Apr 26, 2016 Books

Counting down the days to the Auckland Writers Festival? Here’s part two of our book columnists’ guide.

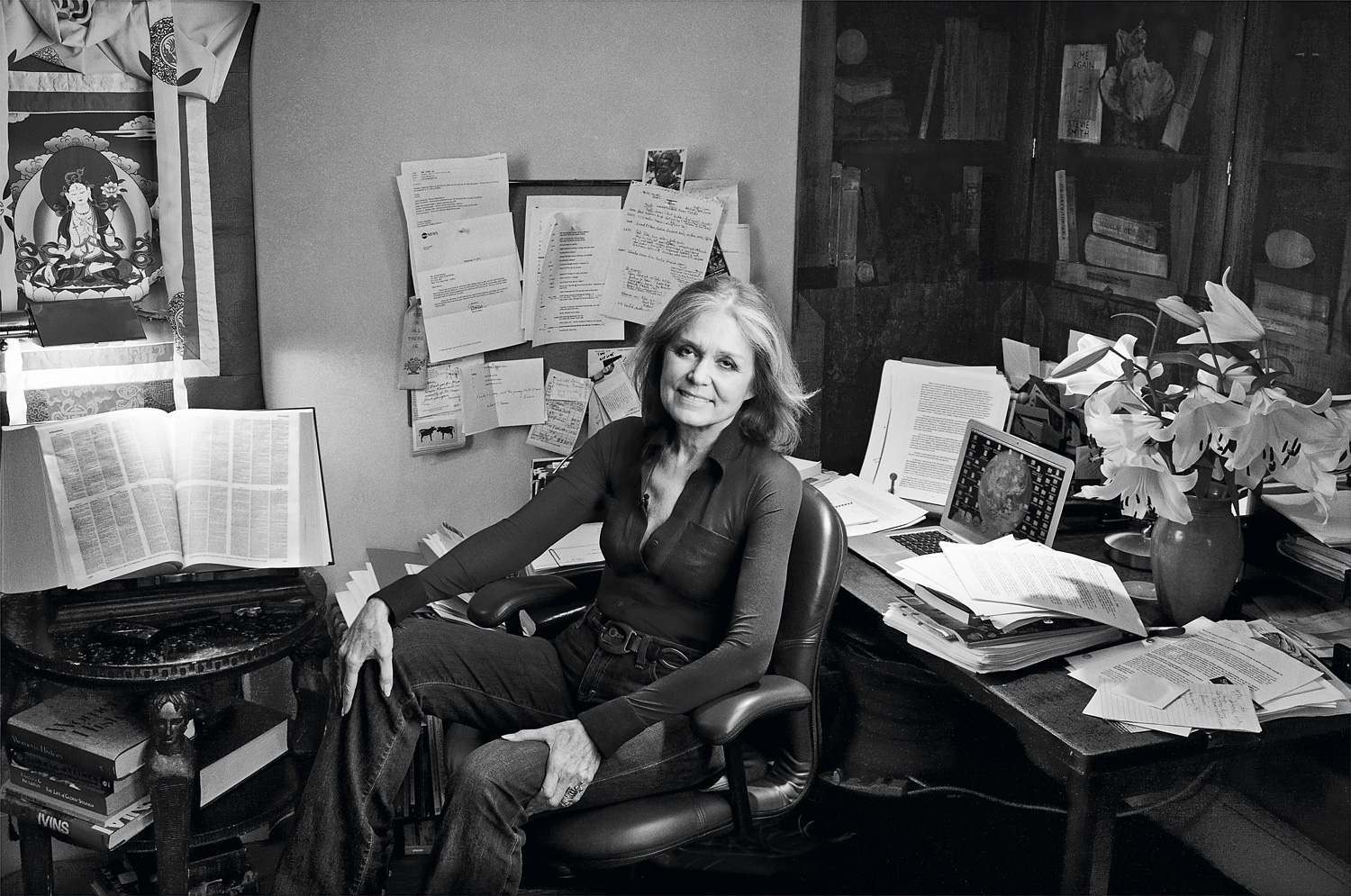

Gloria Steinem

When she graduated from Smith College as an outstanding Phi Beta Kappa student, Gloria Steinem’s father, Leo, worried about her fate. Once self-employed as a dance pavilion manager, Leo sent her a job advertisement for a dancer in a Las Vegas chorus line to be named the “Hi Phi Betas”. “Kid,” he wrote, “this is perfect for you!”

Steinem’s 2015 book My Life on the Road — an insightful memoir of different kinds of travel — begins with affectionate memories of a loving and kind father.

Only later in life did she realise that, just as her father loved the insecurity of making a buck on the road as a small antiques dealer, so she had also chosen a life of insecurity as a journalist and political organiser. While her father chased a dream of great wealth around the corner, Steinem’s dream has been of thoroughgoing political change.

The change she is most identified with, of course, is feminism and the founding of Ms. magazine in 1972 — the same year Broadsheet was founded in Auckland.

Feminism was a Western global phenomenon and Steinem was at the heart of it in New York. My Life on the Road details the ways in which travel has brought her new insights. The experience of listening and sharing in women-only railway cars in India during the late 1950s led to a lifelong habit of learning — about politics and prejudice from taxi drivers; about the indignities suffered by female flight attendants, “ornamental young women” hired by airlines with slogans such as “She’ll Serve You — All the Way”; about the lives of truckers and the way pimps work truckstops and the better safety records of husband-and-wife driver teams than those of men driving alone. Her craft at writing allows readers to enter the taxi, the plane and truck stop with her and leave having found a new perspective on workplaces and individual lives.

Steinem’s craft at writing allows readers to enter the taxi, the plane and truck stop with her and leave having found a new perspective on workplaces and individual lives.

Steinem is a convert to “talking circles”, which she first experienced in Indian villages while working with Gandhian non-violence groups in the 1950s. Listening to others in a respectful, non-hierarchical environment has become a political commitment.

That kind of sharing spread like wildfire in the 1970s feminist movement and lifted the lid on all kinds of previously private oppressions. For Steinem, the 1977 National Women’s conference in Houston, where she was asked to act as a scribe, was a turning point. The conference brought together women such as those in the American Indian and Alaskan Native Caucus who had never had the opportunity to meet before. Through those meetings, and looking for language to convert concerns into resolutions, Steinem learned about racism and poverty, family separation through deportations, and Native American treaties that had been ignored, leading to language loss and dispossession. After that experience, she saw that American Indians had much to teach about gender equality and democracy.

Steinem has great openness to change and to learning from others. At first terrified of public speaking, she gained confidence by doing it alongside a friend.

Travelling in the South with activist and lawyer Florynce Kennedy, the pair were occasionally accused by men in the audience of being lesbians. Steinem learned to answer with a disarming “thank you”. – Barbara Brookes

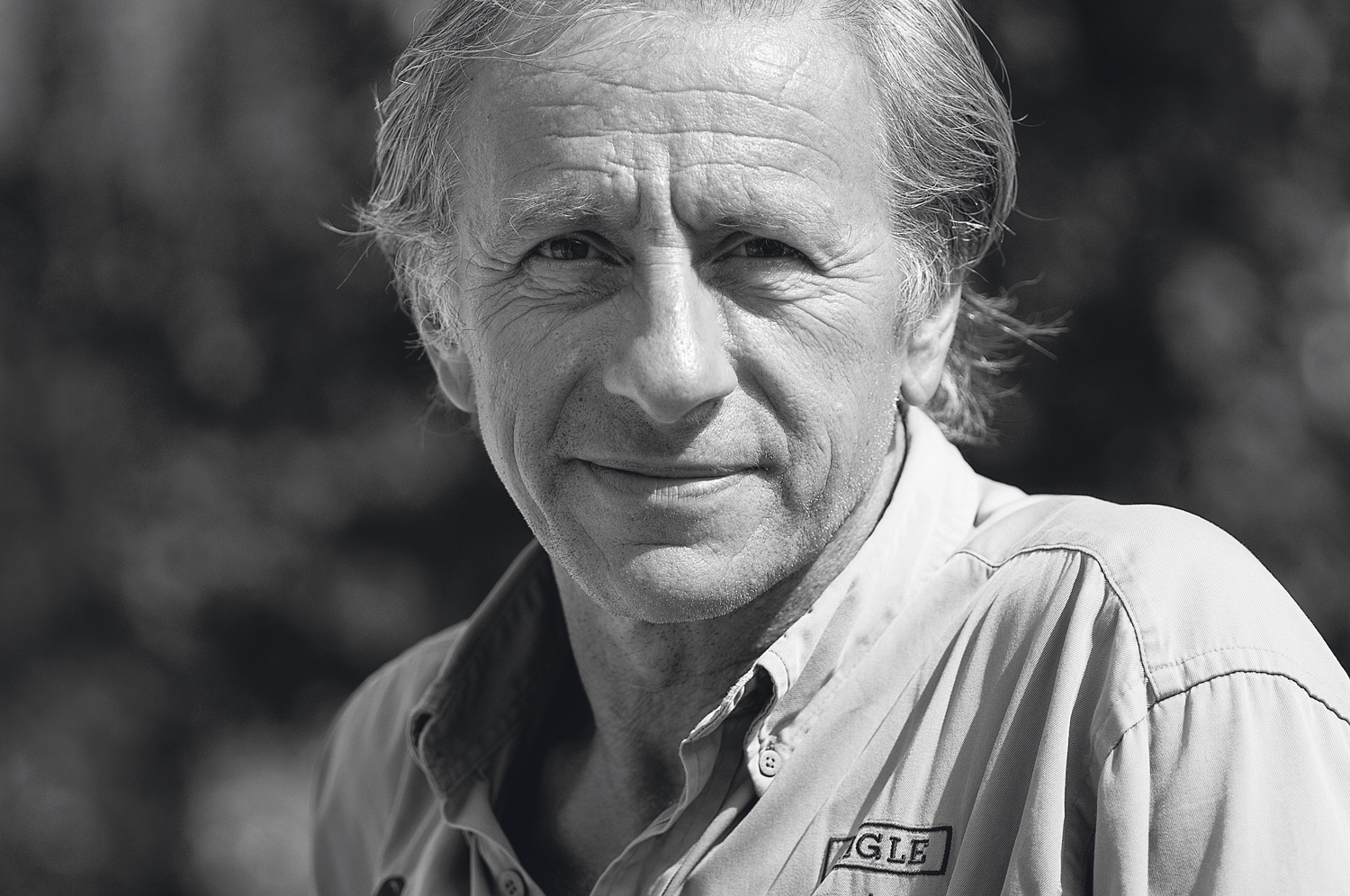

Paul Muldoon

On the wall there was a poster, black-and-white, of Contemporary British Poets. Blake Morrison, Andrew Motion, Craig Raine. Heaney, Hughes. They were mostly men, at a time when I didn’t notice things like that: this was the English Literature graduate room, Massey University, in the mid-1980s. Serious-looking men, brooding, except for one, whose face looked softer, quizzical, amused, owlish. Paul Muldoon. The story — probably apocryphal — goes that his teacher sent a few of the 17-year-old schoolboy’s poems to Seamus Heaney, asking what he might do to improve them. Heaney’s reply: “Nothing.”

His teacher sent a few of the 17-year-old schoolboy’s poems to Seamus Heaney, asking what he might do to improve them. Heaney’s reply: “Nothing.”

Heaney eased the passage for Muldoon’s first book to be published at Faber & Faber, still the most prestigious poetry publisher in Britain. Muldoon somehow emerged fully formed, mature, distinctive, idiosyncratic, with a touch of polymath genius. Like Heaney, he resisted assuming the role of public bard, a spokesman for Ireland in the years of conflict that reached their nadir in the Bogside Massacre, otherwise known as Bloody Sunday, in which 13 unarmed civilians were shot dead and another 13 wounded by British paratroopers. Like Heaney, Muldoon didn’t ignore the Troubles, but wrote about them obliquely.

Heaney addressed sectarian violence through poems about ancient bodies exhumed from bogs; Muldoon addressed Bloody Sunday through poems about the oppression of Native Americans.

Heaney was a mentor and an influence, but Muldoon has always gone his own way. His poems are like no one else’s, and he is closer, in his love of wordplay, wit, far-fetched rhyme, farther-fetched comparisons, and rejoicing in arcane bits of knowledge, to the Metaphysical poets of the 17th century (in particular, John Donne), than he is to those of the 21st. “The most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together,” Dr Johnson complained of these poets, and the same charge might be levelled at Muldoon.

But playfulness doesn’t mean lack of seriousness. It’s characteristic that a sonnet sequence of his describing historic battles all beginning with the letter “B” should omit, and thus focus attention on, the glaring contemporary example — the Battle of Baghdad.

Muldoon’s poetry is rooted in his native County Armagh and in the,l small village of The Moy near where he grew up (his collection, Moy Sand and Gravel, won a Pulitzer Prize), but from this intensely local source he accesses what is universal, as his Irish literary forebears — Yeats, Joyce, Kavanagh, Heaney — also did, in their different ways.

Nowadays, Muldoon is very much the public man of letters — poetry editor at The New Yorker, professor of poetry at Princeton and Oxford, sometime musical collaborator with the late Warren Zevon. For all that, he still goes his own road. The essays he wrote during his Oxford stint are noted for their eccentricity as much as their ingenuity. His poems continue to provoke and mystify. He’s still the poet my 23-year-old self yearned to be.- Tim Upperton

Suad Amiry

Suad Amiry became a writer through a predicament of place, time and a mother-in-law. The place: Ramallah on the occupied West Bank. The time: November 2001 to September 2002. The predicament: a city-wide Israeli army lockdown. It was 42 days of military curfews, and an occupation inside too — by her 91-year-old mother-in-law, rescued from her home near Yasser Arafat’s blockaded compound. Amiry’s writing began as emails — “a form of therapy” — to friends and relatives about her constricted life.

“I became a writer by pure accident. Sharon and My Mother-in-Law is a success because I didn’t have a reader in mind,” she tells me by phone from New York. “I was free just to say things and joke. It took a mother-in-law to be with you to write that book.”

Published in 2003 and translated into 19 languages, most recently Arabic, the book is a bitingly funny, tragic account of life under siege, the ongoing daily discriminations and absurdities. “I twisted my head half circle towards him and with owl-like eyes I started staring at him,” Amiry writes of an interaction with an Israeli soldier at a checkpoint. The tactic so unnerves the soldier he takes Amiry’s husband, Salim, to his superior and reports: “His wife was staring at me.”

Amiry continues to write about the Palestinian condition. Nothing to Lose But Your Life explores the hazards for Palestinians finding work and Golda Slept Here bears witness to the expulsion of Arabs from their homes in West Jerusalem. Amiry loves telling stories and warns me she will keep telling them unless I interrupt. She’s very verbal. Her chosen, more visual, field is architecture. Dyslexia makes writing taxing, but it doesn’t stop the storytelling. “As Sharon came about, I realised it was the story that people loved rather than the articulation or specification of the language.”

Born in Syria in 1951, Amiry grew up in Jordan. Her parents fled their home in Jaffa, Palestine, during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. She studied architecture in Beirut and was drawn back to Palestine in 1981, teaching at Birzeit University. The place had an immediate effect: Amiry shifted her research to vernacular architecture and conservation, founding, in 1991, Riwaq: the Centre for Architectural Conservation, dedicated to preserving Palestinian buildings. She also participated in the 1991–1993 Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations in Washington.

Golda Slept Here retains the sense of absurdity found in Sharon. “How can I be an absentee when I am standing right in front of Your Honour?”, an Arab homeowner asks an Israeli judge. Imbued with deeply personal stories of loss and suffering, Golda has a darker edge as it traverses the injustices of Israel’s absentee-landlord laws that enable Israelis to permanently squat in Arab homes. It’s a story that brings Amiry’s skills as writer, observer and architect together. “I think the power of the house is stronger than the power of the country,” she says. To her the trauma of losing a home is the essence of the conflict. “We abstracted [the issue] by talking about settlements, or right of return, or Jerusalem being the capital. In reality, when my grandmother or my father talk, they talk about their home.”

Culture or religion isn’t the issue, she says. It’s the loss of land or, as she writes in Golda, “the biggest real estate robbery in modern history”. There’s a palpable anger against Israelis in Golda. Things get a little testy when I ask about how people relate across cultures in this situation. First, she says, they must acknowledge what happened in 1948, the “Nakba” or catastrophe. “Somebody who believes the Palestinians have equal rights like the Israelis becomes my friend — whether they are Israeli or Jew or Christian or Australian.” Then there’s the qualification. “I don’t want to sound civilised by having Israeli friends. I don’t want to be intimidated by that. I don’t want people to judge me — who I am, what I think — by whether I talk to an Israeli or whether I have an Israeli friend. For me it’s just another kind of racism.”

Identity. For Palestinians it’s not only political, it’s existential. “In the last chapter of Golda I say I wish there will be one day in my life where I don’t remember I am Palestinian. For me this is the catastrophe — that you have to be reminded every single minute of your life.” – Chris Barton

Julian Baggini

The author says, “Every piece of the puzzle I have assembled [here] has been made by others before me.” Gee, thanks, but couldn’t you have shoved that in before page 181? Not that it isn’t illuminating to roost on the shoulders of giants and point out the sunlit uplands. But I’m not sure if making philosophy sexy for shopgirls, like a slightly more swotty Alain de Botton, is what Freedom Regained: The Possibility of Free Will is aiming for. I asked Julian Baggini this question in a Skype interview where I got to stare at a painting of him for 45 minutes. (He said he looked “too messy” to switch on the camera. Who knew philosophers cared about that kind of thing?)

“We hear a lot from scientists, and people claiming to speak for scientists, that free will has been proven to be an illusion. That is a dangerous view.”

So, why write this at all? Baggini is nobly trying to rescue the concept of free will from obliteration. “We hear a lot from scientists, and people claiming to speak for scientists, that free will has been proven to be an illusion. That is a dangerous view. If we adopt the idea that free will doesn’t exist in any sense, then what we’re going to end up with is very harmful; it robs people of any sense of agency and responsibility.”

Free will has been under attack from all directions, and a shape-shifting Baggini gives chapters to some of the culprits: the Neuroscientist, the Geneticist, the Artist, the Dissident, the Psychopath, the Addict. He provides some bouncy arguments to support his position, which, in a nutshell, is that free will is not an on-off switch. It is not something we have or don’t have; rather it is a collection of things, like roast beef, steamed carrots, fried mushrooms and braised cabbage on a plate of dinner. I think it is fair to say Baggini is not an adventurous man, in food, or elsewhere. He is a very tidy thinker though.

In one neat point he challenges the notion that for a choice to be free we must be conscious we have made it: on the contrary, he argues, artists often have no idea where their ideas come from but their creative “choices” are archetypes of freedom.

I found him less easy to like on addiction. He told me he has not personally experienced addiction or mental illness. This ought not to matter, but it does. It is hard to hear his arguments when distracted by the way he refers to addicts as “them”; when he says addicts “indulge” because they enjoy it (for many: not really); when he says addicts “don’t want to give up enough” and it is puzzling why “they” continue to “indulge their pleasure”. I know he’s trying to find a way to hand some control — and thus hope — back to addicts, but there is a danger when you write about a field outside your expertise that you come across as either priggish or lacking in empathy. (I would have liked to have been able to see into his eyes on Skype.)

Baggini said it was strange that I got the disheartening impression he sees human identity as fixed. In the book he says: “We cannot change our characters on a whim and we would not want it any other way.” Bosh to that. I have a whole bloody cast of characters which make up the jumble-sale that is me, so my idea of freedom is to choose which one of these to put on. Yes, even on a whim. In this view each moment of life, each human interaction, is an opportunity to assert one’s newly developing self. That sounds like a kind of freedom to a messed-up person like me. – Deborah Hill Cone

Jean-Christophe Rufin

It’s an impressive CV, but one can imagine that with a persona as diligent and focused as Jean-Christophe Rufin’s, you might value a little time out.

Physician, co-founder of Médecins Sans Frontières, former ambassador to Senegal, activist, second-youngest member of the French Academy, and, as if that were not enough, a novelist and twice winner of France’s highest literary accolade, the Prix Goncourt — all of this Rufin set aside for a month as, shouldering a rucksack, he took on the identity of “pilgrim” to walk the northern route of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

He took no notebook, preferring to allow the ancient Way of St James to work its magic, which is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering. Then he wrote a book, The Santiago Pilgrimage: Walking the Immortal Way. Rufin answered Metro’s questions by email.

You started out with no intention of writing a book about your journey. What, finally, convinced you to do so?

Good friends, publishers in Chamonix specialising in mountain literature, proposed that I write a novel, since I have been practising alpinism for a long time.

I wanted to help them but felt my experience of climbing was not interesting enough. They suggested Compostela. At first, I refused. But as I was coming back home, memories of the Camino rushed into my mind. They were there, waiting for me, ready to be written on a white page. My brain had selected what was important and rejected what was not.

It was time to start the pilgrimage for the second time, sitting at my desk.

You appear to relish the anonymity of being a “pilgrim”. How much of the attraction of the Camino is the opportunity to forget ourselves, put aside our carefully constructed persona for a while and become invisible, or at least transparent?

Long pilgrimages like Compostella are unique occasions to experience a life without identity or, at least, without your social and familial persona. People you meet ask no questions about your profession nor your origin. What they want to know is: where did you start the Camino? When you think about it, it’s a very philosophical question. But it is also a good way to analyse the kind of pilgrim you are: serious, dedicated to the Way for months; amateur, walking a few days to know what it is; fake if you pretend to walk but use taxis to shorten the effort.

Journeys into unfamiliar and potentially dangerous places feature in several of your novels, and, of course, your work as a physician, a diplomat and humanitarian. Is some degree of innocence, of naivety, essential in undertaking such journeys? And is this same spirit required of the true pilgrim on the Camino, as opposed to the tourist or the marathon walker?

The topic of all my books, novels as well as non-fiction, is always the experience of other cultures and civilisations by someone who is not prepared for it.

This confrontation can take place between groups, like in Brazil in the 16th century, when French chevaliers of Malta created an ephemerous colony among Indians. Or in the mind of a protagonist, like in the novel Katiba, in which a young woman is torn between the Islamic world of her mother and the European origin of her father, in the context of terrorism and civil war in Algeria. The Compostela pilgrimage is nothing but the same experience, individually and with less dramatic stakes.

You argue that the Camino can affirm pretty much any “spiritual traditions”. Is this part of its appeal nowadays? Is it the ideal ritual for post-modern people seeking an alternative to secularism that is not sectarian?

Historically, the Camino is a Christian pilgrimage, of course. But… all along its history, the pilgrimage has taken new meanings and reflected the spirit of the times. Today, it has become the expression of post-modern quests. – John Sinclair

Vivian Gornick

George Gissing’s The Odd Women explored the fate of spinsters in Victorian England. Writing about New York more than a century later in The Odd Woman and the City, why has Vivian Gornick adopted the appellation? Her voice down the line from the East Village is warm and relaxed at 80. “Women who were struggling for equal rights were called ‘new women’, ‘liberated women’, ‘free women’. But Gissing called them odd women, and that’s how I designated myself, as a woman who was not at ease with the arrangements of the world… There’ve always been people like us, but I thought he nailed it. Many women of my generation would call themselves the odd women.”

Gornick has a long history of voicing the concerns of self-declared “odd women”: she started out writing for the Village Voice in the ’70s, and in the thick of second-wave feminism, her polemic was as white-hot as anybody’s. Nearly 40 years later, it’s the gap between high ideals and messy reality that holds her interest. “You set yourself a goal about what kind of person you want to be, and then you struggle with all the internal baggage, everything that goes against the ideology, to make your peace with it.

“You always think that rational intelligence is all that’s required, but it’s the last thing that’s required. It’s some emotional integrity that’s required.”

Struggle gives every good memoir its narrative drive, as Gornick showed in Fierce Attachments, her blazingly lucid account of the difficult relationship she had with her mother. In The Situation and The Story, her how-to guide to writing, she underlined the importance — and the difficulty — of choosing the right ‘self’ to tell a personal story: the cogent, illuminating self, as opposed to the dull, contradictory selves that live in all of us.

It’s required reading on many MFA programmes across the States, programmes at which Gornick has taught. For a writer brought up in the Bronx, the experience of living in small college towns underlined how essential New York is to her imagination. “Manhattan was the centre of the world for all of us who grew up in the Bronx, or Brooklyn or Staten Island or Queens. We longed to come to the centre of the city, and that becomes a kind of template for living… The thing that is so intolerable for somebody like me, are the empty streets. The good small city where nobody is on the street.”

Gornick needs a city that rewards her fearlessness and curiosity. It’s “the boldness of gesture and expression everywhere” that captivates her about New York, she writes, but her own boldness is as beguiling. In The Odd Woman and the City, she’s always stopping people on the street: asking a young girl if her beautiful shoes are comfortable, interrupting a man yelling at nobody in particular in order to correct his grammar. “In New York people on the street always start talking to each other,” she tells me. “My mother was like that. I was made for it.”

Getting older has pulled her into a deeper engagement with the city. One of the more arresting lines in her new book is, “Turning 60 was like being told I had six months to live.” Why so? “It’s a moment in life when I was suddenly brought up short by the realisation that I wasn’t living in the present a lot of the time. I spent a lot of time daydreaming, imagining an ideal past, or an ideal future…

“And I saw then, that this was a moment in life when I had to change, when I had to be more present, and the streets of the city actually helped me. I concentrated a lot more on what was around me, and it did centre me. When you’re young, you think you have endless amounts of time to account for yourself, but when I hit 60 I thought, there’s no more time to imagine accounting for myself, I have to start doing it now.” – Noelle McCarthy

Auckland Writers Festival, May 10-15. See writersfestival.co.nz for the programme.

Read more: A guide to the Auckland Writers Festival: Part one

Illustration: Lauren Marriott exclusively for Metro.