Apr 23, 2023 Books

When Gina Cole was a small child, she lived in the lighthouse at Farewell Spit, where her dad was assistant lighthouse keeper. There were huge macrocarpa pines, bright lupins, and two cows that her father milked. But, apart from her two brothers, there were no other children. Her mum taught her to read and write. She pored over the boxes of books her father ordered through the mail. She had nightmares almost every night, thinking that the turning lighthouse beam, which would shine into her bedroom, was a monster.

Cole’s childhood reminds me of that of Margaret Atwood’s in remote northern Quebec — the Canadian writer grew up similarly steeped in nature, and without playmates, allowing her the solitude to explore immersive imaginary worlds. And Cole brings something of Atwood’s world-building to mind — her new science-fiction novel is a meditation on place and traverses deep space.

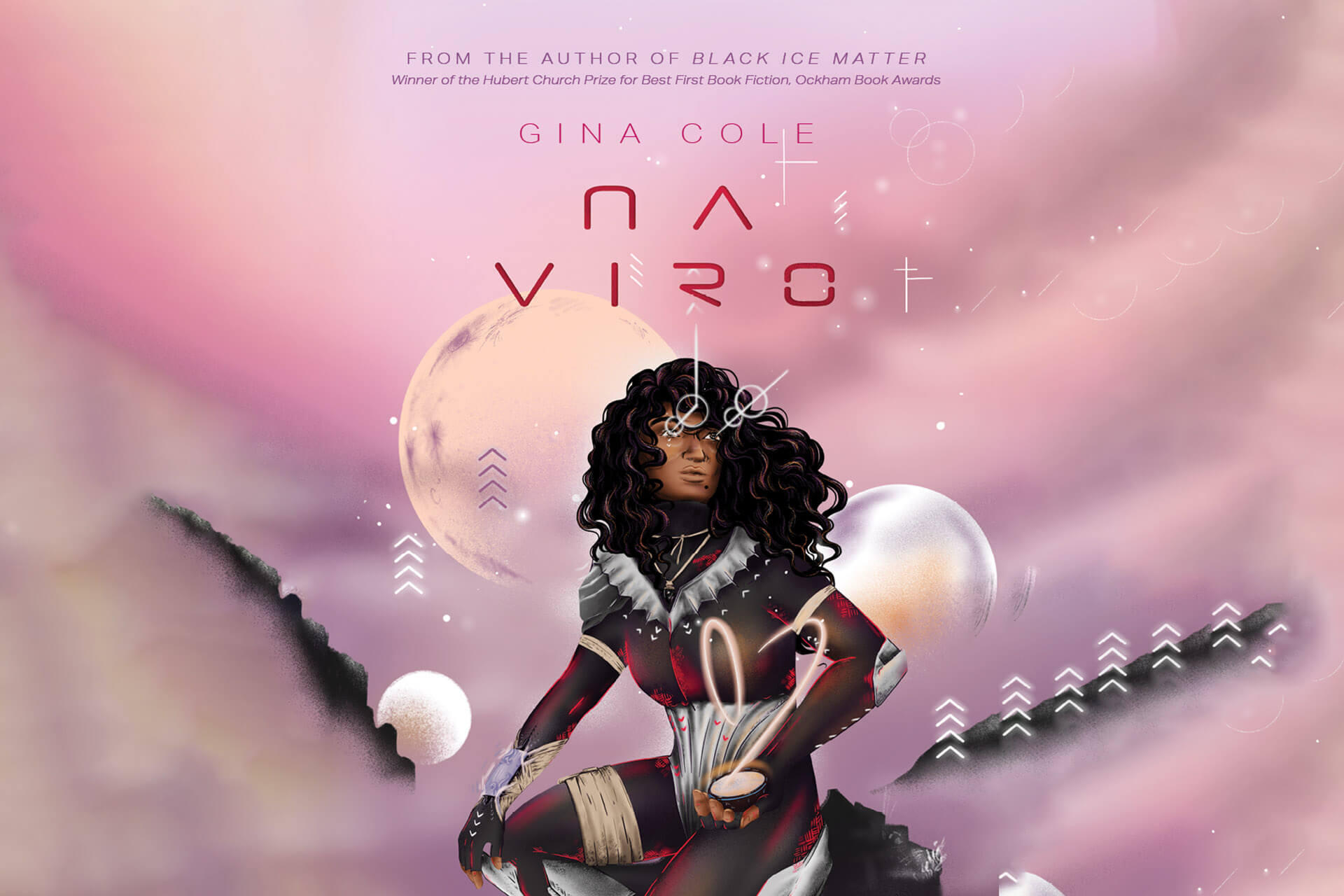

Cole’s first book, the critically acclaimed collection of short stories Black Ice Matter, was violent, immersive and smart. Na Viro is different. It is a sweeping space opera that spans tiny Pacific atolls and distant galaxies, expanding the Pacific into space. All characters are Indigenous. It’s a book unlike any I have ever read — a science fantasy about the Pacific region and the lives of Pacific women.

The novel follows Tia Grom-Eddy as she leaves her home island, Numa; joins the crew of an Academy flight captained by her distant mother Dani; and travels to Na Viro, the whirlpool, to rescue her sister Leilani whose data-gathering shuttle has disappeared inside it. Tia is abrasive and defiant, and has petty punch-ups with other cadets. The Academy is mysterious, an organisation which conducts training and space missions, like Starfleet in Star Trek.

Cole coined the term ‘Pasifika Futurism’ to describe Na Viro, drawing on the counter-futures she discovered while researching for her PhD about Pasifika science fiction. She was inspired by other regional forms of futurism by people who experienced racism and colonisation, including Afro-, First Nations and Latina. “Pasifika futurism recognises in artistic form a Pacific Ocean viewpoint of technology, and it provides a toolkit for recovering our history,” she says. “It’s rooted in our relationship with the Pacific Ocean, and with our navigational expertise travelling across the ocean, and our cultural, scientific practices of waka-building and wayfinding.”

There are lots of lush details in the novel that layer Pacific frames of meaning and wisdom into the futuristic narrative. Tia and Leilani are recognised by the Academy for their navigation and mapping skills. The whirlpool makes the skies act like the sea. There are puffer-fish spacecraft. The magic of Na Viro is that it maps onto the real Pacific. The fictional island Numa, Fijian for ‘mother’, is situated in the real Lau group, the Fijian islands closest to Tonga. Cole herself descends from Ono-i-Lau, one of the islands in the group.

As we talk, I notice a large map of the Pacific is framed on the wall of Cole’s lounge where we’re sitting. Cole is resting on a large red bean bag with her feet up (she has a bad cut from accidentally dropping a knife on her foot). “When you’re talking about counter-futures, you have to talk about colonialism and what the colonial project was trying to achieve — which was to erase us,” she says. “There is a lot of cultural trauma still in place impacting on us to this day, because of what colonisation did. So, one aspect is countering that narrative of us not existing. And writing a counter-narrative, which is we do exist, and we thrive, and we need to be there in the future.”

The kid who feared that the lighthouse beam was a monster has grown up to create her own monsters. The villain, Tia’s mother Dani, is so beholden to the Academy that she is prepared to exploit alien races and even kill her own daughters. Cole tells me she wanted to make sure the bad guys were also Indigenous. It’s an interesting stance, because I couldn’t help feeling that if Dani were Pākehā, her racism and exploitativeness would have read as within the social norms of the time — we would understand it even though it was abhorrent.

Earth needs a valuable resource called exo-ore which is plentiful on planet Thrae. Dani is involved in a resource grab, even though she is from a small Pacific island, and even though her ancestors were subject to the same treatment. Because she is Fijian and Tongan and is still exploiting alien peoples, I could only see her as a sociopath. I would have liked more about Dani, to understand her motivations, and why she ended up so evil. When Indigenous people are in positions of power, do we adopt the same behaviour as our former oppressors? Maybe some do. Or will. But colonisation and resource exploitation were tied to a long history of structural racism in the West — surely it’s not inevitable whenever resources are scarce? Certainly the reach of colonisation into space seems possible, and there are parallels home on Earth as climate erodes scarce resources.

Tia falls in love with sentient AI “embod” Turukawa, who helps the Academy and connects to the hive mind. Turukawa seems like a reference to seductive Cylon Humanoid “Number Six” from the series Battlestar Galactica, who can also retain memories in another body. Turukawa is lightly drawn, a sexy love interest without much complexity of her own: “A youthful embodiment, with short black hair framing her face, and a grey exo-suit of alloy fabric hugging her muscled body.” But it must be difficult to balance the demands of character across a pacy action plot, with so much world-building and a broad over-arching narrative. Cole’s writing in Na Viro makes me think of Christopher Nolan’s filmmaking, movies such Interstellar. There’s visual poetry, too, as when Cole writes, “Tia woke to find herself wedged between two angels.”

The Turukawa embod character draws on the origin story of the Fijian hawk goddess, Turukawa, who is mother to the first humans. In Cole’s retelling — and maybe this is due to the differing stories of different vanua — Turukawa is not a hawk but a red, black and orange chicken brought from Tonga. I found this translation difficult to read. I read it out loud to my partner in bed, even though he is Pākehā and so does not care at all. “Are you angry?” he said. “Or are you laughing?”

My response reminded me of my dad’s reaction the last time a Fijian narrative met pop culture. When the movie No. 2 came out in 2006, I had never felt so seen as through the depiction of the granddaughter character dutifully doing things for her grandmother, the matriarch Nanna Maria. For a start, I had never before seen a film about Fijian characters, let alone one set in Mt Roskill. My dad enjoyed it but couldn’t get past the detail that Nanna Maria, a marama of high status and mana, had drunk yaqona from an old plastic bucket instead of a beautifully carved tanoa. He was upset, on her behalf, that she hadn’t been sufficiently honoured. Even though she was a fictional character. Even though it was probably directly based on writer/ director Toa Fraser’s experiences of his own family.

In Fiji with Dad in the same year, I remembered being at a house on the first day of preparation for a funeral. Under a tree out the back, the other women and I shared grog from a plastic bucket while we made stacks of whitebread sandwiches for the arriving guests. The older men used the ceremonial tanoa out the front. It was a lesson in how we can have deeply held contradictory beliefs based on experience, worldview and gender. And yet when reading Na Viro, just like my dear old dad I was blinded by my attachment to my own worldview, inflexible even. I felt Turukawa our hawk goddess — an Indigenous Fijian goshawk — had a lot more mana than an imported fowl destined to be KFC.

The thing is, what I know — at least the saner or better-adjusted parts of me — is that as Pacific writers we can’t be too beholden to other people’s versions of cultural truth, even when, as with Turukawa, our own stories feel sacred. We have to trust our writers to create different iterations of our stories. Because when we trust our writers, some, like Cole, might create starpaths across galaxies.

Gina Cole, Na Viro

Huia Publishers

$35

–