Aug 10, 2016 Art

Auckland Art Gallery’s exhibition of art from South America is politically charged and perfectly timed.

In 1987, the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar made an artwork for New York’s Times Square. On a screen above an armed forces recruitment centre, A Logo for America showed the outline of the United States with the words, “This is Not America”, then the Stars and Stripes with the words, “This is Not America’s Flag”.

Jaar’s point was that the name of an entire continent had been hijacked by a single nation — the US. In the beating heart of Western capitalism, his work reminded New Yorkers that south of the border is another America, one with its own rich culture, complicated politics and history of resisting US imperialism.

Jaar’s seminal piece opens Space to Dream: Recent Art from South America, the Auckland Art Gallery’s outstanding winter exhibition. It’s pretty rare to experience a show at a public institution as a call to political action. But that is exactly what Space to Dream feels like.

Of course, it’s many other things, too. It’s a solid, considered art historical survey. It’s also a transpacific proposition: a speculative statement about the possible connections between New Zealand and a continent on the far side of the same ocean. The danger of this is it becomes a kind of economic icebreaker — exhibitions often act as the aperitifs of trade conversations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Air New Zealand are listed as supporting partners for Space to Dream; then there’s the recent news that New Zealand is opening an embassy in Bogotá.

But this is no expo moment. Curated by Zara Stanhope and Beatriz Bustos Oyanedel, it is politically charged and perfectly timed. Even a year ago, works like Jaar’s may have seemed dated — interesting, sure, but belonging to a long-past period of activist art. But right now, in a post-GFC, pre-Donald Trump-as-

President world, the destructive South American legacies of the US, the Peróns, the Pinochets, the Noriegas and the Escobars have razor-sharp relevance. And so do the artists who stood up to them.

Space to Dream is proof that resistance to oppression, dictatorship, brutality and fear can produce beautiful work.

Much of Space to Dream’s cleverness is embedded in its title. At first glance, it’s an unpromising, magical realist cliché. But that’s if you read it as a place — “a space to dream” — rather than as a continuum of conceptual possibility — “from space to dream”. The work contained within the show slides along this spectrum, between two seemingly opposite forces of cultural disruption: interventions in architectural and civic space on the one hand, and a sort of surrealist sensuality on the other.

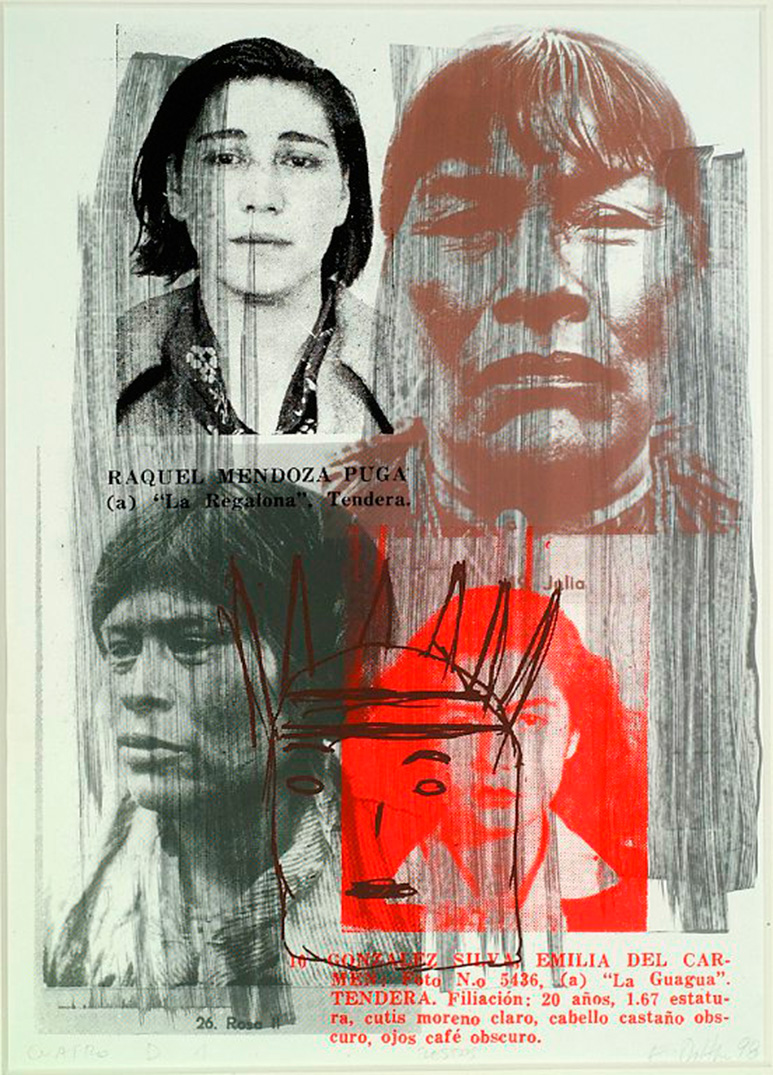

Despite this, the first half of the exhibition is pretty dry: mainly wall-based works, heavy on photography and video, with plenty of text to chomp through. There are some highlights, though. Eugenio Dittborn’s prints, which simultaneously draw upon pop culture, police records and Chile’s history of missing persons, are one example. The Colombian Juan Fernando Herrán’s large-scale photographs of Medellín’s strange, vertical relationship with space are also impressive — potent records of a landscape and city still best known, internationally, for their central role in Pablo Escobar’s cocaine empire.

The second half of the exhibition has a completely different physical register — a shift that arrives dramatically with Ernesto Neto’s Just like drops in time, nothing, a huge sculpture made of stretchy fabric pendulously filled with spices, including turmeric and cloves. The following space brings together two of the great South American artists, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica. Both were at their creative heights in the 60s, when they developed countercultural, hippyish practices that embraced performance, costume and the political possibilities of sensual encounter.

This vaguely hallucinogenic mood runs right through the Robertson Galleries, which are framed at each end by the sound of water — Joaquín Sánchez’s video Línea de agua (Line of Water) at one, actual water in Máximo Corvalán-Pincheira’s Proyecto ADN (DNA Project) at the other.

Maria Nepomuceno’s Grande Boca (Big Mouth), continues the sensory overload: an enormous, bright red-and-orange sculpture with a massive beaded tongue that spills across the floor. And an excellent group of video works tucked away in a darkened room includes Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León’s bad-trip stop-motion animation Los Andes.

Los Andes, though monstrously strange, doesn’t shy away from the legacies of colonialism and capitalism in South America, and this is ultimately where Space to Dream’s most powerful work resides. Like Jaar, plenty of the artists attack the hegemonic impact of North American culture on their art and on the politics of their respective nations. But several also highlight the specific atrocities of their own governments. There is, for example, a superb collection of works by the Chilean collective CADA, who actively protested Pinochet’s oppressions. And there are photos of poetic-political performances by the Brazilian Paulo Bruscky, who was imprisoned three times and whose statement that “being an artist is already a political attitude” acts as a summation of the entire show.

Several recent works, like Patrick Hamilton’s Intersecciones (Intersections), which simultaneously references South American abstraction and the impact of copper mining on Chile, examine the last throes of neoliberalism. And boy, is it thrashing violently in Latin America and the Caribbean at the moment.

Venezuela’s economy is imploding with the oil-price collapse. Global banks and the US government are hanging Puerto Rico out to dry. Brazil is hosting the Olympics despite its poisoned waterways, its horrendous inequality and its unfolding political coup. And god knows how the Mexicans will react if Trump actually wins the presidency and insists they pay for his ridiculous wall.

It’s easy to laugh. Except we’ve been laughing ever since this nightmare started, and it’s getting more likely by the day. If Trump wins, the one thing we can be sure of is that neoliberalism will be well and truly dead. But whatever takes its place will be far worse, and that’s when we’ll need our artists more than ever. Space to Dream is proof that resistance to oppression, dictatorship, brutality and fear can produce beautiful, important work — and occasionally, genuine social and political change too.

Space to Dream, Auckland Art Gallery until Sunday 18 September 2016. aucklandartgallery.com