Sep 28, 2022 Metro Arts

Kia ora dear readers–

Spring is upon us and the latest issue of Metro is out in stores now. It holds the honour of being a dual editor special (one time only) with my and Lana’s tenures overlapping. (In honesty, Lana did the bulk of the work; I got to coast along in her slipstream.)

The spring issue’s arts section is teeming with great content including our much talked about list of 30 artists to watch (some of the city’s best and brightest); Anna Rankin’s profile of painter Anoushka Akel (an inspired pairing of journalist and subject); Vanessa Ellingham on Artspace’s incoming director, Ruth Buchanan, whose appointment has felt like a timely and judicious response to a call from many for a director with local connections to lead the organisation; Metro’s editor Henry Oliver on poet, playwright and novelist, Dominic Hoey; a studio visit with art and architecture’s favourite fabricator, Stephen Brookbanks.

As always, we have some short but considered reviews: Tom Augustine on Welby Ings’ debut feature film, Punch; Emil Scheffmann on the late and mythic Giovanni Intra and his book of writing, and Ammon Ngakuru at Coastal Signs. Tulia Thompson reviews Gina Cole’s new sci-fi novel, Na Viro (Pasifika Futurism, is how Cole describes it), and outgoing editor Lana Lopesi throws a mini-explosive — she thinks art is boring and a little too safe now — just before her departure.

Below are some exciting recommendations for what to catch in Tāmaki in the arts over the next few weeks. The city is coming back to life; the vibe has certainly shifted. But first, as promised, my belated appraisal of the Gilbert & George affair at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki — a show which no one really needed. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

— Tendai

Pictures Degeneration:

On Gilbert and George

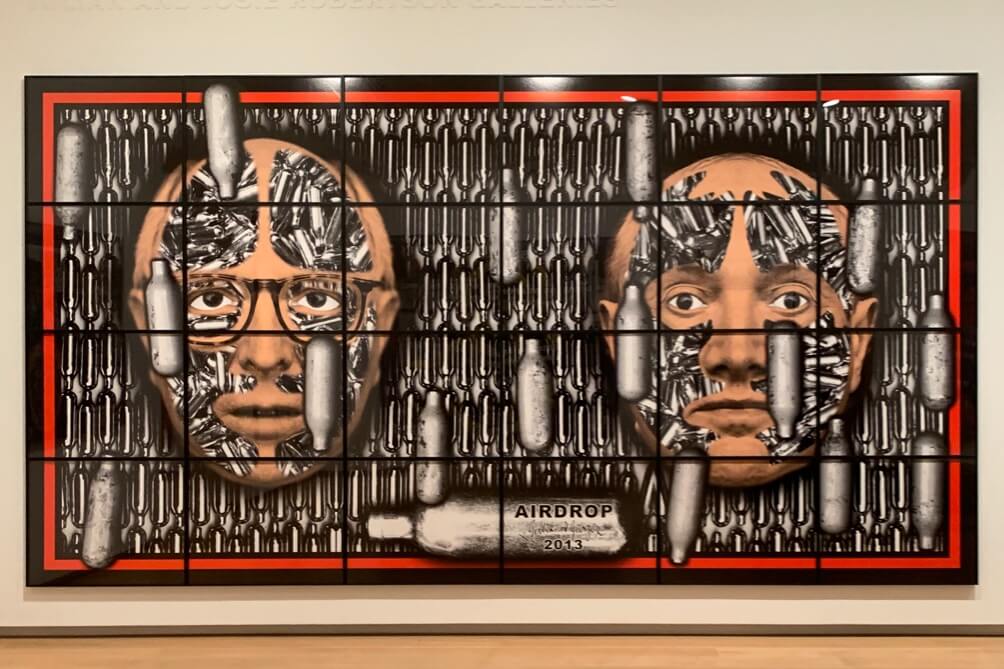

Nangs at Gilbert and George

If modern art is said to be at the expense of the masses, Gilbert & George have, in a reversal of its purportedly elitist impulses, made themselves the joke. It’s maybe imprudent of me, then, to take the class clowns at their word by writing this review, but I like a challenge. Afterall, I sense, beneath a veil of humour, something sinister being smuggled into the culture — and so many of the claims to defend it ring false.

Gilbert Proesch (b. 1943, Italy) and George Passmore (b. 1942, UK) met at Central St Martin’s School of Art in London in the late ‘60s. They bonded over their contempt for the overbearing insularity and formalism of their peers’ work, and that of the wider art world. Their response? To make their comportment and dress, and every mundane aspect of their life, into a ‘living sculpture’. Enter: the airless chamber of their universe — a cloistered world of dowdy tweed suits and obsessive, eccentric routine (they’ve dined at the same restaurant every evening for years on end, we’re constantly reminded). Gilbert & George (two people, one artist) sometimes speaks in an amusingly stilted back and forth, vollying between the former’s Austro-Italian brogue and the latter’s poshly accented received pronunciation. Meanwhile their rhetoric swivels from inanity to provocation, and back again.

What Gilbert & George presents is not so much a coherent set of ideas against what they claim to be the tyranny of modern art’s snooty intellectualism, but an attitude of turning away from the twentieth century avant garde, whose work, and ideas (read: theory) had by the ‘70s hardened into its own kind of orthodoxy. If we had to give Gilbert & George a slogan, “shock the bourgeoisie” would make a suitable rallying cry. But what happens when the once-scandalised middle classes become immune to art’s shock and vulgarity? After one employs the same shock tactics over and over and over, what is left — as in the recent exhibition Gilbert & George: The Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery — is a hollow shell of once-incendiary-art-turned-

If the task at hand in this exhibition were one of historicising, or simply memorialising, Gilbert & George’s earlier work, it might have been vaguely more interesting, though I doubt it. (The question often posed to me was, to put it politely, why would the gallery stage a show, at presumably such a great cost — Covid-era transnational shipping, large ads on buses, a glossy publication — on artists so irrelevant?) What we got instead was a laboured attempt to push for the ongoing “radicalism” of this pair. “Bold, provocative and pulsating with power” one brochure read. And then there were the usual boilerplate clauses about how they “challenge the status quo” and “champion alternative views”.

The work on display at Toi o Tāmaki was admittedly not the artists’ most provocative. No giant turds, images of the artists exposing their anuses, or racial slurs for titles. (The swastika appears a few times but in uncontroversial ways: as an object of condemnation, accompanied by the phrase “the only good fascist is a dead one”.) As the year’s pass, the pair’s work gets gaudier and more baroque to the detriment of its impact. (The Dusseldorf Kunsthalle exhibition in 1981, included in the publication is an example of their simpler and more visually striking work.) In these later works, we get a barrage of Union Jacks, the banal visual equation of nitrous oxide canisters (“whippets”) to explosives, and the facile aggregation of newspaper headlines whose origins (nowhere to be seen) might have told us something useful about the UK’s conservative media landscape as a site where power is contested. While the novelist Michael Bracewell’s writing in the accompanying publication lends erudition to a discussion of the series shown at Toi o Tāmaki, it only serves to prove that even with the best efforts, Gilbert & George’s best days as artists, like the bottoms they love to expose, are behind them.

To court a wider audience, their work has always taken on an accessible veneer, building in references and forms from mass culture and the everyday. These are things that the uninitiated, without specialist knowledge, can understand and respond to emotionally. Their use of the term ‘pictures’ denotes the work’s affinity with common images on billboards, television and in magazines. But the work so often hinges on basic equations: its glowing colours evoke stained glass so we’re led to think of how the profane is set against the sacred. Images are often layered and built on each other because, well, profusion of form amounts to a profusion of ideas and, better still, to a complexity of thought in which the world is not vulgarised into conflicting ideological camps.

In her introduction to the accompanying publication the Toi o Tāmaki director, Kirsten Lacy, reminds us that with their flag work (JACK FREAK PICTURES), Gilbert & George “isn’t taking a position about past injustice brought about by British colonisation” nor are they “anti-establishment, anti-monarchy protestors, […] striving for political overhaul or intervention”. But “they are cognisant of inequity in society” she tells us, “and driven to create a more just world”. It’s an attempt to have it both ways: to disavow politicised and historicised thinking and action, and yet somehow commit to creating a fairer world. The mental gymnastics required to reconcile these positions is dizzying but the art world is nothing if not agile, olympian even, in its capacity to make claims for justice while assuming a position of indifference to all that inhibits it.

Gilbert & George is free of creed and ideology, we are so often reminded. Theirs is a “humanism” undisturbed by petty partisan squabbles; they are concerned with things more universal and timeless: Humanity (“The essential tenets of being human apply to all people”); Freedom: (“we’re all completely privileged compared with the past … we can read any book, dance to any music”) (“We don’t have the vicars controlling us and we don’t have a dictator overseeing us, so we’re free”); Culture (“you can walk anywhere else in the world and stop a complete stranger and say Charles Dickens, something will come into that person’s head”). Then there are the attempts at aphorism, empty turns of phrase made to sound like something: “we want our Art to: bring out the Bigot from inside the Liberal and conversely to: bring out the Liberal from inside the Bigot”. Beyond the ahistorical presumption that ‘bigots’ and ‘liberals’ are distinct categories, I’m not sure what exactly they mean by that statement. But, as noted previously, theirs is not an art of ideas but one of poses. Too bad we’ve seen this one struck too many times to be amused by it.

Despite their many international museum shows, Gilbert & George consider themselves outsiders and therein lies their overidentifying with ‘the masses’ with whom they seem to want to have very little common. How did these two self-described supporters of Margaret Thatcher — an anti-worker demagogue, under whom the homophobic Section 28 was enacted — come to appoint themselves as spokespersons for ‘the people’? If Boris Johnson taught us nothing else, it is that bawdy clownishness is an ideal vehicle for the establishment to launder its reputation — lightening tragedy with hints of comedy — while smuggling into polite society a loathsome chauvinism that disguises itself as populist sympathy for ordinary people. The fact that Gilbert & George get to cynically deploy their eccentrities and their gay identity while doing this is a bonus.

And like all other opportunists, they will use identity strategically and selectively. In an interview with the Financial Times, the pair lament how at Tate Modern “it’s all black art, all women art, all this art and that art”. You’ll notice how, as the journalist points out, “art for all” fails to extend to “art by all”. For all its claims to universality, and its grand sweeping pronouncements, Gilbert & George’s rhetoric, like their art and their view of the world, is myopic, insular. Let the sun set on this little Empire of two and its romantic self-projection. The people could use a break.

Gilbert & George: The Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Exhibition

Auckland Art Gallery

Closed last weekend

Calendar

Po’ Boys and Oysters

Black Creatives Aotearoa

Basement Theatre

27 September – 8 October

Alice Snedden’s Bad News

Episode 3: Prisons

The Spinoff/YouTube

Live now

MENG

Directed by Steven Chow and Julie Zhu

MaoriTV On Demand

Live Now

Walls to Live Beside, Rooms to Own: The Chartwell Show

Auckland Art Gallery

Sat 3 Sep 2022 — Sun 26 Mar

Julian Hooper: New Paintings / John Ward Knox: Old Words

Ivan Anthony

10 September — 5 October

Shiraz Sadikeen: Ends

Coastal Signs

15 September — 22 October

Barbara Tuck: Down the River

Anna Miles Gallery

17 September — 6 October

Michael Parekowhai: A Parekōwhai Project

Michael Lett Gallery, 3 East St

23 September — 01 October

Areez Katki: Yes, I’m a garden

Tim Melville Gallery

27 September — 22 October

Jeanine Clarkin: Te Aho Tapu Hou: The New sacred thread

Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery

1 October – 20 November