Aug 29, 2021 Arts

For an outsider, even a savvy one, the world of Art with a capital A is a glossy whirligig of champagne popping openings and indecipherable jargon, supercharged with the rush of pure capital. You can’t blame them. The foot that Art puts forward for the public (when it deigns to engage with the public at all) is one festooned in the kinds of value-speculation normally reserved for the esoterica of finance. So where does that leave the popular image of the romantically dishevelled artist? Does it still exist? Did it ever? If so, how does this notion of the artist reconcile with the art-market explosion, in which an untitled painting of a red cube or a black square can sell for more than a villa in Grey Lynn?

Perhaps the bridge between artists as inhabitants of society’s fringe (as they’re often inaccurately conceived) and artists as marketable producers and products, hasn’t got as much attention as the inordinate sums absorbed by this sector would suggest it deserves. And this bridge, of course, is the gallery. Or to be even more specific, the dealer.

Sarah Hopkinson has been in and around New Zealand’s art scene for nearly two decades. An Elam graduate, Hopkinson has spent time on both sides of the easel; she’s familiar with both cultural production at an artist level (having experience with smaller public galleries and artist run institutions), as well as being versed in the mechanics of more commercial dealerships and global art fairs.

You might remember her from Arch Hill’s Hopkinson Mossman (née Hopkinson Cundy and later, without Hopkinson, Mossman), a dealer gallery where Hopkinson and business partner Danae Mossman ran a programme that blended marketable and not-so-marketable artists to varying results. In hindsight, worlds away from her latest venture. Situated halfway down Anzac Ave, where Symonds stops being the university and starts being a series of sterile marina-hugging apartments, is Hopkinson’s latest gallery, Coastal Signs.

While being without a titular partner this time round, the new gallery is still a far cry from something she operates alone. If anything Coastal Signs approaches collaboration with its artists in a way that marries the edicts of prof- it-sharing with the benefits of a more commercial gallery, blurring the lines between what a gallery traditionally can and can’t do or be.

Assuming you’re not completely versed in gallery styles, the norms are the following: Public galleries, which can have culturally educative responsibilities and aspirations similar to museums and, similarly, are typically funded by a combination of trusts, donations, and central or local government; Dealer galleries, in which a dealer has a contract with the artists they show and take 40-50% of sales; and Artist-run spaces, commonly collective initiatives run by the artists themselves, which can to some extent replicate the dealer-structure in that they’re geared towards sales, with the advantage of omitting the dealer’s commission. If at some historic point these models existed in perfect parallel, that time has decidedly passed. Increasingly, there is a cross pollination of public and private models, the reasons for which being partly cultural and partly economic (the push-back of artist-run spaces for artists to have more autonomy for themselves, out from the contractual obligations of a dealer). Coastal Signs exists somewhere near this nexus. It is a commercial gallery with aspects of the collectivism found in artist-run spaces. Not only does every artist that contributes to the gallery in a given year get a share of profits, artists are also invited to the meetings in which it’s mutually decided what direction and objectives the gallery should prioritise in the coming year.

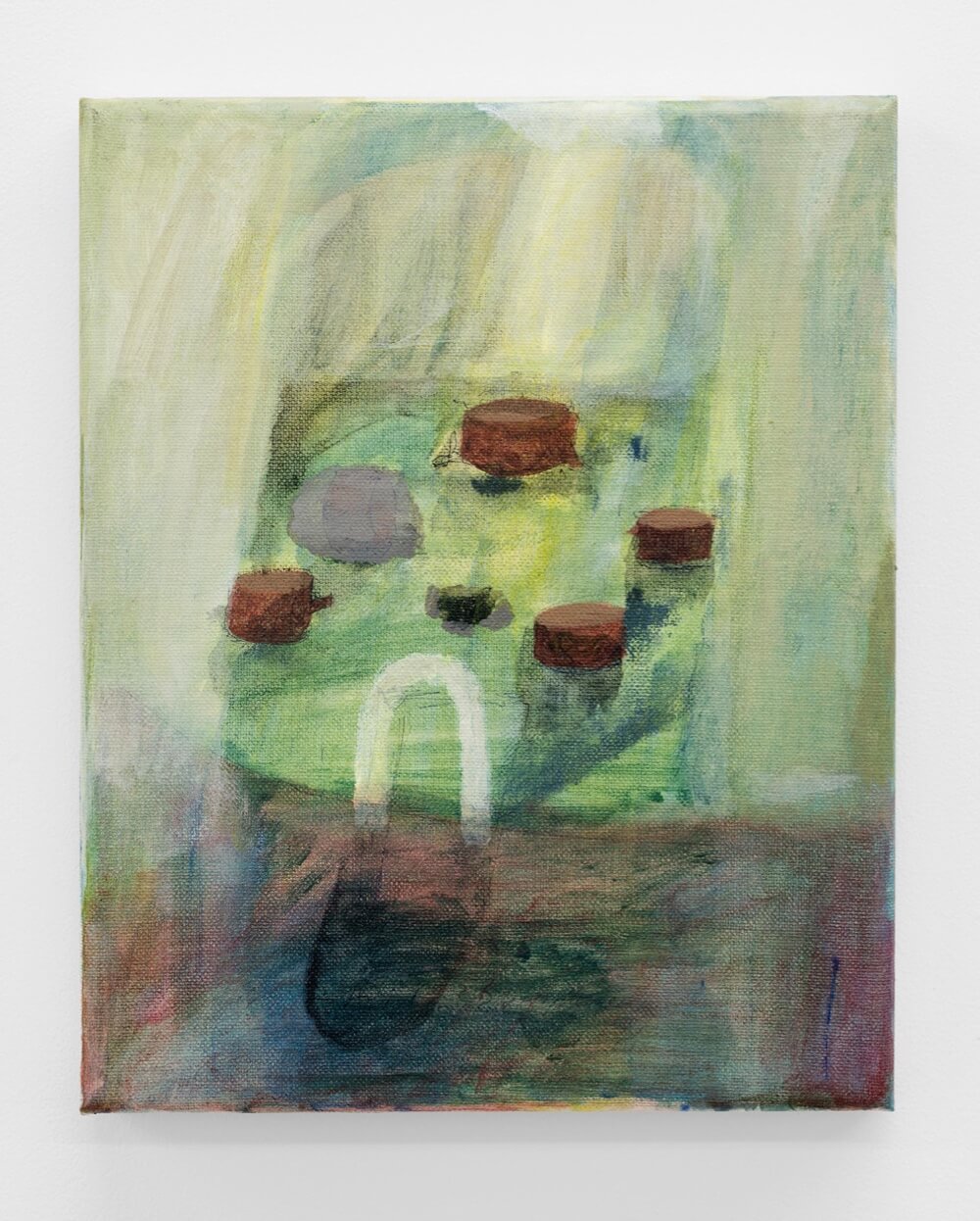

Ammon Ngakuru, Kindergarten, 2021 Acrylic on Canvas, 250 × 200 mm. Photograph by Alex North

The gallery’s first show, Ammon Ngakuru’s Pumice, could conceivably be establishing a precedent for the gallery, considering it’s thematic obsessions with vagary and, dare I say, death. If the first show in Coastal Signs speaks to the art world’s desperate need of structural overhaul (and an imminent demise via a defunct status quo), this feels deliberate. Ngakuru’s work has an aesthetically pleasant pastel-tone ethereality to it, something you might imagine backing the cover of a dream-pop LP, or the landscaping on LEGO packages (I mean this as a positive, honest). Combining more traditional canvas works with found objects, Ngakuru’s show is perhaps more aware of itself than established dealer galleries might otherwise permit in their plasma white shopping-aisles, generally being as risk averse as Wall Street financiers circa 2009.

“I like to think about the way that images and materials are assembled within an exhibition” says Ngakuru, “and how meaning and feeling can be produced depending on how connections between these are read. I’m also interested in thinking about the ways that history is presented and understood within a colonial context. I think these two ideas are related.”

Most of Ngakuru’s exhibiting experience has been with more collective spaces, though he’s not naive to the pitfalls of working alongside more dealer-oriented galleries. He acknowledges the contrast with working alongside Hopkinson and Coastal Signs. “So far we’ve been given a pretty comprehensive version of Sarah’s intention and idea of how the project might run and we — the artists involved and Sarah — have met to talk about this, he says. “As an artist who has less experience presenting work in a dealer context it’s interesting to learn from artists who have more experience working in that way, and what questions they ask that I might overlook.”

“Commercial galleries operate, typically, with a lot of opacity,” says Hopkinson. “It’s an old-fashioned but powerful idea, that the gallery offers a layer of protection from the big bad market. And, to an extent, it does; a good gallery acts as an interlocutor between the studio and the audience both in terms of communicating a conceptual project, but also just unburdening artists of a lot of admin and coms. It is tough for an artist to self-manage entirely – crucially because it would distract and take time away from their practice.”

Hopkinson recalls shock and surprise when inviting artists to write the gallery charter with her. “When we went to write the charter together some of the artists didn’t know what a charter was. I was like, ‘come on guys, I’ve represented some of you for fifteen years!’”

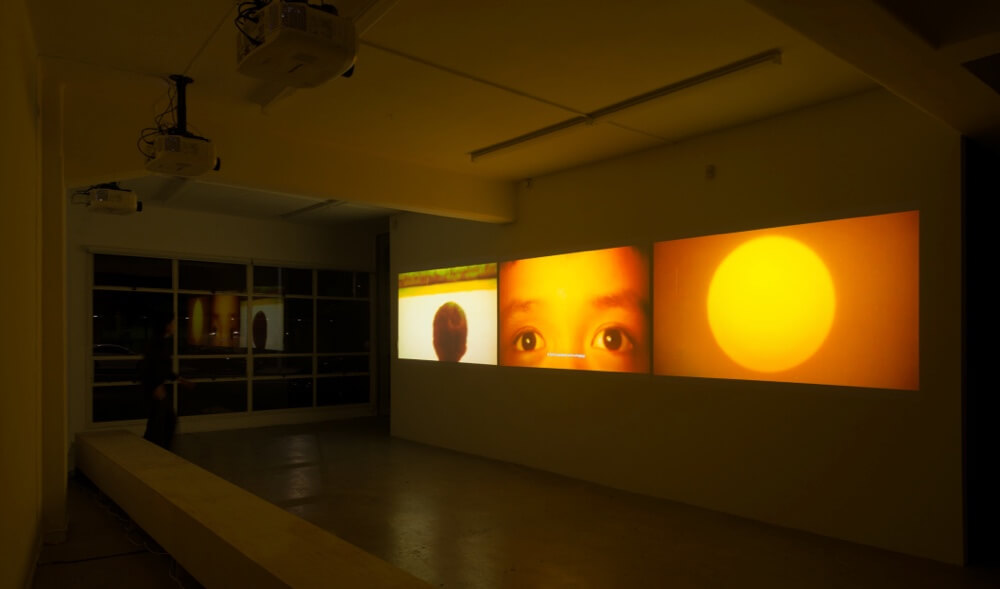

Qianye Lin and Qianhe ‘AL’ Lin, Thus the Blast Carried It, Into the World它便随着爆破,冲向了世界, 2021

In the artworld ecosystem, there’s the assumption that it’s players — artists, dealers, curators, writers, etc. — have some form of liberal education. Interestingly, the only link in this chain from production to sale to consumption that isn’t expected to traffic in knowledge attached to cultural production, are the collectors. But what is a collector? Or, who becomes a collector?

“It’s not necessary for a collector to have an art-school background,” says Jim Barr, who together with his wife Mary has been collecting art since the early-70s. “Collectors might become interested in art through school maybe, and then being a collector in relation to a dealer is very attractive because you’re treated like an insider.”

Referring to the opacity of the mechanics of a sale, Barr expresses a similar distance between himself and some of the details around dealer practice. “We have a pretty good grasp of how this world works, but I often wonder how the dealers make money when I look at what they do,” he says. “Mary and I tend to only collect a few pieces at a time, which often means we only have a few dealers we go through, sometimes just one. It’s more common for people to go through a wide range of dealers. And the people that we have dealt with, we’ve dealt with long term.”

In this respect, the relationship between dealer and collector could almost be seen as a collaborative exercise in ‘taste-making’. “The dealer provides the context in which the collectors buy the work, and different dealers will have different expertise, skill, taste, style and access,” says Barr. “Like Peter McLeavey for example, who was a ‘taste’ person. I mean people used to talk about ‘having a McLeavey’. They’d have a painting on the wall and say, ‘Oh that’s my McLeavey’, because it was McLeavey’s taste that was determining the sale. They thought his taste was the best so buying from him they’d be getting, ipso facto, the best”

One can’t help but make a connection between the ways in which dealers operate, and the frequently charisma-based wins of a successful real-estate agent. Like dealers, realtors are trafficking in significant assets, parading a property they’re hoping to pass on with overt marketing skills, cheerleading not just the quality of the house but in the same breath their reputations as competent sellers. And like dealers, the function of realtors is often seen with ambivalence as a custodial role in which market forces are overseen or ‘managed’ for a tidy sum, forces which I can’t help but feel, perhaps naively, could very well operate without the supervision of an intermediary.

Of course the character of these assets are vastly different but the stratification of these assets is so similar that they’re almost entwined, both being recently subject to ‘bubble’ effects which class them, over and above basic needs, as luxury consumables. “There is this old fashioned idea that art and money don’t mix” Hopkinson says, “which is absurd.” She mentions the 90s specifically as a time when big-monied patrons were introduced en masse, both privately and institutionally. It was during this era that artists like Damien Hurst and Jeff Koons (with a literal background in finance) began making art which engaged almost satirically with these market-driven impositions. It’s not that they necessarily invented the affluent-collector archetype, but certainly they were mainstreaming it to the point that, for the uninitiated, it stands as the pervading image for the art-world generally. Cultural production colonised by wealth. “The art world organises itself around a market,” she says, “and I think we should all (all of us, including artists) try to look directly at its influence” Hearing this from someone who is earnestly attempting to rejigger a potentially exploitative system from the inside, I’m reminded of Margaret Werry’s book The Tourist State (2011).

It’s a book about New Zealand’s interesting and fraught relationship with the tourism industry. Specifically, about how we have performed an indigenous character for overseas travellers, making New Zealand a carnivalesque ‘Maori Land’ in which an indigenous population is expected to enact a utopian version of itself, dismally absent of all the complexity and nuance (and wounding) of colonialism.

Here lies the danger of stratifying the value of cultural signifiers without engaging in context. A context which, in the dealer-gallery setting, it is the responsibility of a dealer to advocate for and communicate. Like Werry though, Hopkinson seems to understand her neo-liberalised sector not as one of defeat, but of potentially vibrant struggle. And perhaps like Werry, she will incite her counterparts to stand with more resistance in their shared and undoubtedly compromised field.

We can only hope.

—

This story was published in Metro 431 – Available here in print and pdf.