and most of them interlock: the market-oriented reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, the roads-focused planning of the 1950s and 1960s, the lack of money, the economic priorities of the port, the conservatism of retailers, the short-term goals of landlords, the lack of political leadership, the supremacy of private-property rights, the cowardice of officials, the complicated nature of Auckland governance, difficulties with the topography, mediocre architects, irresponsible developers, the dark desire of successive central Governments to keep Auckland weak. Even the very quality of the beaches and the bush: maybe we don’t really care about Auckland because we don’t need to. We can escape so easily into the beauty that is all around.

Aaron Bhatnagar says former C&R councillors from the 1990s tell him they now realise, “We missed the boat.”

We don’t use the word “vandalism” to describe this kind of thing, but isn’t that what it was?

That’s putting it mildly. In the laissez-faire planning culture that prevailed from the mid-1980s until early this century, a minimal regulatory environment was established in the belief that an unencumbered market would deliver good urban design. Developers were invited to “build what you can”, says Alex Swney, chief executive of the business lobby group Heart of the City. “The trough was lowered.”

Campaigners and some councillors fought the good fight, but victories were rare. Those chicken-coop apartment blocks sprang up in or near the city centre.

Streetscapes were blighted by buildings with carparks on the first few floors. Heritage buildings were given tacky additions or bulldozed altogether, some to be replaced with complexes — such as Chase Corporation’s MidCity multiplex — that were so shoddily made they started to fall apart almost as soon as they were finished. Some sites simply remained holes in the ground. We don’t use the word “vandalism” to describe this kind of thing, but isn’t that what it was?

Duthie claims the market delivered some good things, and cites the Chancery retail complex, the Britomart area, developments around the universities and “parts of the Viaduct”. But actually, he agrees, the market did not deliver Britomart or the university sector: at least in those places, laissez-faire planning was not allowed to prevail.

On and on it went. In the late nineties, Mayor Christine Fletcher introduced some quality goals to the planning process, but it wasn’t until developer Tony Gapes put up the Scene Apartments on Beach Rd that enough powerful people woke up.

The apartments are just big piles of little shoeboxes, although that wasn’t the worst of it. The first three floors are carparks, turning what should have been a lively piazza near the site designated for Vector Arena into a hideous pedestrian no-go zone.

Even that wasn’t the worst. Gapes blocked the view shafts of the harbour from the precinct around the law courts and the university. And that was too much.

It wasn’t until developer Tony Gapes put up the Scene Apartments on Beach Rd that enough powerful people woke up.

Tragically, this wasn’t even the plan. He wanted to put up taller apartment blocks that would preserve the views because they would be much skinnier, but because of the height would also require a dispensation to the District Plan. The council told him no: build what you’re allowed, they said, but we will not support you seeking a more creative solution for the site.

John Banks was mayor by then, and John Duthie was firmly in charge of planning.

Alex Swney says the same attitude prevails today: it’s very hard to get council support for changes to the District Plan, even where the outcome would demonstrably be improved urban design.

In 2003, Banks established an Urban Design Panel (UDP), jointly sponsored by the Property Council and the Institute of Architects. All big developments would now have to go through a consultative committee of urban design experts, with a membership drawn from the city’s architectural, development and business communities.

Banks’ successor, Dick Hubbard, went further, expanding the UDP, setting up a Mayoral Taskforce on Urban Design and creating a new position for an urban design champion — someone who would critique the council’s ongoing work, monitor applications for planning consent, initiate new proposals and, while answerable to John Duthie, inject a significantly higher quality of planning into Auckland City.

Enter the Superhero

Ludo Campbell-Reid, superhero, otherwise known as the council’s urban design manager, was headhunted from London, where he had been in charge of co-ordinating transport planning. He got off the plane for his job interview here in 2006 and told his wife they would need to find the station to get the train into town. That was the first shock.

The second came half an hour later, once his cab became stuck in traffic in suburban Epsom. There is no way, he decided, that this could be the best route into the city centre. So he picked a fight with the driver. “I accused him of taking the piss.”

He saw people sorting through great piles of rubbish on the side of the roads — it was inorganic collection time. Finally, he arrived in Queen St. “It was so upsetting. The signage was such a mess, there were broken kerbs, people kept tripping on the paving. It was like a Third World city.”

So he took the job. Something to do with the size of the challenge? “Yeah. Auckland could be successful for the thing it’s worst at. The built environment, you know? Even if it takes 30 years. I mean, it’s the renaissance of a city.”

Campbell-Reid is a stocky, bullet-headed man, an ex-Olympic rower, and he has a natural charm that makes him easy to like. He wears smart suits with an open collar, lives in Devonport, catches the ferry every morning and zips up Queen St on the footpaths — widened on his watch — on a scooter.

He likes mischievous ideas: “We should have placards on all the buildings with the phone numbers of the architects and the developers.” Then anyone could ring them up and tell them what they thought, like trucks that invite you to comment on the driving.

He’s proud of the nikau palms (“What other city in the world…?”), proud of all he’s been part of. The Queen St upgrade has tilted the balance in favour of pedestrians and increased foot traffic on weekdays by 31 per cent. He spiked the plans of the Britomart developers to change the height of their hotel tower after all the agreements were reached. He runs public lunchtime seminars with visiting speakers, holds big-idea briefings for councillors, and co-ordinates a staff of 15 spread through all the planning departments of the council.

Bhatnagar claims he is so influential that in days to come we will talk about the “pre-Ludo and post-Ludo eras”. He adds that he is “kind of fond of the guy”.

Will Alsop, who has worked with him in London, says, “I imagine that Ludo lies in bed at night with a vision.”

“Architects don’t do city buildings well. Even the good ones, they’re grounded in the bach, the mountains, the bush.”

Be that as it may, three years into the job, Ludo Campbell-Reid is not happy. Ask him a question — any question — and he can’t stop talking, one moment enthusing about what’s possible, the next lamenting the difficulties of the job, then praising his colleagues and ticking off all the good things they have done “incrementally”. During many discussions for this story, he almost always worked his way around to an abiding theme: the poor quality of architecture and development plans in Auckland.

“There’s so much crap. Look at the North Shore, all those beach suburbs full of lost opportunities. And in the city, architects don’t do city buildings well. Even the good ones, they’re grounded in the bach, the mountains, the bush. They’re great at the domestic. They don’t do urban.”

His email inbox is a long list of unopened messages, his diary is stuffed with meetings, and he has so much to do just to keep up: sign-off on every council capital expenditure proposal worth more than $200,000; oversee pretty much every building plan for the CBD and every consent application across the isthmus above the domestic scale. Ludo Campbell-Reid is trying to turn the unacceptable into the adequate, one consent application at a time.

He says he has good days and bad days. On some of the days we talked he seemed stuck in quicksand, talking and talking as though he was trying not to panic. What’s gone wrong?

Auckland is full of committees that care about urban design. There’s a CBD Board, a Committee for Auckland, an Infrastructure Council… In many ways, they jolly things along. But local government overall is a conflicted, seething mess, and because of this — and because of a lingering attraction to laissez-faire policies among the dominant C&R team — there is a lack of articulated strategic vision at Auckland City Council. There are also signs of a can’t-do, don’t-care culture. From the people in charge of big ideas to the street-level compliance officers, the planning and development functions of the city council can seem beset with inertia and disregard. Ludo Campbell-Reid may be well thought of, but even Batman couldn’t fix all that.

Alex Swney tells a story about a “high-profile international brand” that wanted to open a shop on Queen St. The only condition: they wanted the bus stop outside the doors moved. The council said no. Just along the road there was a bank that was very keen to have a bus stop outside its doors, because bus stops are well lit and always busy, so they make ATMs safer. The council still said no.

Retailers all over Auckland have stories like this. Restaurateurs can’t believe how picky the council officers are. One had to make small changes to the positioning of tables on the footpath, although the new “complying” arrangement made it harder for pedestrians to get past. Another had to wait a year for approval on minor issues, although they had taken over the premises from another operator. Shopkeepers get the impression the council doesn’t care if they set up or not.

I asked Aaron Bhatnagar about this and got a long pause. He knew what I was talking about. Eventually, he said they were working on staff training.

A culture of not being there to help beats down every-one’s standards. When I asked Campbell-Reid what would happen if Will Alsop’s Britomart Square proposal came across his desk, he dissembled. “The process of allowing something like that is very procedural… It could go to the Environment Court, it would take a long time… We would struggle with something like that.”

He did say, “But Auckland needs extraordinary buildings,” but he also said, “We can’t be as visionary as we like.” And he dissembled some more about fundamental rules, told me that 80 per cent of the proposals he sees are “average”, and added, “You spend your life saying no to so many bad ideas.”

I said I had expected him to say that if one of the top 10 architects in the world (which is how he views Alsop) walked into his office with a proposal, he would say, “Wow, I’m glad you’re here. How can we help?”

The next day he said, “If a top-10 architect came in? Of course we would be excited.”

Campbell-Reid knows the setup isn’t good enough because he’s worked with better. Alsop says back in London, his boss at the time, Mayor Ken Livingstone, “was genuinely interested in architecture. His attitude was to say, ‘Yes, that’s really great. Now how can we make it happen?’ Or else to tell you to fuck off.”

“Urban design is like a ball at the top of a hill. It’s teetering. It could roll either way, it could slip back or it could go unstoppably forward.”

The redevelopment of London over the last 20 years has followed a strategic plan. Fit within it, and they’ll actively help you; fail to meet its high aims, and they will block you. Wellington planning gets described in the same terms. It’s the antithesis of laissez-faire, and it’s what we need in Auckland.

Campbell-Reid says things are changing. A “Fairwinds” system now tries to identify good schemes at an early stage and help them through the approvals process. Another called “Streamline” will shortly be introduced to complement this. Both, however, rely on a “tick all the boxes” approach, rather than identifying inspired vision.

Rules. They’re important to stop things going wrong. They become a problem if you use them to prevent talent and creativity from flourishing.

Bhatnagar says urban design is getting better all the time. “The sum of things, they’re little things, but they will indisputably make Auckland a better city.”

Campbell-Reid reckons right now, “Urban design is like a ball at the top of a hill. It’s teetering. It could roll either way, it could slip back or it could go unstoppably forward.”

At the function where Will Alsop unveiled his proposals for Britomart, the speechmakers repeatedly made “planners” the butt of their jokes. Ludo Campbell-Reid sat there listening to the laughter, a smile fixed to his face. He gets that a lot.

“Things take time. I’ve been here three years. Let’s see where we are after 10.”

Alex Swney: “No one takes up [a senior role at the council] without the will. But, you know, they begin by thinking they’re going to change Auckland for the better, and they look up one day and they think, ‘I can’t take this.’ There is this overwhelming despair. People don’t know how to yell in this city.”

A Sorry Façade

Allan Matson doesn’t yell, although he must be tempted. There’s a kind of seething anger to this heritage campaigner, and it’s to his credit he manages to keep a lid on it. Failure to protect heritage buildings is one of the sorriest records of the Auckland City Council. “This was a lovely Victorian and Edwardian city in the 1970s,” he says. “And now it’s nearly all gone.”

Since 2003, the Resource Management Act (RMA) has required local authorities not just to sustain the heritage values of buildings on their patch, but specifically to “recognise and provide for historic heritage as a matter of national importance”. Matson, who works from an office in High St so tiny it seems smaller than some actual shoeboxes, says that law change has made no apparent difference to the conduct of the council. He spends a great deal of his time making submissions, trying to prevent demolitions, trying and trying to push the council to do its job according to the law.

Take that Canvas City building in Hobson St. It’s the kind of ugly duckling, neglected for years, that would scrub up beautifully if only someone cared.

Developer Dae Ju has been trying to get a consent to demolish since 2005, and Matson has been trying for even longer to save it. The council has proposed it for category-B heritage status, which means demolition could be approved. Right now, both Dae Ju and Matson are hoping this will change. Dae Ju wants no heritage classification, which would allow demolition or else force the council to buy the building; Matson wants category A, which would effectively preserve the building. For obvious reasons, Matson wants the reclassification done before the demolition hearing.

But council officers have advised the mayor the demolition hearing should go first, on the grounds that there is no point revisiting the classification if the building might be demolished anyway. Last month John Banks accepted this peculiar advice, although his office also told us he had “personally met with Dae Ju to see if they would agree not to demolish the building”. The council does not favour buying the building, “because of budget limitations but also in terms of setting a precedent”. (Since then, a date for the classification hearing has been set in early April — earlier than the date for the demolition consent hearing — which means the likely classification will be known when the demolition application is considered.)

Observing all this, Auckland Regional Council chairman Mike Lee describes the ACC approach to heritage as “Orwellian”. “They have a small army of professional heritage people who don’t appear to always have the best interests of heritage at heart.”

Matson has many examples of what he says is a lack of due process in the way the council goes about the heritage process. It’s common, he says, for them not to apply the provisions of the RMA that require all projects to have a heritage assessment, if heritage is a relevant matter. “If they [applicants] haven’t got it, that should be end of story. Council should be sending them away to get one. But they don’t do that. They say, ‘Oh well, we’ll process your application anyway.’”

Some of the private-sector consultants employed by developers to prepare their submissions are former council officers. Dae Ju, for example, is advised by Duthie’s former planning boss at the council, John Childs. Matson believes the relationship between current and former officers makes it harder for the council to be seen to be acting impartially in its role as a champion of heritage values.

Alex Swney struggles to understand why developers don’t always grasp the financial value of heritage buildings. He says there are four upmarket international retailers who want to move into Queen St but won’t come unless they can secure good heritage premises.

“There aren’t enough Auckland ratepayers to pay for what the city needs to become,” says Swney. “Government has to accept it has a role!”

Tourists on 73 cruise ships will disembark at the bottom of Queen St this season, looking for places to eat, drink, shop and be so seduced by the city they will decide to return. Buildings like the peculiar St Laurence octagon on Princes Wharf and the Westfield Downtown block have no role to play in that. But heritage buildings do, especially the Ferry Building, Customhouse, the Britomart station frontage. And, potentially, the very beautiful Dilworth Building on the corner of Queen St and Customs St East.

Currently, it sits there with a category-A protection, which is good, but it has the kind of retail tenants you would expect to find in any tourist-trap corner of town. Once, it was going to be part of the gateway to the city, with a twin on the facing Queen St corner. Just imagine if the council and the buildings’ owners and tenants and some genuinely imaginative architects took that seriously.

Last month, Aaron Bhatnagar called for “cultural heritage fund applications”. A total of $50,000 has been set aside and owners of property of heritage interest can apply for the money to help with restoration (a further $50,000 has been allocated to other heritage work). In Wellington, the comparable figure is $350,000. In Christchurch, it’s $1 million.

Money, or the lack of it, is the root of most urban-planning evil — at least according to Swney. He’s very hot on it. “There aren’t enough Auckland ratepayers to pay for what the city needs to become,” he says. Practically yells. “Government has to accept it has a role!”

Beyond the Red Fence

“I have a vision,” says John Banks. “For the waterfront.” He wants a Sydney Opera House-type building down there, and he doesn’t seem too fussed about exactly where.

All power to Banks for this vision, although it would be disingenuous of him to claim it as particularly his own. Every politician, planner, administrator, architect and miscellaneous public enthusiast I have spoken to dreams of the waterfront becoming home to a big new attraction that will draw the crowds, enhance the celebration of the city and its sea, and provide a focus for events of all kinds.

But where should it go? At the Tank Farm, which is the expressed preference of both the Auckland City Council and Auckland Regional Council (but which, due to the recession, will not be developed any time soon)? Or on the “finger wharves”, which is that part of the waterfront directly out from the bottom of the CBD and the Britomart precinct, and is preferred by Heart of the City and others?

And what’s the deal with those finger wharves anyway? There are three at issue: Queens Wharf, which handles the ferries but is otherwise closed to the public, and Captain Cook and Marsden, which are fully closed to the public and used much of the time as a holding park for imported cars.

Councillor Bhatnagar says he expects they will become home to a new cruise-ship terminal. It’s a common view at the city council. Cruise ships have become important to the economic life of the city and the current facilities are not adequate.

If a new terminal does go on the finger wharves, more of the area will likely be opened to public access, with boardwalks and small park areas, restaurants, bars, shopping, possibly entertainment venues, along with some continuing working port activity. John Duthie already has drawings showing cruise ships at Queens Wharf and boardwalks over Queens and Captain Cook.

“If you took just one of the piers and did something really good,” says Alsop. “You wouldn’t have an argument about the rest.”

But, as he confirms, this does not represent the official view of council. That is contained in a document released jointly in 2005 by the ACC and the ARC, called Auckland Waterfront Vision 2040. It states that cruise ships will continue to berth at Princes Wharf (by the Hilton), that Queens Wharf will remain focused on cargo in the short to medium term, and that Captain Cook Wharf will do the same “for the foreseeable future”.

The wharves are owned by Ports of Auckland Ltd (POAL), which in turn is owned by the ARC through its company Auckland Regional Holdings. POAL released its own Port Development Plan last year. In this, it indicated “a willingness to release Queens Wharf for public access within two to three years, and Captain Cook Wharf within approximately 10 years”.

It sounds more concessionary than it is: POAL wants the public, through the city council, to buy Queens and Captain Cook. But what are the chances of that? Ratepayers will not be happy having to buy something they already own. POAL’s position is the yes you say when you really mean no.

So, fancy seeing the red fence down in time for the 2011 Rugby World Cup? Don’t hold your breath. As yet, there is no agreed plan, let alone any timetable, to change the use of the finger wharves. It’s a classic illustration of the strategic planning problems affecting Auckland urban design: too many bodies with competing interests.

Will Alsop has a pertinent comment: “If you took just one of the piers and did something really good, you wouldn’t have an argument about the rest.”

The view from Mike Lee’s windows at the ARC is better than at the city council — he can see the Waitemata and green suburban slopes, although you do have to keep looking up and out. The middle and foreground are filled with hundreds of cars grinding through the motorway lanes at the edge of Spaghetti Junction.

Lee has worked hard to improve public transport in Auckland, but he is also a fierce defender of the whole working port staying right where it is. He knows people “don’t like cars parked all over the wharves”, but he also knows people like their cars, and he thinks we can’t have it both ways.

He says there’s really nowhere else for port activity to go, and he worries that if developers have their way, the finger wharves will be given over to more “high-rise tacky apartments” and more dreadful retail centres like the strip at the east end of Quay St.

Auckland has a “magnificent waterfront from St Heliers to the harbour bridge”, he says. Fifteen kilometres. Why worry about the mere two that have restricted public access?

Lee’s concern is understandable. He was heavily involved in the extraordinarily successful campaign waged in the 1990s to keep the ports in public ownership, and he doesn’t want to see that achievement come to nought. But privatisation is not the issue here, so why is he really so keen on the status quo?

One possibility is that he’s quite happy to argue about the finger wharves, because it distracts us from the much bigger question of what happens to Bledisloe Wharf next door — home to the containers and, if POAL gets its way, due for extended reclamation.

Bet you didn’t know there’s a technical word for a container. It’s TEU, which stands for “twenty-foot equivalent unit”. The biggest container ships that currently berth at Bledisloe carry 4000 TEUs and are taller than the Hilton Hotel. The new ones are much bigger: up to 320 metres long and able to carry 7000 TEUs. To work the new boats, eight giant new cranes standing 94 metres tall have been ordered for Bledisloe. Right by the finger wharves. And you thought a stadium down there might be a bit of an eyesore.

This is why Waterfront Vision 2040 puts the focus for public development so firmly in the Wynyard Quarter and the Tank Farm. They want to keep the working port where it is, and shift the people to the west.

There are questions of national as well as regional interest in the size and function of Auckland’s port on the Waitemata. But those interests will not necessarily be threatened if parts of the working port are moved. They did it in Sydney, and opened Darling Harbour to the public. They did it in Vancouver, and London, Baltimore, Seattle, Portland, Melbourne, Wellington. This is not a radical idea: it’s the norm.

The Man with a Pony

Peter Salmon is excited. He’s like a man whose daughter is having a birthday, and she thinks she’s getting a goldfish, but really he’s bought her a pony.

True, this is a guess. Salmon is a QC and former High Court judge, so he’s been well trained to keep a straight face. But still, behind that steady gaze and under the beautifully tailored shirt he seems very pleased about something.

Salmon is chairman of the Royal Commission on Auckland Governance, whose report was to go to the Government as we went to press and then be released to the public within a couple of weeks. If it is a pony and not a goldfish, we’re going to have some far-reaching solutions proposed for Auckland’s woes: not just in governance but in economic wellbeing, urban design, social cohesion and many other areas.

Salmon is chairman of the Royal Commission on Auckland Governance, whose report was to go to the Government as we went to press and then be released to the public within a couple of weeks. If it is a pony and not a goldfish, we’re going to have some far-reaching solutions proposed for Auckland’s woes: not just in governance but in economic wellbeing, urban design, social cohesion and many other areas.

The commission has taken a remarkably large view. Its members recognised from the start that the purpose of political reform is to make it easier to pursue economic and social goals, and in turn that these goals make fundamental demands on urban design: you need to get the transport right, preserve the heritage, encourage developers to act responsibly and bring new life to the relationship of city and sea.

They looked around the world at outcomes. Who was getting these things right? (Answer: Vancouver, Melbourne, Brisbane.) Who was not? (Toronto.) What were the governance systems that delivered these things? “We were looking at function first,” says Salmon, sounding just like an architect, “and then the form that follows the function.”

Vancouver comes up a lot. Why Vancouver? “They have very good public transport. They made a decision way back when motorways were all the rage not to have any motorways running through the city. In retrospect, it seems to have been a good thing.”

The commission has not discovered an all-purpose solution. “The interesting thing about those cities is that they were all very different. There can be a whole variety of solutions, depending on the history of the city and how things have worked out.”

It wasn’t necessarily about the money, either. Although Australian states pour money into the cities, that’s not true everywhere. “The provinces in Canada don’t play a very big role in funding local government, possibly not even as big a role as the [central] Government here.”

Nothing lasts forever. “I’m quite sure that a number of the cheap apartment buildings that have shot up around Auckland over the last few years are not going to have a very long life.” Salmon believes many other “absolutely stupid things” have been done over the years. Another example: “Cutting off the Domain from the rest of Auckland with the roading system.” But, he adds, “mistakes can be rectified, over time”.

How? “Quite a large part of that is to have a holistic approach to the waterfront and the city and linkages between them. Of course, that’s been a goal for some years now, but it hasn’t had the holistic approach that’s really necessary.”

That sounds like there will be no more letting the ports decide for the city.

And there’s this: “Leadership is another thing that has been stressed to us as being absolutely crucial. Quality leadership.” He shrugs, and adds, “There’s not much we can do about that, of course.”

Really? “Well, other than suggesting structures which might be attractive to quality leaders.”

Now that’s a space to watch.

HOW TO CHANGE THE CBD ON THE CHEAP

Maybe it is time to think really big.

Move the whole working port to the east; dig up Spaghetti Junction; put that already planned rail tunnel through from Victoria Park to Mt Eden station, with stops under K’ Rd, Midtown and elsewhere. They built the underground in Stockholm when the population was 1.3 million. In London, they started the Tube when there were just 1.1 million people living there.

Maybe some of this really will happen. But in the meantime, some things could be done right now, for relatively little cost compared with those massive projects, and they would have a very big impact on the quality of life in the city. Here are a few:

1. Move all the used cars off the finger wharves. Do it by the end of the year and store them (as a short-term solution) on the vacant land around the old Parnell railway station. Open the wharves to the public. Build some seating and shade. We don’t need to wait for a whole new development before the public is allowed in there.

2. Make preservation the rule. Lower the bar, so that for all buildings in the CBD with any heritage significance, preservation becomes the norm.

3. Give Lorne St landlords incentives to get better tenants. There are some good cafes, bars and restaurants there — and in High St — but not enough. If the Aotea precinct is to become the city’s arts area these streets need to offer better eating and drinking.

4. Keep raising the charges on cars. There were 57 million public transport rides undertaken in Auckland last year. In 1956, there were 100 million. We could set the fees for parking, road use and public transport so the former subsidise the latter and there’s a steep incentive not to drive.

5. Reward companies that discourage driving. The aim is for employees to benefit from leaving their cars out of the city.

6. Create downtown pedestrian malls. High St and some blocks of Queen St are obvious starters, although Queen St might be allowed buses.

7. Turn vacant lots into vegetable gardens. Give incentives to the owners of empty CBD sites — especially Elliott St — to convert them into community-run allotments.

8. Turn Quay St into a “boulevard of dreams”.

Will Alsop suggests Quay St should be the best street in Auckland. Why not stud it with many more trees and encourage the property owners to commission architectural showcases of all types, including renovated heritage buildings, so that, as you move along it or approach the city from the sea, a marvellous panoply of urban life lures you in?