Apr 22, 2016 Fashion

Swedish denim brand Nudie Jeans is changing the way you look at jeans – even after they’ve worn out.

Above: Ruari Mahon, global head of public relations and communications at Nudie Jeans, was in New Zealand while Nudie Jeans had a pop-up station.

It’s a dilemma that almost every dedicated wearer of denim faces with each new pair: just as your jeans start to wear in, they start to wear out. It starts with a bit of wear around the knees, then one day you notice that they kind of hold your shape even when you’re not wearing them and this is the point at which they are at their most comfortable.

It’s one of the best things about denim – but it’s also the beginning of the end and it comes with the sad knowledge that your new favourite pair is on borrowed time. You know that eventually there will be holes and rips, and the fabric will get softer and thinner around the knees until it splits, and if you’re lucky you will get away without holes in unfortunate places, but if they do, your jeans days are sadly numbered.

When you buy Nudie jeans, though, and they start to wear, it’s really the beginning of the beginning. Since 2012, the company has been rolling out repair stations across its stores around the world, training up specialists in the art of repairing denim. Regardless of where you bought them, you can walk into a store anywhere in the world and have them repaired for free – or hand them in for a 20 percent discount on the next pair.

“ You break them in, you repair them, you either then reuse them or you give them to us to recycle…”

“It’s almost like a guarantee,” says Ruari Mahon, Nudie Jeans’ global head of public relations and communications, who was in New Zealand recently, wearing a skinny black pair of Nudies he’d owned for nearly six years. They’d been washed twice in that time, and had recently been repaired with blue and purple darning where they’d torn across the thigh. “You break them in, you repair them, you either then reuse them or you give them to us to recycle into new products. It’s kind of the life cycle of denim.”

Fashion is about selling new things, not fixing old ones, right, so is this counter-intuitive? “Yeah,” says Ruari. “And no. We’ve only seen sales increase – through wholesale, e-commerce and repair shops as we have increased the amount of stores and service.”

For Nudie Jeans, the programme has increased foot traffic in its stores and has only elevated the label’s cult status among its loyal fans. With the rise and rise of e-commerce, physical stores need to have more of a reason to exist than just selling clothes – they have to be a destination, with added value and an elevated level of customer service. “When you have that kind of ongoing trust at a deeper, emotive level… I think that’s a winning thing,” says Ruari, who was in Auckland recently to promote a pop-up repair station, which was staged in conjunction with Lincoln University, at the Auckland City Limits festival.

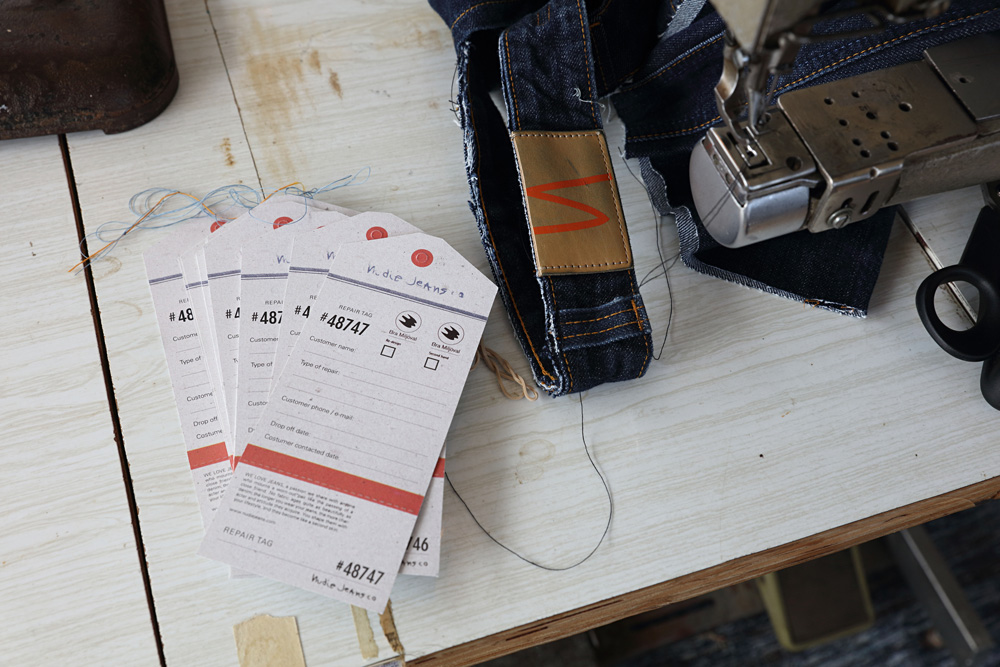

Loyal wearers of Nudie jeans could drop by and have their jeans repaired in a converted shipping container. There was loud music and a view of the stage and rather a lot of denim, as you’d expect – tote bags, a wall of jeans in various stages of gorgeous wear and two big sewing machines manned by young guys in Nike trainers and skinny jeans.

There was also a steady stream of people needing their jeans repaired, including one man who explained, slightly abashed, that his jeans always seemed to wear out in the crutch, and was that normal? (Oh yes, said Ruari gently, everyone’s jeans wear out in different ways.) And there was a woman who was wearing her Nudies to the gig, but who did want them fixed regardless: Ruari loaned her a pair to wear while her jeans were being fixed.

There’s no ‘right’ way to repair a pair of jeans, but there are general principles, and each repair specialist approaches it in a different way. At Auckland City Limits, a specialist sat at one sewing machine repairing a very faded light-blue pair of skinny jeans with a hole in the knee. He took a piece of equally faded, soft fabric salvaged from another pair, and sprayed it with glue, before attending to a few other smaller rips, constantly turning the jean around, then holding up to look. All in, they repaired more than 30 pairs of jeans that afternoon. (For now, Nudie loyalists here will have to continue taking their jeans to Australia for repair.)

Nudie jeans that are relinquished rather than repaired have been recycled into products, including rugs and tote bags. In one memorable project, 500 pairs were ground up and woven into new denim for Barneys of New York. (They’re still working out what to do with the zips and rivets, which are in storage at the Gothenburg HQ.) Another project called for their customers’ most beaten-up jeans, which were rehabbed – in one particularly memorable case, a New Zealand roadie’s jeans that had been five times around the United States on tour buses and stages and long-haul flights, wound up being worn by an editor at Vogue.

The brand’s unique DNA goes back to its early days and its founders who came from corporate brands. When they got together they wanted to create something that they truly believed in, says Ruari. “It wasn’t so much a reaction to something halfway through our business cycle to where we are now, it was very much from the start as we grew.”

Nudie Jeans has achieved its long-term goal of making 100 percent organic cotton a standard in all denim… there are no artificial fertilisers, pesticides or genetically modified cotton…

When the brand started in 2001, the first collections were a traditional dry jean, which isn’t intended to be washed. Since then, Nudie Jeans has achieved its long-term goal of making 100 percent organic cotton a standard in all denim. Now there are no artificial fertilisers, pesticides, or genetically modified cotton used in Nudie Jeans. As the brand has evolved and grown, it has sought to produce its products – wherever they’re made in the world – ethically. The first lines were produced in Europe, often in Italy, but the rate of the brand’s growth since 2012 has meant opening up production in the likes of India and Tunisia – where the same high standards of production apply. More recently, Nudie Jeans made supply chains completely transparent. You can log onto the website and see where your skinny selvedge jeans were made, right down to the subcontractors who do the dying or the laundering before dispatch. “That’s a fairly recent project,” says Ruari. And it’s remarkably honest. Issues are flagged and followed up: recently, one supplier had fallen behind on its fire safety policy, and this was highlighted in Nudie Jeans’ reporting for all its customers to see. Which might seem like small beer – safe to say you won’t find a sweatshop producing Nudie jeans, even if it is in India, but if you’re going to pay a premium for ethically produced jeans, this is very much the kind of information you want to know. And there’s honesty in admitting that they don’t have all the answers. “That’s the thing, our CEO Palle [Stenberg] will say, ‘We’re still to some degree putting one foot in front of the other.’”

But it is with recycling and repair that the company has really caught the public’s imagination. It started a few years back in Sweden, when Nudie Jeans began offering the discount for used jeans, which they then repaired and sold through the store. The initiative was recognised with a Swedish environmental choice award. Not long after, the first repair station appeared in the middle of the Gothenburg store, not far from Nudie Jeans HQ, and has since been rolled out through every store. “The actual sewing machines are not in the back room, they’re in the heart of the store and they’re operating all day long,” says Ruari. “It’s not treated as a separate kind of thing.”

For various reasons, most clothing sold in the West is now made in cheaper countries: traditionally India and China, but increasingly Bangladesh, Malaysia and Pakistan. At a time when consumers are increasingly conscious of the social and environmental cost of their purchases, it’s very difficult to know exactly what happens at every stage of the supply chain – and it’s even more difficult to control what happens with those products once they’re bought by the consumer.

Most supply chains, says Lincoln University’s head of Global Value Chains and Trade, Mark Wilson, are known as outcome-based; the traditional model for outsourcing. It transferred the risk to other companies in other countries at a time when brands wanted to reduce production costs – but it meant companies lost control, leading to well-publicised cases of worker exploitation and environmental destruction that seriously damaged several brands. “It creates a massive barrier for brand owners in the West to know what’s happening deep in their supply chain,” he says. “All the problems that brands have is because of issues that they have no idea are there – and no control over. A contract does not give you control over the supply chain.”

To control what’s happening, as Nudie Jeans does, brands are shifting to behaviour-based contracts, which set working conditions, environmental performance – the values by which a company might operate. “And the only way to solve that is to directly contract with different manufacturing firms,” says Mark. “It’s quite difficult – you really need to be hands-on.” That means staff on the ground, quality assurance surveys and audits. It’s taxing on management and staff, and it means constant vigilance and research. “Everybody operates with different cultural values,” he says. “You’re dealing with a whole lot of borders and customs. It may be acceptable in your host country, but it ain’t acceptable to your consumer.”

Closed-loop supply chains and recycling programmes are very difficult to achieve, says Mark. While they are an environmentally responsible thing to do, they are incredibly expensive. Reverse logistics cost between five and 10 times as much to get a product back from a customer as it does to get it out to them in the first place. “The smart people use the same channels to get them back from the customers,” says Mark – but even then, it’s difficult thanks to the cost of transportation and storage.

“At the end of the day we want our customer to buy the product because the jean fits really well and you look good and feel good in it”

Will consumers pay for value-added products based on socially responsible supply chains? “It seems to me that they do,” says Mark. Though it’s bloody hard work. “You’ve got to convince the consumer that it’s the truth – that’s when the trust develops.”

All of which means you’ve got to mean it. “We’re not jumping on a short-term trend,” says Ruari. “It’s just simply how we work our business. And at the end of the day we want our customer to buy the product because the jean fits really well and you look good and feel good in it. It’s organic – that’s a bonus. This is just how we should work.”

This article was first published in the Summer 2016 issue of Fashion Quarterly. Photos: Meek Zuiderwyk.