Oct 10, 2019 Books

Traditional methods of reaching voters have been left looking antiquated by the sudden rise of targeted digital communications.

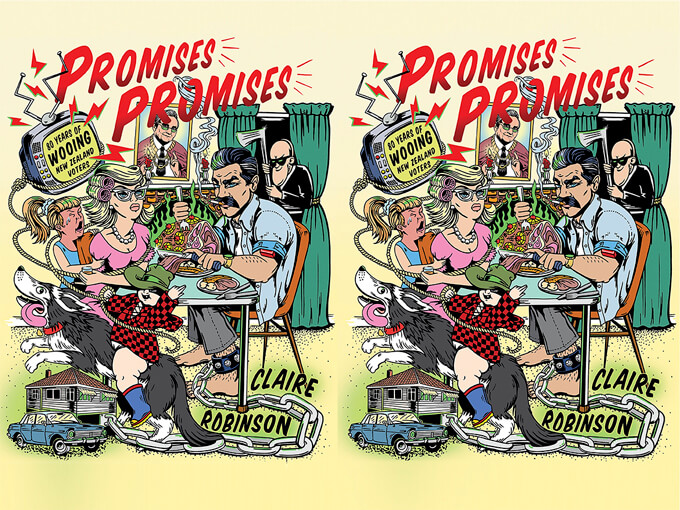

Reading Promises Promises: 80 Years of Wooing New Zealand Voters, I found it impossible not to wonder whether Dr Claire Robinson has expertly documented an era of mass political communication that is coming to an end in the internet age.

It is a “visual history of New Zealand politics” told primarily through striking reproductions of newspaper advertisements, flyers, manifestos, pamphlets and posters, some stills from television broadcasts, and a scattering of very recent internet ads.

Political advertising speaks through metaphor, and New Zealand parties have developed a particular dialect in making their pitches to the electorate: wellbeing is depicted as families on beaches, for example; economic progress in the 80s was shown by pitches in corporate boardrooms, and in the 2000s by hard hats and hi-vis.

Even seemingly concrete issues are often little more than symbolic shorthand. A National campaign booklet in 1949 lambasted the Labour government for spending taxpayer money on “super-duper cars for Ministers” — a signifier for extravagance and aloofness that has persisted for seven decades without any noticeable diminution in the quality of Crown transport once outraged oppositions reach government.

Visual language can be decoded, but it cannot be reasoned or argued with, or interrogated and made to give up the truth. The same goes for graphs and the ubiquitous use of statistics in isolation. A 1954 National pamphlet proclaims, among a raft of figures about increased production of nylon stockings, cement and cigarettes (!), that “statistics culled at random tell a story of prosperity that nothing can gainsay”. In 2017, we have the Treasury’s wellbeing measures, from the 1970s we had OECD rankings, and in 1951, we had boasts about the number of lamb carcasses eaten by New Zealanders each year.

Political-party advertising, Robinson explains, expresses and reinforces a dominant political culture. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, that culture is unmistakably centred on the aspirations of middle-class, Pakeha nuclear families, with men as breadwinners and women as nurturers. Since 1938, the first Labour-versus-National general election, both major parties have focused on economic growth to fuel progress and prosperity, and consumption to improve living standards. Happy workers, young home buyers, and families sharing meals (or playing on iPods) dominate through to the present day.

While non-directionally broadcast in newspapers, in letterboxes and on terrestrial television, these messages are pitched at the frequency of the “median voter” — the semi-mythic person in the exact middle of the political spectrum, with equal numbers to his (and throughout most of the 20th century it was his) left and right, ready to cast the decisive vote in a majority-rules democratic system.

Robinson approached her project by arranging and re-arranging hundreds of images like collage for months before patterns emerged. It may not be surprising that being stuck in the graphic landscape of pleasant middle-class suburbia and small New Zealand towns over a period of 80 years spawned a sense of nihilism in the author. Like the children who could be imagined sitting inside the picturesque but bland housing developments of National and Labour ads of the 1950s and 1960s, Robinson cannot help thinking about what is beyond.

The absences in Promises Promises’ catalogue of happy white couples haunt Robinson like a phantom limb — she returns frequently to the under-representation of Maori parties in advertising and in Parliament, the inability of third candidates to crack the FPP duopoly, and democratic failures such as inaction on climate change, where meaningful policy change runs headlong into the roadblock of the totemic values of growth and economic progress.

There is a sense of urgent need to break the paralysis in New Zealand politics she sees reflected in her static images. But her proposed fix only seems like another window into the past. Possibly inevitably for an academic specialising in political advertising, she wants to increase the state-funded Broadcast Allocation for radio and TV ads for “Maori and minority parties”.

It’s a strange prescription given the very recent failures of hugely resourced eccentric millionaires’ parties Internet-Mana, the Conservatives and TOP.

It is also a solution for a different age. The televised leaders’ statements that traditionally kicked off the election campaign were canned by TVNZ after the 2014 election because of poor ratings. It’s notable that many of these statements took the form of real or staged “town hall” meetings. The very notion of a common “town hall” for political mass communication is disappearing, with the advent of social media and targeted communications to sidestep — or more effectively reach — the median voter.

This shift has been sudden. When Barack Obama’s social-media maestro, Teddy Goff, visited New Zealand in 2013 to proselytise about Facebook, Twitter and the power of direct engagement, no one in Prime Minister John Key’s office even bothered to reply to his offer to hold a seminar for Beehive staff. The internet, and social media in particular, was regarded with suspicion and hostility on the ninth floor.

A Young Nat temping at Parliament at the time, Sean Topham, got in touch with Goff privately and held a hastily arranged session for some (including me) working in the building to attend. Six years later, Topham is credited with getting Scott Morrison’s unlikely Australian 2019 election win over the line via an expert social-media campaign.

Even without the shady data-sharing practices of Cambridge Analytica and its ilk, Facebook’s affordability and ability to target based on interests and demographics make traditional methods for reaching into the electorate’s niches look as antiquated as the bold letterpress poster Robinson reproduces from the 1853 election.

Recent National Facebook ads have attacked the government’s proposed charges on fuel-inefficient vehicles, with micro-targeted ads differentiated down to the level of individual cars for which different readers may be in the market.

This may seem like good news for the afflictions Robinson diagnoses. Greater targeting is not only happening along explicitly consumer lines (brand of car as democratic identity), but the non-mainstream ideas that thrive in this new world are just as likely to be anti-vaccination or climate-denial memes as power-sharing with Maori.

Even worse, the lack of a shared — if unrepresentative — political culture in the United States thanks to partisan cable media, social-media isolationism and the ever-present threat of fake news seems to have led to more polarisation than ever. Robinson will have an interesting sequel to write in 10 years’ time.

Promises Promises:

80 Years of Wooing

New Zealand Voters

Claire Robinson

Massey University Press, $59.99

This piece originally appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Old tricks”.