May 7, 2019 Books

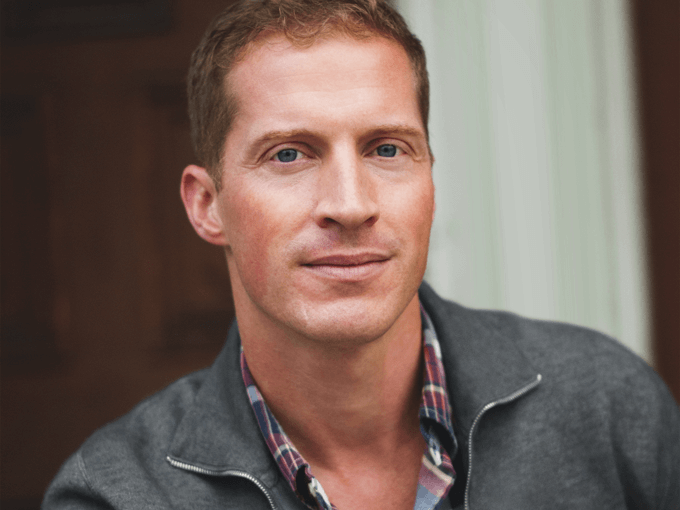

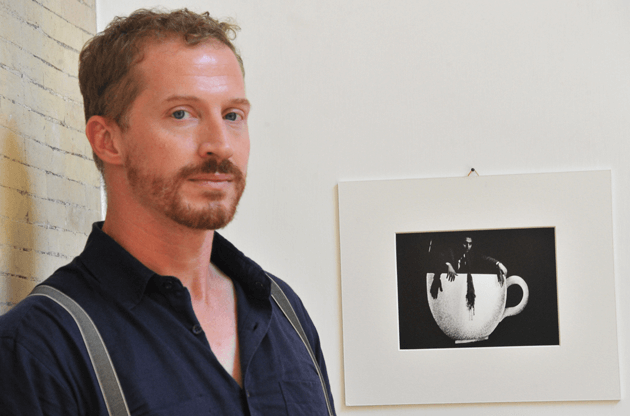

American author Andrew Sean Greer is the author of the touching and very funny novel Less. Following the around-the-world journey of aging gay author Arthur Less in his mission to avoid the wedding of his long-time lover to another man, the 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is deeply human and incredibly tender.

Tess Nichol (who rates Less as her favourite book of 2018) spoke to the charming and effusive Greer over the phone, catching him as he headed for afternoon cocktails in San Francisco on a Thursday afternoon. He spoke candidly about the total shock of winning a Pulitzer, American arrogance abroad, writing a happy ending for a gay love story, and the benefits of avoiding the lure of social media.

Greer will appear in conversation with journalist Noelle McCarthy and in a panel discussion at the Auckland Writers Festival later this month.

Metro: How does it feel to have written a book which won a Pulitzer, which deals with a character who also wins one [Robert Brownburn, Arthur Less’ former lover]? It’s funny as a reader to come across that, but of course you had no idea this would happen when you wrote Less.

Andrew Sean Greer: Of course not! In fact, the whole joke of the character winning a Pulitzer Prize in it is that it’s so impossible that even this well-esteemed poet in the novel, who’s in his 60s when he wins it, is flabbergasted. That is evidence of who I think is supposed to win a Pulitzer – that is, someone who is very much not like me.

How is he fundamentally different from you?

Well, he takes himself very seriously. I really loved writing Robert because he’s someone who speaks with gravitas and confidence and humour, and no bullshit. And I’m not sure I’m that kind of person. I can’t bear confrontation – but I think Robert relishes it.

In the book, I love the lightness of the wordplay and some of the little lines like “a cocked Spaniard” made me laugh out loud…

Ugh, that’s the worst line in the book! It’s so corny!

I know but I like it!

I can’t believe you picked that out, wow.

I think it’s because I have a real affinity with terrible puns, so the obviousness of it – I liked it that it’s corny, do you know what I mean?

My friend was telling me he doesn’t know why people think of puns as the lowest form of humour – they’re evidence of someone who, rather than a calculated joke, they’re doing something that’s just for fun, that there’s an intelligence behind it. There’s something sort of crossword-puzzley about it.

Definitely. And the wordplay, the muddling and mixing up of words which are nearly right but fundamentally wrong, that’s a big part of Less’ journey around the world, especially when he’s in Germany teaching a creative writing course to a class full of students who he can’t really speak to properly. What were you trying to achieve with that?

Certainly in Germany I was very specific in what I wanted. I knew he was travelling the world and I’m tired of watching movies or seeing in books where people in a foreign country have learned English fluently but get made fun of for having a funny accent. I’m like, ‘Oh my god they learned our language perfectly and we’re still making fun of them?’ Americans, and I don’t know about New Zealanders, don’t learn other languages at all. So I thought, what if I reversed it and gave Arthur the funny accent – that would reveal he’s really ridiculous in a circumstance like that. I wanted to turn it upside down, so someone who thinks of themselves as you know – Americans never think twice about having terrible accents in other languages because we have an arrogance where [we think] it’s nice to learn a few words at all, which kind of goes along with our national attitude. I don’t think Arthur’s that way, but a lot of English speakers are that way.

I was reading the book while I was travelling in Latin America and my Spanish was really bad, and I really related to that feeling of trying to express yourself, but you’re kind of like a baby.

Yeah, I learned Italian because I was living in Italy the last couple of years, that might have inspired it. God knows what I sound like. Italians were so generous to listen to me at all and they so rarely corrected me, but I think I sound like a four-year-old. Listening to an American speaking Italian is like hearing a dog sing – it’s not any good, but it’s amazing.

I finished reading Less feeling like a life that’s just ok or kind of accomplished but not super accomplished is fine, and our perception of our own failings are not often shared by others. So, where Arthur sees his inadequacies, people who love him see his vulnerability and sweetness. Do you think we often get it wrong – are we bad at judging how our own lives have turned out?

I’m certain that we are – and in both ways! There are those who think they’re geniuses and are dead wrong about it, or think their lives are examples of success and are not what I would call success. And then there’s the rest of us, who are [in our own opinion] forever a failure in some way, and it takes some re-adjusting of the lenses. To realise that you’ve got it awfully good and even by your own measures you’ve done awfully well and there’s plenty of time left.

In Morocco, the character Zora says to Arthur that no one can feel sorry for a sad middle-aged middle-class white guy, even if he’s gay. But I did feel sorry for him; I felt an affinity with that constant worry that somehow he wasn’t good enough; him being uncomfortable in his own skin.

I wanted to acknowledge his somewhat privileged state in the world, and yet say, you still can love him and feel for him, you know? I wanted someone to say to him, ‘Pull it together, come on. There’s actual suffering in the world and then there’s you getting on the wrong plane.’ And probably a lot of us often feel like ‘What right do I have to complain?’ Not even about our place in the world, but seeing our friends or watching the news. And of course you have a right to complain! But with humility.

A lot of that feeling of inadequacy or worry you’re talking about with seeing your friend’s achievements – that’s quite intense for Arthur having spent so much time with Robert who was so accomplished. I hope this doesn’t sound really obvious or reductive, but it feels like increasingly we’re encouraged to feel that way because of how publicly we live our lives online – even if you’re not comparing yourself to a Pulitzer prize winner.

I worry about that and Instagram is so tricky that way. You can get caught up in misunderstanding what’s actually going on. It’s like a depressive state where everything is bad news, the sunniest day can’t get you feeling any good because you feel it was sunnier in the past or somewhere else. I mean, that’s what depression feels like when I have it. I feel like getting too caught up in Instagram you can get a kind of Kardashian depression.

For sure – you see the successes of people but you don’t see the work it took to get there so you think ‘Oh why isn’t that happening in my life?’

Right, and the writers I see, all they do is post, you know, a picture of their new book or a draft they’ve finished and luckily I know what it takes for that to happen, but the poor beginning writers who see that must misunderstand.

Do you think it’s better to just opt out of social media altogether, if that’s possible?

Yeah. Yeah, I do. Speaking as a 48-year-old man. I’ve lived without it before, so at the moment basically I’ve come out of Facebook and I only reply to things on Instagram and Twitter, I don’t really post content. Because I don’t want to completely get entangled.

That is how it feels, isn’t it? Particularly on Twitter. That you’re entangled in an endless discourse.

And if you go away for a while you come back and you think, ‘What is everyone talking about?’ It’s a completely different world, a different mind set, everyone is set in some groupthink opinion you were not following so you’re just like ‘Why are we here? How did we get here?’ And it’s good to realise there’s other realities, not just this one.

In the book, Arthur’s told he’s a bad gay for never giving his characters happy endings. Does that make you a good gay for choosing the ending you did?

Ohhhhh, I don’t know. Of course that argument is absurd in every kind of way – that anyone would be a bad gay. In the United States we now have a candidate running for President who is an out gay man and he’s getting some flak from the gay community for not being gay enough. It cracks me up.

Because part of diversity in storytelling, and of not just tolerance but acceptance, is that people are allowed to just be who they are right, they don’t have to fit into a ‘good’ narrative?

And especially for LGBTQ people, they’re not growing up in a queer community – they’re coming out of everywhere. The more people are coming out the more we’re seeing people who are ordinary, you know, or who we don’t agree with any of their politics or real surprising figures who 20 years ago when I was out, these people were in the closet so I thought all gay people were bohemian, wildly left, progressive, marching on the streets. [But those were] only the ones we could see.

When there’s only a handful, or not enough gay stories, I do see people saying ‘I’m tired of seeing sad gay stories’ – it must feel good to write one with a happy ending.

Well, I did it on purpose. Not as a corrective to any queer literature out there, but I just felt like … you know what, I’ll make it even more personal. I have been trying for years to write a book with a gay protagonist and I couldn’t do it, because I kept veering towards a self-pitying melodrama because the character was too much like myself. I would kind of become a 19-year-old again, and it was no good. I couldn’t do it. And then somehow when I decided I was going to write a comedy and I knew I would give it a happy ending, I was liberated to write that story. So it was really in a way a writer’s choice and not a political choice or a gay man’s choice. I’d written sad endings plenty, I know how to do that. It was a challenge to see whether I could write a happy one.

So what’s next?

I’m writing a new novel. My immediate reaction after winning the Pulitzer was now I can focus on writing a new book, so I’ve been trying to do that. I move slowly. But right now you’ve caught me – I’ve just left the cafe where I was with friends with our headphones on working our books.

That’s got to be a writerly cliche right?

In San Francisco in a cafe? Yeah. And there’s usually a cocktail at the end of it!

I guess it is 2pm where you are.

I don’t need judgement right now!

Not judgement, only envy.

I’ll wait till 4.30.

Andrew Sean Greer will appear on the panel the Unwritten Rule with fellow authors John Boyne, Carla Guelfenbein and Anne Kennedy on May 17, and in conversation with Noelle McCarthy in Less is More on May 19 as part of the Auckland Writers Festival. Tickets $20-$25.