May 14, 2014 Books

Me and my friends were listening to a lot of Björk at the time — and not listening to the nuns when they told us we should ask for an apple juice at a certain point in the evening, rather than another vodka. Mrs Breen taught honours English, and she was pretty loose with it. You were allowed to paint your nails in front of her, so long as you could discuss Milton while you did it.

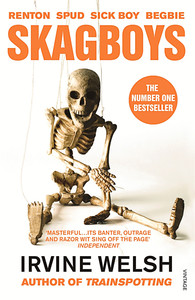

There was a group of us in her class who used to share novels. That’s how I got my hands on Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, along with Alex Garland’s The Beach, Bret Easton Ellis’ Less than Zero and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. For about six months in 1995, those four books were the only show in town. We passed them around like the one pot of Body Shop kiwifruit lip balm that always seemed to be making its way between us.

On the surface, there wasn’t a lot to link them. Dispatches from a nest of Edinburgh junkies, a Lord of the Flies scenario on a backpacker island in Thailand, anomie among the beautiful kids in various LA mansions and the misadventures of some precocious classics students in a New England liberal arts college. Four very different novels, written in wildly different voices.

Drug-taking, compulsive sex, living in a secret society, re-enacting pagan rituals – all sorts of thrills are on offer in these novels.

Looking back now, though, it’s easy to see what they had in common. They’re stories about growing up, or trying to, in a world that disappoints you. They’re also stories about what it’s like to be transgressive in one way or another. Drug-taking, compulsive sex, living in a secret society, re-enacting pagan rituals — all sorts of thrills are on offer in these novels. Thrills that I wanted to experience.

That I was shit out of luck is a matter of record. In 1995, I was that most ordinary of miseries: a reasonably imaginative teenager stuck in a boring city. I wasn’t going anywhere quickly, not even to the university down the road until my exams were finished. I had friends, but our interests were different.

I liked reading, and the X-Files. They liked putting on their sisters’ dresses and getting past the bouncers at the only house music club in the city. For lack of anything better to do, I went with them. That’s how I ended up in a sweaty back bar every Saturday, waving my arms half-heartedly to Carl Cox and avoiding the caresses of pilled-up ravers.

I was terrified someone would offer me Ecstasy, and I’d have to take it. They never did though, and looking back now, I don’t know whether that was lucky, or a pity. I thought I wanted the thrills, but in real life they scared me.

Which was where Mr Welsh, Ms Tartt et al proved so useful. Their stories were, in the main, narrated by characters I could relate to. Like me, they seemed to intuit there was something subtly wrong with the world in general.

Unlike me, they did whatever they felt like to ameliorate that discontentment. They drank heavily and took heroin. They had sex without consequence and engaged in criminal activity. One lot even killed someone, a murder immortalised in the famous first line of The Secret History: “The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

If I tend to quote this line frequently, it is because I am still stunned by the mastery of it, nearly two decades later. But the first line of Trainspotting is galvanising also: “The sweat wis lashing oafay Sick Boy; he wis trembling.”

Who starts a novel like that, in deepest Scottish idiom? No one I knew. This was my first taste of colloquial language in literature. The pure energy of a single voice, set down with brazen disregard for grammar and spelling. His name was Renton. He was a junkie, but clever with it. On the nod in front of a Jean-Claude Van Damme movie, but well able to pontificate on matters philosophical should you wish it.

No morals whatsoever, but he made that seem attractive. This was a trait shared by all the narrators of these novels. Renton, Clay in Less than Zero, the two Richards from The Beach and The Secret History, none of them has a moral compass. They pick up and discard their principles according to whatever each situation calls for.

What this means in practice is that their experiences tend to be a lot more interesting than the life of your average punter. Obviously, this is good news in the context of a novel. Character drives plot, mostly, and amoral characters make for memorable plots in most of these stories. Less Than Zero is the exception, because nothing much happens. Then again, that just underscores the theme of the book: the whole world is emptiness.

It goes without saying that this stuff transmits an itch to a reader. It’s impossible to spend time around people who refuse to conform to traditional notions of morality without having some of that urge to transgress rub off, even if those people are only imaginary creations. Those narrators were the first characters in literature who spoke to me in my own language. I wanted to sound like them, in fact I wanted to be them. I envied them their rites of passage.

I’m still thinking about them nearly 20 years later. Did any of them ever grow up, I wonder? Did they stop having bad dreams and get off the smack, and find nice girls to marry? I doubt it somehow. They were all lost boys, in one way or another. “Disappear Here” says the billboard that haunts Clay in Less than Zero.

Disappear Here. A useful directive when you’re a teenager with a need to be elsewhere. Escapism is the most childish motivation for reading, but at 17 there was still enough of a child in me to delight in falling down the rabbit hole.

Disappear Here. To an LA freeway where people are afraid to merge with one another. To a private college in Vermont where a group of classics students are restaging ancient pagan rituals.

Disappear Here. To a private island off the coast of Thailand. To the heroin-ravaged streets of Edinburgh.

Disappear Here. Between the violence and the addiction, and the amorality, all of these novels are strong medicine. But the 90s were a high point for mood-altering substances, whether you took them in pill form, or in sentences between two covers.

Noelle McCarthy will chair a session with Irvine Welsh during the Auckland Writers Festival, May 14-18. writersfestival.co.nz

Illustration: Anna Crichton.