Mar 2, 2018 Travel

Simon Farrell-Green was always suspicious of camping. Then he went camping.

Or maybe it was associations with childhood swimming camps over the summer holidays, spent at the Cambridge Motor Camp, and getting up early in the morning to train at the Cambridge Pool in preparation for the Auckland Swimming Championships each year while my mates were at the beach. (Possibly, for this reason, I am now pathological about holidays: just ask my wife.)

Cambridge aside, we never went camping as a family. But then, we were lucky: in the 1960s, my grandparents bought a bach above a white-sand beach on the Coromandel. It’s basic — a fibro shack with a falling-down bathroom outside — but it’s kind of a second home.

As an adult, if the bach wasn’t available, I’d rent one. There was the year we went to Ngunguru and rented a big farmhouse up in the hills that was owned by very tall people — well, we assumed they were tall, since the bench tops were really high and so were the windows — and was but a five-minute drive from Sandy Bay, and we’d take the dog down earlyish in the morning before 9am — dog rules on beaches, another story — and go for a swim and then head back to the house for a coffee and lie on the really big couches and read books and go to the beach again in the afternoon.

There was the year we rented a little house above the Hokianga Harbour — up a long gravel road with a steep walking path down to the harbour, where we’d wander down and have a swim at the little beach at high tide. Hannah was pregnant; we’d just got married. There was a hammock and a lush green lawn and a view that took in no other houses and distant wooded hills on the other side of the water, and later that year, as we started to wonder what we’d do for our summer holiday, I was a little saddened to see that the radio host Kerre McIvor had bought it: I recognised the hammock in a photo shoot.

They were lovely weeks spent in other parts of the country. Lovely weeks spent in houses, with running water and crockery and a roof that kept out the rain. And shade. Houses have shade. Tents, by and large, don’t.

For the first few years of our relationship, every time we drove or walked past a campground, she’d sniff and sigh wistfully and remember holidays in the tent. Then she’d suggest we go camping and I’d say something non-committal and kind of avoid the whole thing and hope it didn’t come up again, which it invariably did. At other times, she’d buy gear — that set of enamel camping cups, say, which might come in handy one day.

Then, a couple of summers ago, we were staying in a bach in Hahei and Hannah took me on a carefully composed wander through the Hahei campground, showing me the Allpress coffee kiosk and the little container selling wood-fired pizzas. Part of me loved this and part of me thought if I’m going to camp, I want to really camp, somewhere with no power and no water. Somewhere that doesn’t have a shower block and a kitchen block with a Zip water heater and a general sense of Hi-De-Hi. Somewhere where you have to drive over a rutted farm track to get there and where your camp sits under an ancient pohutukawa tree and you have a little white-sand beach just down in front of you.

Eventually, in a weak moment in the middle of winter, with the promise of a sandy hot summer holiday in front of me but no prospect of finding somewhere to stay, I succumbed. Let’s just bloody go camping, I said. Hannah looked shocked, delighted and booked that very evening, and I, of course, felt guilty that this very simple capitulation could make her so very happy.

There were a variety of reasons. Many of them were financial. We have very small children — the old two-under-two 30-something instant family — and 1.3 incomes and by the time our second was on the way couldn’t afford to rent baches any more, unless we went with 22 other people, which I was never a particular fan of in the first place, because I get funny with lots of other people around, especially in the morning when everyone is debating what to do for the day and all I want to do is go for a swim and not have to discuss every tiny little decision and when and who will drive and whether the tide is low or high and who is going to make dinner, which always seems to involve barbecuing sausages.

Anyway, in short, I realised, after a while, that if I wanted to give my kids the kind of beach holidays I had as a kid, I’d have to learn to camp.

We haggled and arranged and managed to find three sites next to each other: lovely sites, close to the beach, in the sand dunes in fact, and on Google we could see that there were huge big trees above these sites, and we couldn’t understand how such lovely shady sites hadn’t been nabbed by one of those families that take the same site every year.

By Christmas, we had the gear assembled. It’s not cheap, but then I suppose we own it now so it’ll get cheaper every year, right? We borrowed the in-laws’ 1980s green-and-yellow tent, still in pristine condition, and their bright-yellow barbecue. They also gave us a folding table and a nice air bed for Christmas, which Hannah felt was overkill and I felt was entirely necessary. Then we bought a two-burner cooker, a folding camp “kitchen” and some pots from The Warehouse. I insisted on taking a feather duvet and a Hario hand grinder and a V60 Pour Over and a kilogram of single-origin coffee beans from Coffee Supreme. Hannah drew a line at the Hario kettle but allowed me to take actual glass wine tumblers, and I went out and bought some very nice enamel plates for her Christmas present, and though she liked them, I think she would have preferred to take things that didn’t match quite so well.

We did a trial run with the tent in the backyard. Hannah stepped inside and sniffed deeply, and I felt at once guilty that I’d held out for so long, and apprehensive: what the fuck do I know about putting up a tent?

We arrived on a glorious afternoon on December 27. Hannah was pregnant with Marti; Ira was 18 months old and howled most of the way. And we arrived to find there were no trees. Or more particularly, they’d long since been cut down. Our fabulous site was in full exposed sunshine through the middle of the day, just when we needed our son to nap. We put up the tent and I wondered, quite sincerely, what we’d done.

At first, I didn’t get it. The sites were small. Our tent filled most of ours, so we were lucky to have friends next door who had just a small tent, which meant we could lord it with a big central area in between. We cooked on our little two-burner stove out of principle, then wandered down to the kitchen to wash the dishes along with everyone else. If you don’t take some kind of freezer with you, you store your meat in the little storage room, a garage filled with standing freezers. You label your meat with a yellow sticker and a Sharpie — Farrell-Green site 41 checking out January 7 — and then you put it into a freezer, and end up sharing a drawer with the Johnsons from site 63 checking out January 23.

Each day, the heat built and built and the tent got hotter and hotter, no matter how you arranged things to catch the breeze, and a couple of days it was so hot Ira would go down for his nap in nothing but a nappy and thrash around until one of us would put him in the car in the air con and drive to Whitianga and back. Then sickness came to the camp: my friend Tim first, then his daughter Fyfe, then me — and I spent January 2 in bed.

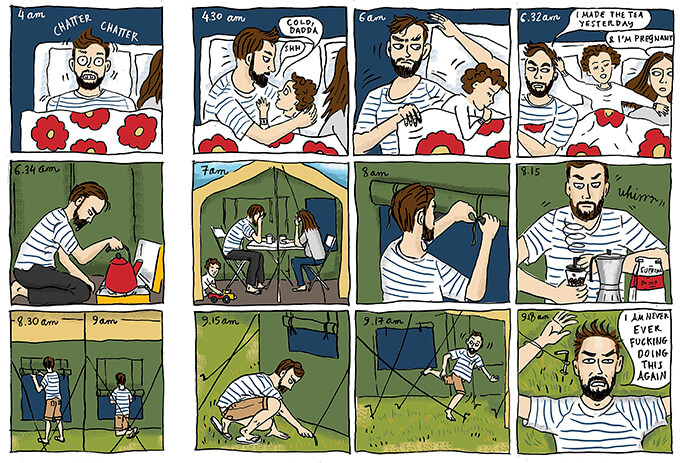

A day camping goes a little like this:

4am Wake up really cold, because you didn’t bring enough layers; it’s summer after all. But it’s not really summer, not high summer, and so you’re cold.

4.30am Get your son out of bed because he’s awake and cold, too, so you bring him into bed.

6am Find yourself on the far edge of the air bed, sliding slowly towards the ground.

6.32am Discuss who will make tea.

6.34am Put kettle on; go to use the toilet over there before everyone else wakes up.

7am Get up.

8am Arrange the tent flaps because the sun is up and it’s getting hot.

8.15am Make coffee.

8.30am Arrange the tent flaps.

9am Arrange the tent flaps.

9.15am Arrange the guy ropes.

9.17am Trip over the guy ropes while arranging the tent flaps.

9.18am Swear you are never, ever fucking doing this again.

And once that happened, time slowed down. I didn’t care what happened that day, or the next. My phone ran out of battery and I gave up trying to charge it. I read some books and mucked about on the beach with my son. There was the afternoon he spent hours in the creek making a dam until he was so cold his lips went blue and we had to carry him wrapped up in a couple of towels along the beach, only to find our canopy had blown over, so while Hannah warmed him up, my friend Thomas and I rearranged it.

We swam several times a day, in between naps, and rinsed off at the outdoor shower at the top of the stairs. Every couple of days, I’d have a proper shower in the ablution block, wandering back to our site over the dry grass in the early evening warmth, feeling scrubbed clean. We’d eat dinner early and go to bed not long after, going to sleep with the sound of the wind in the trees and the waves on the beach.

On New Year’s Eve, we left a party at a bach our friends were renting early and came back to camp, put the kids to bed, and I cooked spaghetti made from red onions and capsicums and an old tomato (which I’ve since tried and failed to emulate). It might have been shit, but it tasted fantastic and I’m pretty sure it’s because a cheap frying pan over a two-burner camp stove cooks with a particular type of intensity that cannot be replicated.

Ira loved it. If we bathed him and Fyfe at all, it was in a big flexi plastic bucket that we filled from a hose tap and topped up with water from the kettle, and he delighted — because it was that phase — in doing what we called Code Brown, which meant carrying the flexi bucket to the toilet block to empty it out. Ira took charge of the broom each day and swept out the tent while ordering us about. He spent the week on his plastic motorbike, meandering between our site and Fyfe’s, staring with undisguised awe at the big kids on their scooters and bikes.

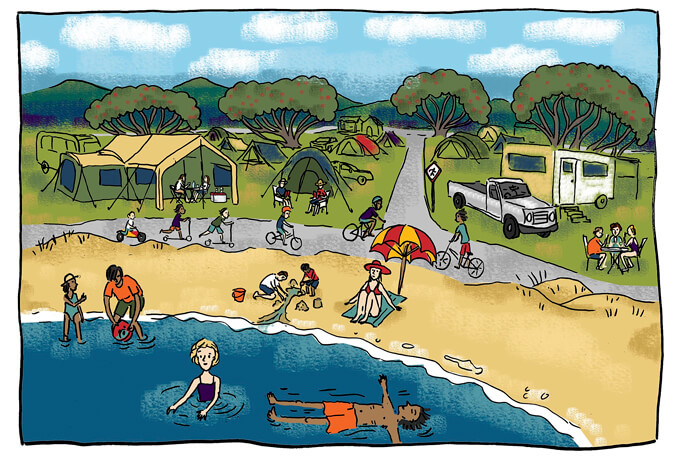

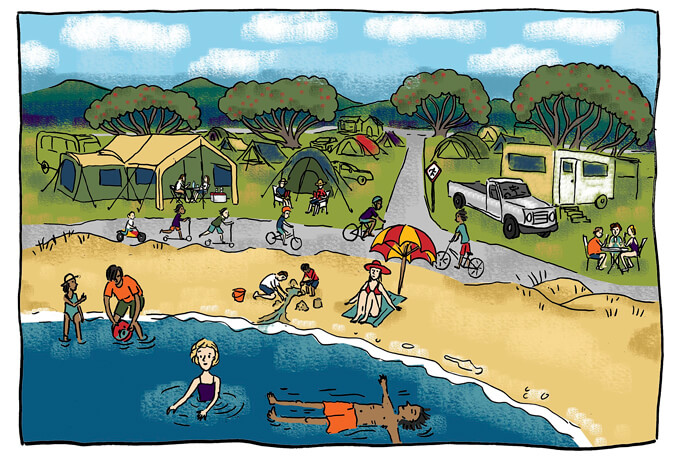

Each day, we went for a stroll and admired everyone else’s kit. There were people with very nice new tents with names like Gatorator and Expedition. There were quite a lot of trailers, and a lot of utes. One family — on, sniff, a powered site — had a fridge, a microwave and one of those little benchtop stoves. Another family sat in the front of their caravan each night and played cards, watching everyone meander past on the way to the utility shed. People sat out on loungers and camping chairs or just on the grass. Kids roamed the place on bikes, scooters and skateboards: Ira and his friend Fyfe tooled about on their plastic motorbikes. One evening, I poured myself a stiff gin and then Ira, Fyfe and I set about circumnavigating the campground. They occasionally flagged and asked to be carried a bit, but we eventually returned to camp triumphant, just as I slurped the last of my gin.

It wasn’t all bucolia: living in close proximity to others in tents has its moments. Drying the dishes one evening, I cringed as a woman gave a loud and detailed explanation to two polite Chinese tourists of how to cook corn in the microwave and then smugly left the room, at which point the tourists descended into howls of laughter.

Each morning, the bloke in the tent next to us got up to go fishing in his little aluminium tinnie, and we’d be woken by the clank of chains and the sound of diving gear being dropped in the bottom of the boat. “Fuck sake,” his wife said one morning. “Call this a holiday? All you do is fuck off and leave me on my own.” You could hear the confusion in his voice. The crayfish! “Fuck the fucking crayfish,” she said.

We came to the end of the week and the campground started to change. The “New Years” crowd moved on and the sites started changing. Campers would take down their tents, pack up their trailers and drive out slowly, and the camp staff would come by with a mower and mow the site flat, before new campers arrived.

Eventually, we packed up, too, and went back to the city, work — and our house, which suddenly felt huge. Around April, we got an email from the campground advising that as previous campers, we had first dibs. We booked the same site on the spot.